Herrera is part of a generation of queer artists tasked with chronicling a community of shifting realities.

May 15 2015 4:00 AM EST

May 26 2023 2:10 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

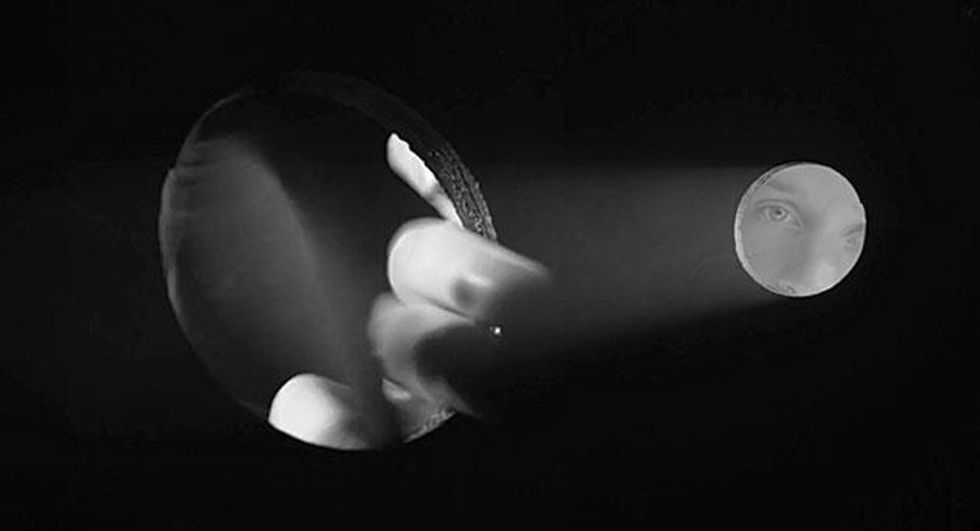

Those familiar with certain gay party scenes on either coast have probably already run across the work of filmmaker Leo Herrera, whether it was projected onto the wall at a circuit party or shared breathlessly across Facebook during Pride season. His three-to-ten-minute clips and trippy party visuals are catnip for a small subset of gay men: the new generation of club freaks, PrEP-equipped HIV/AIDS activists, sex-positive sluts, and LGBT history buffs. Often commissioned by nightlife promoters and queer film festivals, many of his short clips swirl around visual effects of pulsing, symmetric genital kaleidoscopes, or full-body capes that swallow the bodies wearing them in slow motion (and are created by Herrera's fashion-designer brother Allan for pieces like Leo's Frameline Film Festival 2011 trailer).

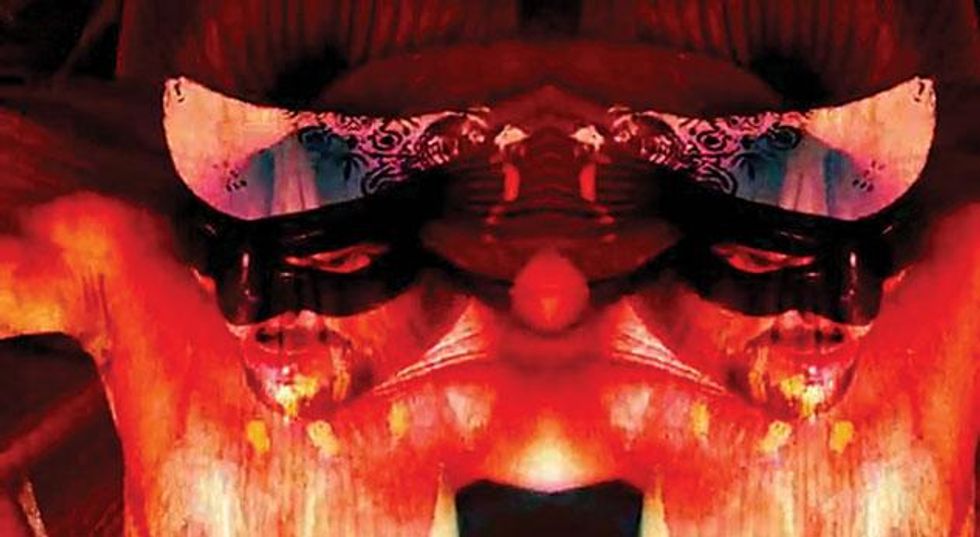

Rosebuds of floral and anatomic persuasions fade into one another, as in his visuals reel for New York's 2012 Black Party. In another experimental piece, eggs cracked into an aquarium full of boiling water yield a jungle of undulating texture.

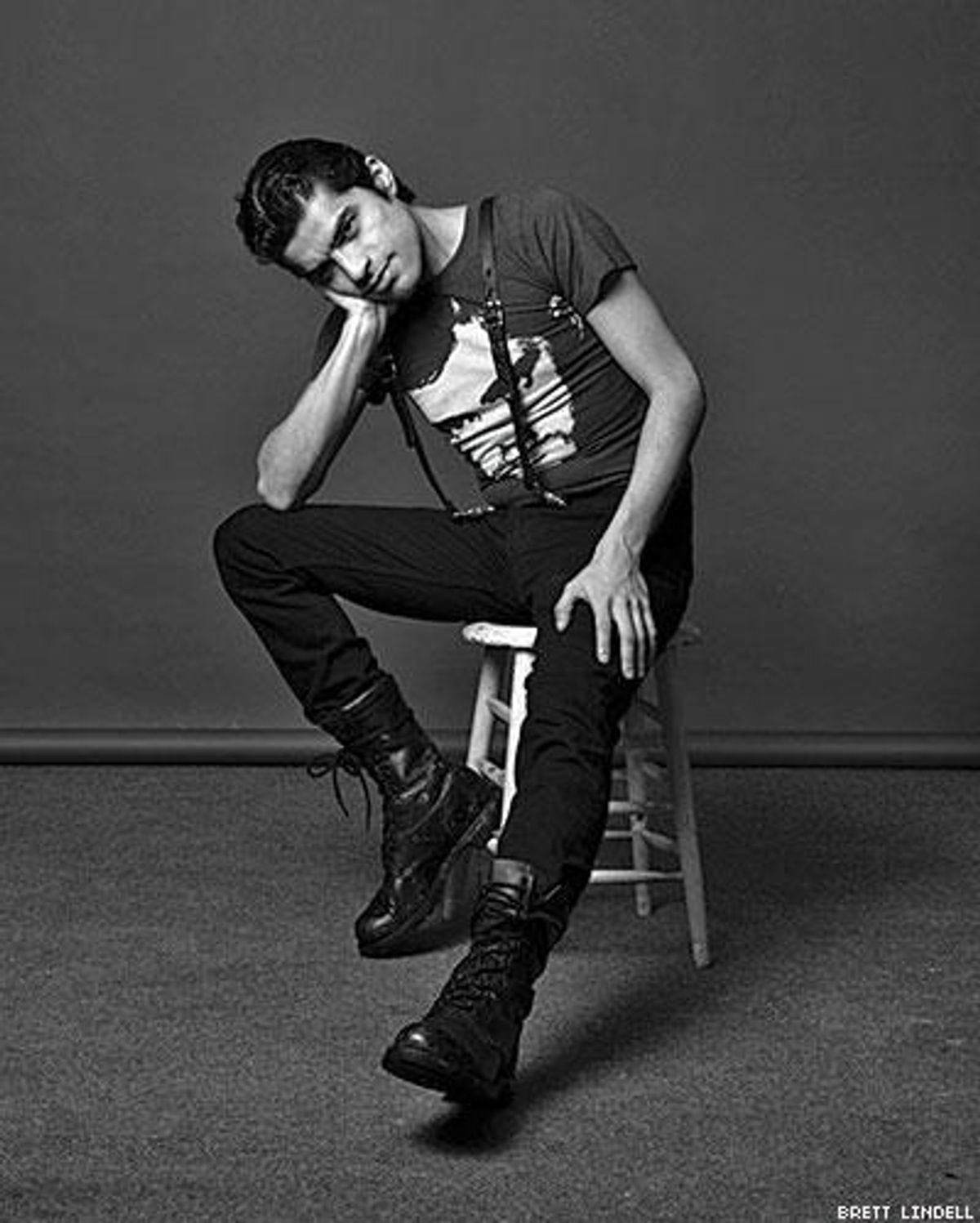

Full-bodied human beings also exist in Herrera's filmic language. His shorts have featured studly unknowns and stars like rapper Cazwell, party promoter Ladyfag, the legendary Amanda Lepore, and Joey Arias. But his penchant for compelling abstracts is telling. It speaks to Herrera's motivation as a filmmaker, which is the hunt for something that has long been tamped down, hidden from the public and brought out only in dark, throbbing undergrounds. It is anti-assimilationist and has very little to do with the forces that call for mirror-image marriage laws for queers. Herrera's quest is to find the essence of that which sets gay men apart from the straight world, and even from other queers.

He finds much of his inspiration in a certain kind of #ThrowbackThursday photo fare: Examine that coy tilt of your buddy's 8-year-old head, the flick of his wrist captured for posterity by an earnest parent with a Kodak. These are the undeniable markings of a gay boy who will one day become a gay man. "What is that?" Herrera asks of this shared affect. For the filmmaker, these arch social-media moments are not only the homosexual body language but also clues to what he refers to as "the unmistakable softness," a gay male culture that crosses geographic borders and calendar years, one that long ago went into hiding due to the slings and arrows of heterosexist misfortune. He calls his quest for inspiration in his films "talking to the gayngels," a channeling of queer voices from days past.

The 33-year-old filmmaker's Radical Faerie-like devotion to this tie that binds gay men gives a delicate cinematic caress to even the hardest-bodied of his peers, lending poetics to throbbing dance floor shots, or a Wakefield Poole-esque beauty to three-way scenes. A more literal manifestation can be found in the "Gayngel" series that he has begun with his brother. In its opening chapter, the titular character strides underneath the Dick Dock, Provincetown's seaside cruising grounds, in a high-collared gray cape and sequined lucha libre-inspired mask. The fraternal duo plan on making more of these shorts, each with a different Gayngel look inspired by the shoot location. Leo's metaphoric advisors are brought to life in their cruise through history, a reflection of the auteur's desire to educate his peers on what came before.

His work has been influenced by the hours he's spent at LGBT history museums and archives. Through them he has learned about history's ability to loop--the connection between today's alt queer performers and Berlin's 1920s cabaret scene, as an example.

His 2014 release, "3 Eras of Gay Sex in 3 Minutes," is an art house look at the history of cruising. There is no overarching menace of HIV/AIDS in the short film. Rather it's a redolent look at pointed male courtship. A timeless babe in a leather jacket (played by Rikki Crowley, a.k.a. hip-hop artist Rica Shay) carves a peephole in the wall, and his gaze falls back through time to a pre-Stonewall-era sailor dropping a napkin scrawled with rendezvous instructions onto a bar table. In another scene, a denim-cutoff-clad boy and a leather daddy find each other above San Francisco's Baker Beach, a nod to modern-day hookup apps. The short takes are layered with voice-overs by Walt Whitman, Truman Capote, and puppy fetish master Pup Boss Jyan. It makes for a historically rich effect so dense that one wants to replay the film's three minutes over and over. Herrera has no plans to make movies with longer run times. He has too much respect for his YouTube generation's penchant for consuming media on smartphones in the short intervals between subway stops, or while waiting for a friend in a bar. From viral-ready shorts to mood-setting circuit party visuals, Herrera's works are functional, meant to be useful to the 10 percent of gay men who Herrera estimates "get" his mix of history and sex.

"We don't get to have our own culture in terms of visibility," he says. "So we're borrowing, and we've always been borrowing." It's hard to miss the connection between abstract visuals of whirling genitals and the hallucinatory 1960s "be-in" party visuals; both were created to set the mood for members of the counterculture. But when it comes to his usage of other cultures, he has faced some pushback, most notoriously against his 2014 promo trailer for New York City's historic annual circuit soiree, the Black Party. The clip does not feature the writhing torsos or exhibitionist blowjobs the gathering is best known for. Instead, viewers see religiously charged footage from India. A dead holy man's body is administered postmortem rites, and a funeral pyre is prepared. Unadorned and graphic, the trailer intends to juxtapose the weighted Hindu rituals with the Black Party's morbid history of HIV/AIDS death and displacement. Still, age-old traditions are being used to advertise an expensive circuit party. The dissonance, at least, is intentional, meant to elevate gay ritual and indicative of the filmmaker's respect for nightlife's role in gay culture.

Herrera is part of a generation of queer artists tasked with chronicling a community of shifting realities. Whereas his works heretofore (including 2013's masterful "The Fortune Teller," which racked up 50,000 views the week it was released during San Francisco Pride) focused on honoring gay forefathers and the struggles that came before, Herrera says future projects will turn the gaze forward. He wants to address young gays over topics that their generation will be among the first to face -- a list that most definitely includes PrEP and the consequences the medication will have on the gay community, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS stigma. He's also announced an upcoming project with artist Jordan Eagles that will explore the recently lifted ban against gay men donating blood.

"To be proud, truly proud of something," he says. "You have to look back on the losses that the success of the present are measured by. You have to look at the love that binds and the passion that propels those successes and you have to allow yourself to feel happy and even lustful for more, not just for yourself, but others." It speaks to his mandate: Listen to the gayngels, but also elevate those who will join their ranks some day.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered