Today is the 30th anniversary of the star's untimely passing.

Updated

November 17 2015 5:28 AM ESTBy continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Today is the 30th anniversary of the star's untimely passing.

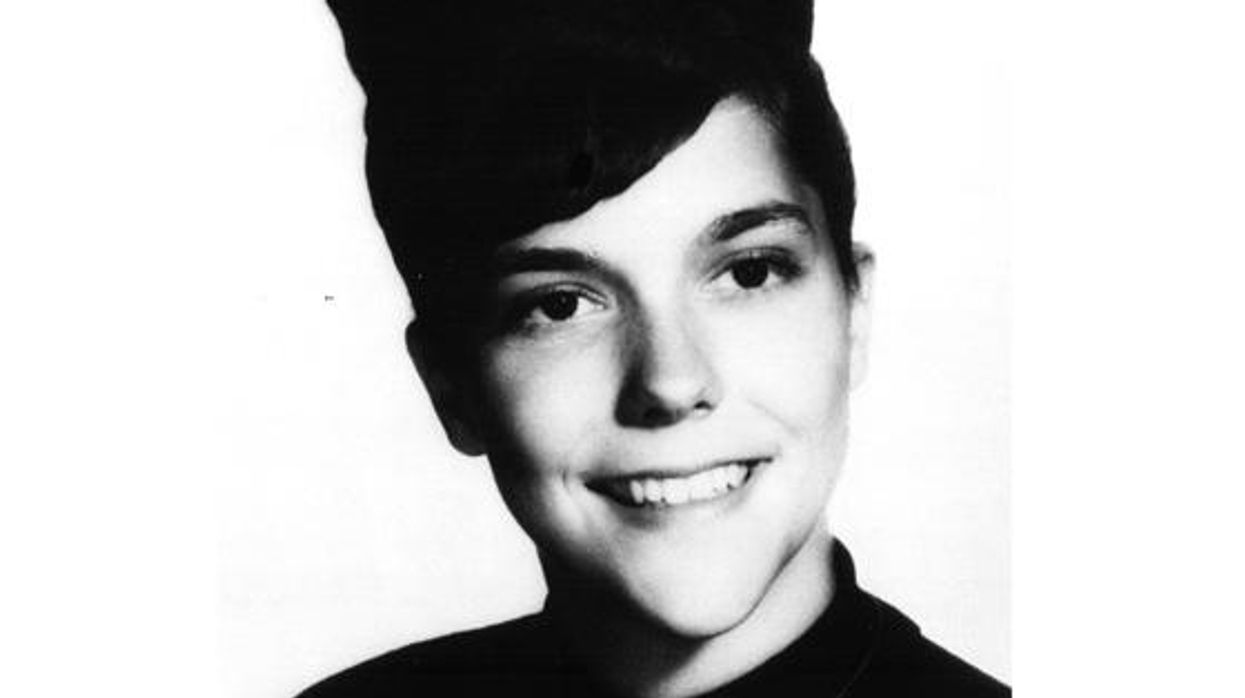

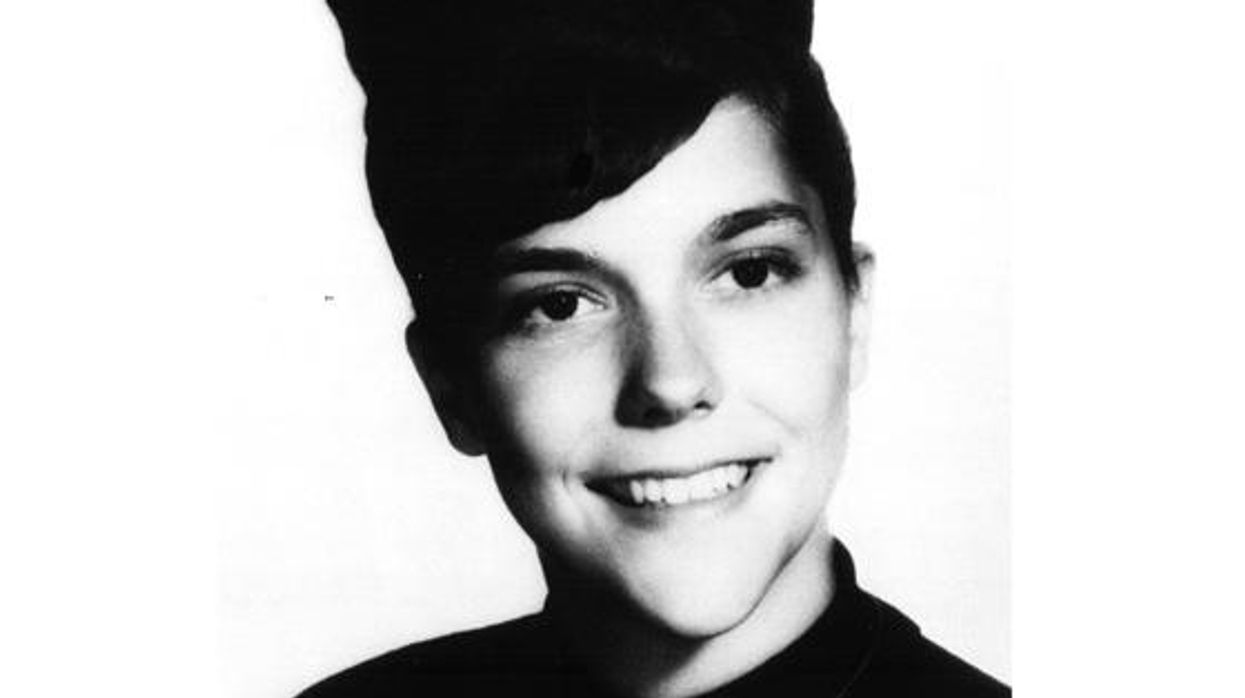

February 4, 1983: The anorexia-related death of 32-year-old Karen Carpenter sent shock waves throughout the music industry and around the world. On this, the 30th anniversary of her untimely passing, Randy Schmidt, the author of the acclaimed best-selling biography Little Girl Blue: The Life of Karen Carpenter, examines the legacy of the extraordinary singer with the heartbreaking voice and her enduring impact on other musicians and LGBT fans.

"Do me one favor. Do not do disco!" This was Richard Carpenter's only commandment to sister Karen as she embarked on a solo recording career in the spring of 1979. But disco was exactly what this velvety-voiced queen of unrequited-love songs had in mind.

"I love Donna Summer," she told producer Phil Ramone upon arrival at his New York City studios. Summer's "Hot Stuff" was her favorite song at the time. "I'd give anything if we could do a song like that!" The girl who crooned "We've Only Just Begun," the default wedding song for an entire generation, had grown up. Or at least she was trying.

With a repertoire of classic recordings like "Rainy Days and Mondays," "Superstar," "Goodbye to Love," and "Top of the World," the Carpenters have gone down in history as the top-selling American musical act of the 1970s. Theirs was a matchless combination of Karen's rich, mournful, smoky alto perfectly ensconced by Richard's brilliant compositions and arrangements in a sweet swell of aural lushness.

The duo's impressive string of 16 consecutive top 20 hits began in the summer of 1970 with "Close to You" and continued through "There's a Kind of Hush" in 1976. The hits would likely have continued, but that lovely, inimitable voice -- the muse for Richard's genius -- was silenced on February 4, 1983. At only 32 years of age, Karen Carpenter died of heart failure. She succumbed to a seven-year battle with anorexia nervosa and became the proverbial poster child for the mysterious eating disorder.

Admired in her heyday by the likes of John Lennon, Barbra Streisand, and Elvis Presley, Karen has since found her rightful home alongside those and other timeless vocalists like Frank Sinatra, Nat "King" Cole, and Ella Fitzgerald (with whom she duetted during a Carpenters television special in 1980). She is regarded as one of the finest female singers of the past century, and her legacy lives on in the music of those she's inspired. Karen put her musical stamp on a range of artists who cite her as an influential force: k.d. lang, Lea Salonga, Sandi Patty, Jann Arden, Shania Twain, Sonic Youth, and even Madonna.

Part of the legacy exists in the campy aspects of this purveyor of "polite plastic pop" (as one reviewer dubbed the Carpenters' music in their prime). In 1987 little-known filmmaker Todd Haynes attempted to tell Karen's story with a cast of Barbie-type dolls in Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, a 43-minute film shot against a backdrop of miniature interiors. Banned from distribution due to legal issues with music rights, Superstar quickly gained a cult following. Two years later came The Karen Carpenter Story, a cliched made-for-TV biopic executive produced by Richard Carpenter himself. The highest-rated TV movie the CBS network had licensed in five years, it prompted a sweeping renaissance in appreciation for the duo's music. These films, a (not quite) tell-all "authorized" biography, a tribute album by well-meaning alt-rockers, and bizarre (true) stories of Richard marrying his first cousin and Karen's corpse having been exhumed and relocated have added to our fascination with this unlikely icon.

In the pantheon of gay icons, Karen Carpenter may not be seated at Judy's right hand, but she's closer than you think. Our divas come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. And some aren't divas at all. That was the case with Karen. And perhaps it is the anti-diva aspect we find appealing. Karen was addicted to needlepoint, and her favorite drink was iced tea. She loved Disneyland and collected Mickey Mouse memorabilia. She adored Phyllis Diller, Carol Burnett, and reruns of I Love Lucy. She enjoyed shopping with friends in Beverly Hills but was at home bargain-shopping down at the neighborhood Gemco store. Most of all, Karen longed for normality. She wanted to find the love of her life, have children, and live happily ever inside a white picket fence. In hindsight, the lyrics of "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina," recorded by Karen in 1977, become hauntingly autobiographical:

And as for fortune and as for fame

I never invited them in

Though it seemed to the world they were all I desired

They are illusions

They're not the solutions they promised to be

The answer was here all the time.

The girl next door from Downey, Calif., by way of New Haven, Conn., Karen was an awkward tomboy who loved all things baseball. She lived in the shadow of her older brother, the obvious favorite of mom Agnes. Her father, Harold, rarely spoke and was often shushed. Richard was the family's musical prodigy, being groomed to be the next Liberace.

Like mom, Karen idolized Richard and took on many of his interests, with music becoming their shared passion. She took up drums at Downey High, becoming the school's first female drummer. It was at the age of 16 that the voice surfaced. That deep, resonant Karen Carpenter alto was husky and rough around the edges, but it was there. It was her unusual combo of singing and drumming that grabbed the music world's attention just a few years later when the sibling duo debuted on Herb Alpert's A&M Records label.

In opposition to the supporting role she was given within the confines of the Carpenter family enclave, the rest of the world realized Karen was clearly the star of this fresh-faced, burgeoning musical act. Against her will, though, she was soon weaned from her singing drummer safe haven and pushed into the center-stage spotlight to front the group.

When Karen's eating disorder surfaced during the summer of 1975, collective gasps were audible from audiences when she took the stage. Fans grew concerned and knew something was terribly wrong. Some assumed she had cancer. By September, Karen was down to 91 pounds. Mammoth tours of Europe and Japan were canceled and she was hospitalized for mental and physical exhaustion. Always known for her honesty and sincerity, she became an expert in deception when it came to hiding her bout with anorexia nervosa.

It was later revealed that Richard was simultaneously battling his own demons -- an addiction to Quaaludes -- and entered a six-week chemical dependency program in January 1979. Just two weeks in, Karen revealed plans to record a solo album, something she'd longed to do for years.

With Phil Ramone at the helm, Karen set forth on a creative mission of experimentation and soul-searching. She realized this break from the duo and family was the perfect opportunity to explore and to push the envelope musically. It was time to establish herself as an independent 29-year-old woman. Friends called the project her "emancipation proclamation."

Champagne toasts and congratulatory cheers flowed freely during the solo album playbacks in New York, but on the West Coast, brother and label execs sat stone-faced as Karen shared the recordings. She was deeply discouraged after hearing that Richard felt the album was "shit" and eventually folded under pressure, agreeing to shelve the entire project. She retreated to Los Angeles and went to work with Richard on a new Carpenters television special.

In 1980, Karen rebounded in a whirlwind relationship with smarmy real estate developer Tom Burris. The two wed in a posh ceremony at the Beverly Hills Hotel on August 30, just four months after their first date. The disastrous marriage was short-lived, serving only to exacerbate the bride's mental illness and physical descent. By the time the couple split in November 1981, Karen's weight had plummeted to below 90 pounds.

Eventually owning the anorexia, Karen set off on a recovery mission, relocating to New York City in January 1982. She arrived at the office of self-styled eating disorder expert Steven Levenkron weighing just 78 pounds and nursing a deadly cocktail of diuretics, laxatives, and even thyroid pills to speed metabolism. It was later revealed that she also abused ipecac to induce vomiting. Karen's condition only worsened and she was eventually admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital in September for hyperalimentation (intravenous feeding). Gaining a quick 30 pounds and a dose of momentum, she proclaimed she was fully cured and checked herself out of the hospital, returning to Downey in time for Thanksgiving. Within three months she was dead.

On the eve of her death, Karen phoned Phil Ramone and the two spoke of the infamous solo album. Ramone encouraged her to look upon their work together as a positive milestone in her career, regardless of the way it was received by others. "You will make many more records with your brother," he told her, "but don't lose the landmark just because it's not out in the marketplace."

"Can I use the f word?" she asked.

"Yeah," he said.

"Well, I think we made a fucking great album!"

Following Karen's death in 1983, fans were relentless in pushing for the solo album's release. Posthumous vindication finally came in 1996 when Karen Carpenter -- the album -- finally hit record store shelves. Outtakes from the sessions surfaced on the Internet a few years later and provide an intriguing glimpse into a daring and exciting departure for this sheltered, tortured soul.

See rare photos of Karen on the following pages. Little Girl Blue is now available in paperback.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes