In 1988 rocker Melissa Etheridge demanded, “Somebody bring me some water!” That Grammy-nominated song fueled a fire in her and her fans. “Can’t you see I’m burning alive?” she pleaded in song to a lover who’d spurned her with another. Now, 36 years later, she’s invoked another conflagration in song. This time she belts about the kind of inner spark that ignites change in the anthem “Burning Woman,” written for and performed live for the first time at a concert for the women of the Topeka Correctional Facility on the grounds of the institution in Etheridge’s home state of Kansas. Like Johnny Cash's famous performance for those incarcerated at Leavenworth, a show the Grammy-winner was aware of as a girl growing up nearby, Etheridge delivers the women at the facility an escape from their day-to-day and a sense of community and healing through music. That concert now exists for posterity in a live album and the two-part docuseries Melissa Etheridge: I’m Not BrokenI’m Not Broken on Paramount+.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

Etheridge came out as a lesbian publicly, boldly, in 1993 when doing so was still considered a career killer, and says she feels like a “proud mother” of today’s unabashed queer artists. The lyrics from her breakout hit, “Bring Me Some Water,” from her eponymous first album, are as immediate today as when the song first hit the airwaves 36 years ago. She brought the water and quenched a thirst for those who bore witness to her show at the Topeka Correctional Facility.

But for this mother of rock and roll who inspired a generation of queer women to declare, “Yes, I Am,” the concert at the correctional facility, which coincided with letter writing and conversations with a handful of the residents all touched by drug and/or alcohol addiction, became an exchange of hope born of grief. Planted onstage in a black cowboy hat emblazoned with a steer, the Kansas native speaks frankly with her audience about losing her 21-year-old son, Beckett Cypheridge, to fentanyl and opioid addiction in 2020. With her 2023 memoir, Talking to My Angels, the limited engagement Broadway show about her life, Melissa Etheridge: My Window (2023), and a current tour that includes dates with Jewel and the Indigo Girls, I’m Not Broken draws a throughline from past to present with empathy at the core.

“I know that my art has healed me just year after year after year. It keeps healing me. Every time I’m onstage [to experience] an energy that bypasses the brain that goes straight to the soul and the heart — oh, my gosh,” Etheridge tells The Advocate. “I’m just so grateful and always hope that my music can do that for people. And watching the documentary and seeing it, seeing their faces [the women at the correctional facility], it just made me so happy.”

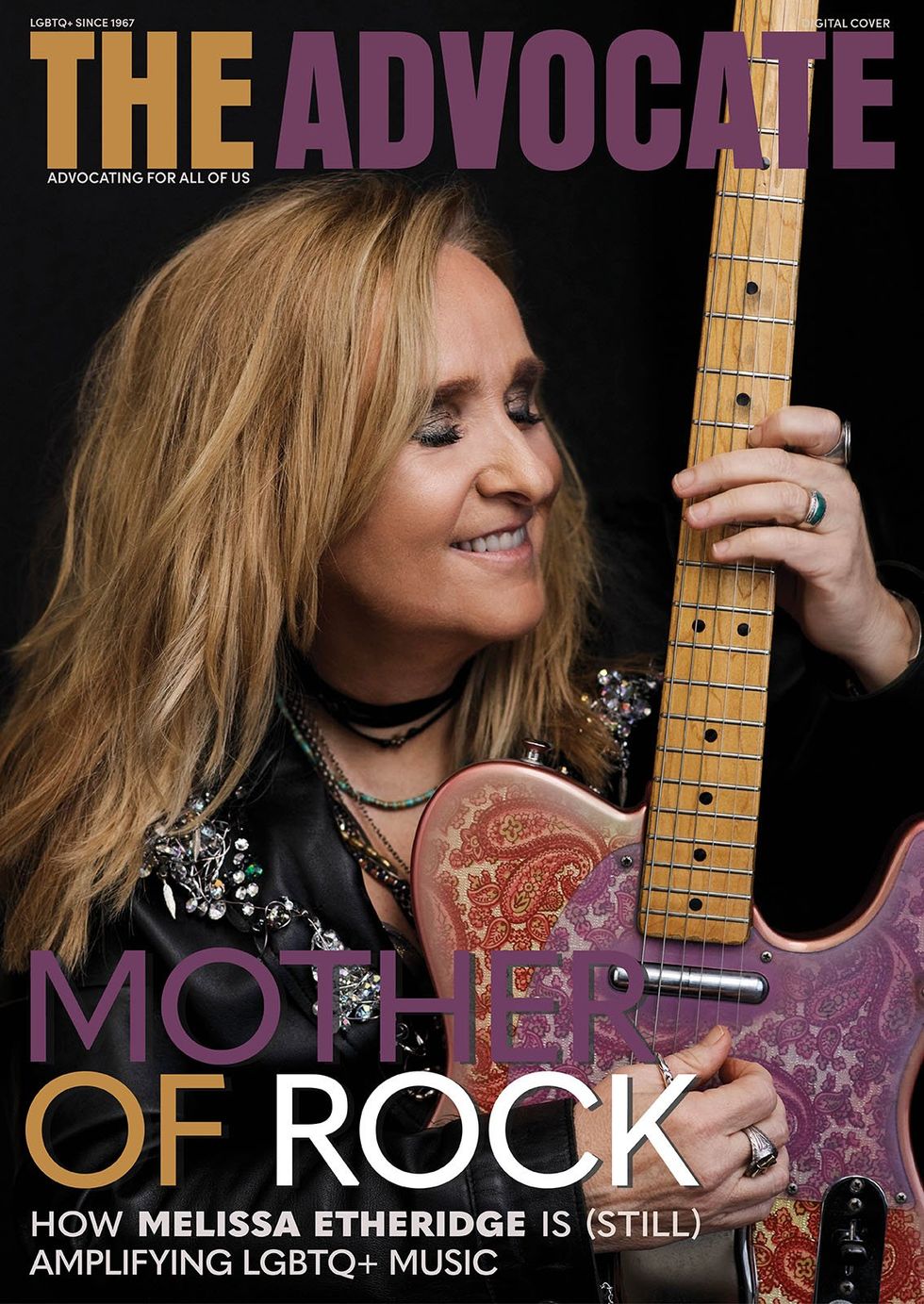

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

The I’m Not Broken documentary kicks in with a snippet of Etheridge performing “I’m the Only One” from her 1993 album Yes I Am. The women of the Topeka Correctional Facility sway and sing along to the declarative hit. At various times throughout the concert, Etheridge addresses those who may not be familiar with her and invites them in. Yet even for those concertgoers who don’t sing along verbatim with hits like “I Want to Come Over,” Etheridge is real and approachable in a way that they know her essence and give back to her with open hearts. She introduces “The Shadow of a Black Crow” from her 2012 album 4th Street Feeling by sharing Beckett’s story. They respond with a tear-jerking gesture of empathy.

“They were all so kind, and they all held up little heart signs with their hands. And then I said, ‘I would give anything for my son to just be in prison and not dead.’ And that’s true. … There's always hope. There’s always a different choice to be made every day,” Etheridge says. “And I also saw that I can't save anybody. I couldn't save my son. I can't save them. I can just maybe shine a light to help them on their path.”

The performance at the Topeka Correctional Facility was far from Etheridge’s first at a prison. She performed at state and federal penitentiaries as a teen in the ’70s. So the idea of a concert for the women in Topeka was a return of sorts. Once the plan to shoot a documentary and concert was in place, a common narrative emerged.

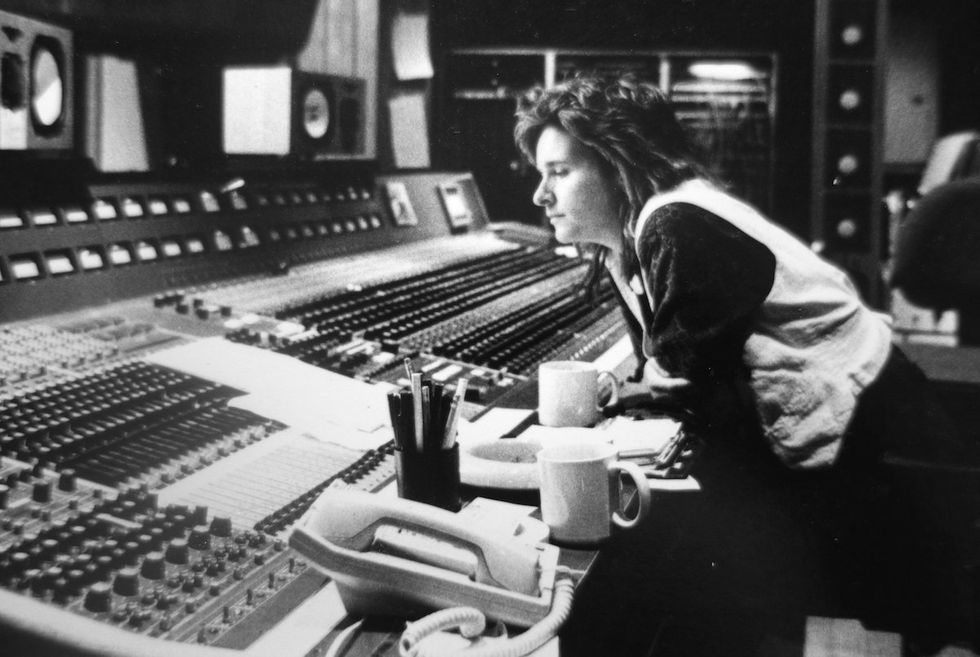

Melissa Etheridge early in her career Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge early in her career Courtesy Primary Wave

“It got closer and closer to sending letters … the letters were really the first thing, and it sort of really became clear and obvious what we were going to focus on, because it was glaring how each of these women had issues with drugs,” Etheridge says. “Those issues came from early trauma in all different ways, but trauma nonetheless. It was very hard to read their stories. And some of them just wrote pages and pages, and so it really affected them. It was quite moving and intense for me.”

A month after losing Beckett in June of 2020, Etheridge launched the Etheridge Foundation to provide support for those facing substance use issues. Her foundation supports research for new plant-based medicine and psychedelic treatments for opioid use disorder, the website says.

“I believe that this [addiction] can be understood better, and that help through different options other than [current] options are being researched. That's part of the other foundation,” she says. “And we are looking for new ways to help people that do not respond to the 12-step program.”

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Advocacy is woven into Etheridge’s life story. She came out at the Triangle Ball, part of President Bill Clinton’s inauguration celebration, and she’s fought for causes including LGBTQ+ rights and the environment. She won an Academy Award for Best Original Song for “I Need to Wake Up,” which she wrote for Al Gore’s clarion call for the environment, An Inconvenient Truth. Though attitudes about people who struggle with substance use are slow to change, Etheridge believes in a path forward.

“Stigma is really hard to get around. And slowly I see that changing — just other things that I’ve advocated for in my life that I've seen change,” Etheridge says.

“When I first came out, the thought of gay marriage was like a joke. It was impossible. And here I am, gay-married, and my daughter’s about to get gay-married,” she says proudly of her 24-year-old daughter, Bailey Cypheridge, who announced her engagement this June.

Etheridge is Cypheridge’s mother and a mother figure to the women who sent her letters in the I’m Not Broken documentary. But she is also one of the mother figures for lesbian and queer musicians along with k.d. lang and Amy Ray and Emily Saliers of the Indigo Girls. In a year when pop supernovas like Chappell Roan and Reneé Rapp have proudly proclaimed themselves as lesbians, Etheridge is still rocking out on stages throughout the country, most recently with the Indigo Girls, shows that she joked “might be a lesbian experience that's not really happened before, and we might move the seismic needle.” With Etheridge out on the road as vibrant as ever, she's not so much passing the torch to those up-and-coming queer artists as sharing it.

“This is exactly what I hoped for when I came out, when I stepped out and said I was a big lesbian — that an artist can not only come out later after they’ve made it, but can just come onto the scene and be gay from the get-go,” Etheridge says. “That’s one of their many crayons in their crayon box. They’re gay, OK, that thrills me. Do you enjoy the music? Yes. ... The music still stands for itself. I always believed that good music just triumphs all that. … So I feel like a proud mother. Really. I do.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with addiction, SAMHSA's National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year service for those facing mental and/or substance use disorders, and can help locate treatment near you.

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave  Melissa Etheridge early in her career Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge early in her career Courtesy Primary Wave  Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Melissa Etheridge Courtesy Primary Wave

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes