From the legendary gay falsetto known for Bronski Beat, the Communards, and his pioneering solo work comes Homage, a disco album that keeps his political beat alive.

March 09 2015 9:00 AM EST

deliciousdiane

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

From the legendary gay falsetto known for Bronski Beat, the Communards, and his pioneering solo work comes Homage, a disco album that keeps his political beat alive.

In my rural Idaho hometown in the 1980s, my friend Jeff and I lived for MTV. Most of us kids did, in fact. Jeff, my best friend was a swimmer, a New Wave music lover, and a preppy fag -- or at least that's what some of the kids at school called him. They said it to his face, as in "Hey, Preppy Fag, what's up?" When an older kid beat the hell out of him our sophomore year, I remember the kid just yelled "fag." I was a closeted bisexual at the time. So in 1984 when a video for the song "Smalltown Boy" by the Euro synth-pop band Bronski Beat premiered, it was like the story of our lives on screen.

Widely considered the first real gay video on MTV, it featured singer Jimmy Somerville -- who gave both Bronski Beat and later the Communards their signature falsetto sounds -- who flirts with a swimmer in the high school locker room and is later attacked by homophobes and disdained by his father. Over a chorus of "run away, run away" we see Somerville on a train, leaving that little town for a bigger, queerer life in the city. Two years later, we followed Somerville's lead and left Idaho.

That song, though, became a huge gay anthem, and a global success: hitting the top 10 on the music charts in the U.K., the Netherlands, France, Canada, Australia, Belgium, and Switzerland. In the United States, it was number 1 on the dance charts. It's been covered dozens of times since then, by Dido, metal bands (Paradise Lost, Delain, Deadline), orchestras (Ireland's RTE Concert Orchestra), and even the French New Wave (Indochine).

"I've just been listening on Soundcloud to a version by a band called Heavy Ball," says Somerville, on the heels of his new album release. "Oh my gosh, it's the best cover version of 'Smalltown Boy' I've ever heard. It's boy's guitar band, but the man's voice is just -- he nails it; it's like it's a different version, but it's really great."

Now, 30 years after the release of "Smalltown Boy," Somerville has entered a new, nearly euphoric chapter in his career, with a new album, Homage, that is as unabashedly political as his early work but also brilliantly written and a wonderful celebration of the music that inspired him. With Homage, Somerville returns not to pure New Wave or even pop but to the sounds of disco. That diverse genre was a consistent thread in Somerville's personal and musical life. Some of the biggest selling tracks amongst Somerville's colorful career are his unique takes on some of the anthems that defined the disco era. Covers of classics such as "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)," "Never Can Say Goodbye," and "I Feel Love," with Somerville's unique, instantly identifiable voice made the singer one of the defining voices of the '80s and '90s. The Communards' "Don't Leave Me This Way" and the Thelma Houston version (itself a remake of a Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes original) became a sort of hymn or psalm during the early AIDS epidemic. If you were there, you heard it numerous times a week, in bars, homes, hospitals, and even at graveside.

(RELATED: A Career Overview for Pop Icon Jimmy Somerville)

With Homage (which is produced by his longtime producer John Winfield), Somerville isn't remaking disco classics as his own; he's creating original disco anthems, a hefty fete in this post-disco, post-grunge, Taylor Swift meets Kanye West musical world.

The first release from the album, "Travesty," written by Somerville, has all the exuberant jangle of classic disco but the lyrics offer up a different story, with a refrain that it's "time to wake up, it's a welfare war ... life must mean more than this, find a better way." Any concerns I had about Somerville losing his edge were gone within minutes of that first track on the album.

"It's really interesting because that lyric ... I think as we grow older, we're sometimes uncomfortable about being political or activists," says Somerville. "Actually, more than any other time I think in my political history this is like a welfare war. We are in a time where everything is being changed in respect to welfare and it's not just about what money the government pays out to people who are vulnerable; it's just about the welfare that we have for each other. I think we're in the age of consumption and self, and self obsession that it's just like hyperbole. It's unbelievable. I find it completely like, 'whoa!' So I suddenly thought, actually it's a welfare war because we're heading for sticky times, I think."

Culturally, Somerville says we're disconnected, and he tried to get that out in his song. "We don't know how to communicate, or how to even look after each other -- that's what worries me," he says. "There is going to be this new generation of kids coming up who really won't understand what it is to look out for each other."

Still, he has a sense of humor about it. When I mention how disconcerting it is that generally the younger generation must look after us in the older generation, so that disconnection could be an issue, Somerville smiles. "Definitely. That's why I've been saving up so that I can have a little stash that's put away so that I can basically entice younger men to look after me because there's a financial gain."

More on the next page >

Disco, which "always played a part in my life ... ever since I was a kid," is Somerville's saving grace even now. "I defy anybody who hears 'Boogie Wonderland' not to, somewhere within their body, be twirling," he says. "I just feel, me personally, I'm in this period of kind of uncertainty, where every day when I go out on my bicycle, my eyes are everywhere just thinking, 'Oh, my God, people are crazy, people are crazy.' So I just thought, this is good antidote. And it's so strange, because I didn't understand, really, what disco is until I made this album -- and the organic, feel-good factor and the love that goes into it."

Still he says, disco is political. He points to Shirley and Company, who sang "Shame, Shame, Shame." "The cover of that album is basically her dancing with Richard Nixon, you know?"

Some of the songs on Homage have "actually have been around for a while," he says, "and then when we put them to disco arrangements, I suddenly realized, 'Oh, my God, they were basically these closet disco songs, really.'"

The kind of gay political commentary from his early pioneering music is there too. "Yeah, because I'm a gay man, so everything I do and I say is about kind of who I am, where I am, and what is happening, and what the political climate is and what the social climate is."

On the new album, he says, there's a track about "how I feel about myself, and where I am, and never really fitting in even with my musical community, with gay life and stuff -- I've always been slightly outsider-ish."

Another song, "Freak," the chorus sings, "I need a freak of a man to call my own, I need a freak of a man to be mine." Somerville says, "it's about finding somebody who is not going to be scared to be who they are and to be true and to say what they think and feel."

Is he still looking for that? "I kind of decided that that is where it's all going wrong, so, it will find me. I've realized that it'll find me, so I'm just kind of biding my time. And if it doesn't, if it somehow misses the bus, then that's OK."

It was unabashed queer protest music at a time when we only had each other, and half of us were dying and half of us were caretaking. The time period hit Somerville hard. He was at the peak of his commercial success with the Communards when he began to unravel. "I went to a really dark place with it, because I couldn't process in my head why everyone was dying -- and why I wasn't. Why wasn't I positive? Why wasn't I getting infected? This is the stuff that would run through my head, so I had this kind of survivor's guilt. It was a strange, perverted sort of almost pity, like, 'Why is it not happening to me? Why is it happening to all my people, my friends, all the people I've had relationships with, and yet not me?' So I really did go into a dark place."

He says it took a long time to come out of the spiral, and it coincided with fleeting fame. "When you're incredibly famous, and having all of that, and then that starts to wane and suddenly you're left without that ... it's been proven to have effects. It has the same power, and the same high as like the effects of cocaine in what it does to your head." Somerville laughs, but he's serious too.

"Because I didn't know how to deal with that, I had to find my own ways to deal with that," he says. "It really affected my confidence and what I wanted to do, and what I was doing. I did come out of that, but I had to hit a rock bottom, to actually understand, I can't go any lower than this."

His rock bottom? "Co-dependency and dependency. I've always had some issues with alcohol, and that allowed me to then just go into a much darker place, and then it took me to darker places, and I kind of lost control of that. But I managed to get myself out of that, and it's been the best thing that's ever happened to me. It has allowed me to re-engage with reality, and a much more healthy perception of reality. It's also helped me onto a new level of creativity which I never ever had before."

That Somerville's more creative now at 53 is a testament to the endurance of this uniquely queer performer. Not only a singer, Somerville appeared in the 1992 cult film Orlando and in Isaac Julien's 1989 gay classic Looking for Langston. Even while falling apart, Somerville kept creating, kept pushing envelopes.

While other Euro-synth or New Wave bands flirted with homoerotic imagery in their videos (most of them, actually) or euphemisms that LGBT people could interpret as gay, Somerville has always been out, and his music, too, has been out from the beginning. With Bronski Beat (band mates Steve Bronski and Larry Steinbachek were also gay), Somerville sang to other men, not to women, something unheard of in mainstream music in the '80s. It's barely heard of now. "For me as a gay man that's always been important," he says of the pronoun usage in his songs, "since the very, very early days, since the first album, The Age of Consent. You know, we did 'Need-a-Man Blues.'"

That 30 years later, few gay male musicians are following his lead is disheartening. How many singers can you name that sing gender-specific, same-sex lyrics?

"Even the [gay musicians] who are out now, there is still that fear that they're going to alienate," Somerville admits. "You know what, I would rather be honest and alienate rather than just lie and assimilate."

Somerville said he's long understood that to be true. "Someone told me something really early on, and that's when I realized I'm doing the right thing," he says. "It was a man, and I was somewhere, and he was very honest with me and he says, 'I don't like what you do, I don't like what you stand for, but I can do nothing but admire your honesty and respect your honesty.' And I realized this is what it is about. This man is respecting me, doesn't like what I am, but he respects that I have balls and the guts to be who I was and not to lie and not to pretend."

He says sometimes performers still "underestimate" what people's reactions will be because so many look beyond labels these days. He says, though, if you're the type of person who likes listening to the whole "Jamaican dance hall stuff about shooting and killing gays ... you might actually want to ask yourself why you find that kind of stuff OK. [Being gay is] just being who you are as a person and choosing who you love and all that kind of stuff. It's just strange that that can provoke such negative and fierce reaction from someone to the point where they actually believe you have no right to exist. That never fails to baffle me. It really doesn't. I still can never get my head around that, and it kind of makes me sad, but I accept that it seems to be part of the human condition."

He's less in the limelight now, so he doesn't get that kind of hatred on a regular basis, the way he could decades ago. "There will always be people who will disapprove, and people who will go out of their way to make life difficult and even to be quite extreme in their reactions, so I'm always aware of that."

He's still proud that he was out from the get-go. He won't speak harshly, but he doesn't quite understand other gay performers, like Lance Bass of 'N Sync, who come out only after becoming famous. "It's just such a shame that, it's, I guess, a bit of a choice for a lot of people -- it was about career first and sexuality second. It's a personal choice, but I personally just think it's sad that you have to make that choice about being so closeted to the point where it actually then turns it into something shameful and secretive, and you're embarassed, and ashamed to be who you are. And not being honest, you know? Like you just kind of somehow have something to hide."

He says we should be leaving that behind in 2015. "But it still is out there, and, I'd imagine, we'll never know at any given time how many people are actually living secret lives. That's the sad part. We will never ever know, really, how many people are living secret lives. It's a fear of rejection, it's a fear of the unknown, it's fear of ridicule, it's fear of discrimination, and it's a fear of losing things as well, because, again, reactions can be so extreme sometimes depending on where you are and what your environment is."

The crooner turned activist never had much of a choice. A handsome man with a falsetto and pure lust for other men, Somerville wasn't likely to fly under any radar, even in the 1980s. For him this was all one package, the personal and professional. "What I was doing, it was about passion, it was about an awareness of discrimination, an awareness of my own identity, and I was so, so adamant I would never suppress that or hide that any amount of success," he admits. "I knew there would be a price to pay for that. I knew that we would never break America, I knew that we would never have any success in that way because, as soon as they did start to find out in America, about who Bronski Beat was ... the radio stopped playing stuff, and it was never going to transfer onto a wider audience. But that wasn't why I was doing that in a wider sense."

He says he became a part of a pop band to make pop records, to be successful, but, "I wasn't prepared to compromise my own personal integrity, or to actually compromise my identity for that success, so, it was sort of doomed in some respect because the record company would want you to become very successful, but that's not going to happen if you have this big, huge elephant in the room."

And Bronski Beat was super gay. The album, Age of Consent, had a pink triangle on the cover (a nod to what the Nazi's branded homosexuals with) and inside on the cassette liner notes (which every kid read back then, hoping the lyrics were printed) were age of consent laws around the world and a gay hotline number. It was a bold, almost revolutionary statement in the eyes of young queers like myself.

"Yeah, what we understood was, we, not even just my voice was a platform, we could use the medium of the artwork, the medium of the album being in a record store, someone could read that, so it'd almost be like someone lifting up a little information leaflet. 'Oh, there's a number here I can call, a gay help line.' We were kinda realizing, actually, we could take information to a bigger audience, and not necessarily just a gay audience, a wider audience as well. We definitely started that kind of debate because we were everywhere, we were kind of in-your-face, really."

More on the next page >

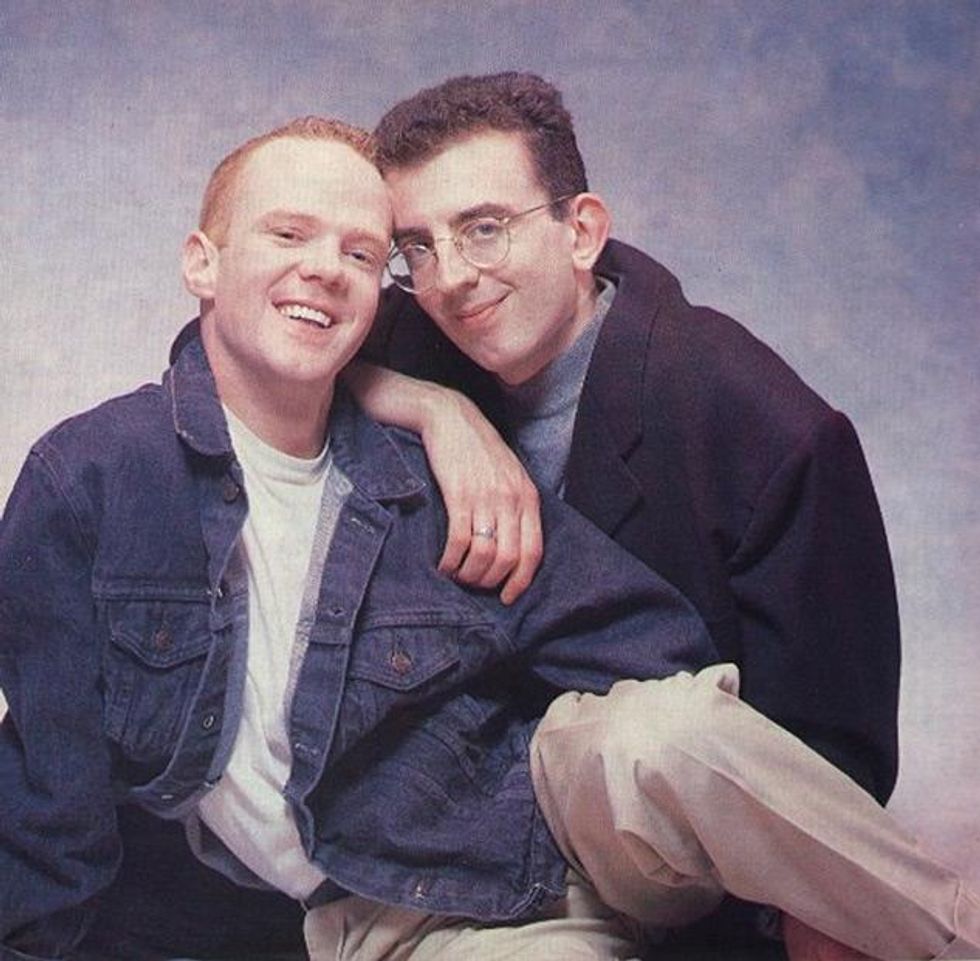

Then came the Communards, and Somerville and his band mate Richard Coles (who later became a journalist and a priest) became huge hits. "That, again, that was pretty incredible. In some respects, it was double-edged. Richard and I were involved in a very political time, and then also it was around the whole AIDS scare and all the discrimination and the shock tactics of the media -- and we found ourselves suddenly in the middle of that, doing interviews for like, teenage pop magazines. We were actually trying to give out this information to counteract the disinformation that was being out there in the media, so we were constantly trying to be one step ahead, or actually correct what had been put out there about AIDS, about gay men, all that kind of stuff. It was scary times, because some of the stuff that we'd get thrown at us, like 'AIDS carriers'...but at the same time, it was very powerful for us, because we became incredibly successful, at that point, we probably were, then within Europe, one of the biggest pop bands in Europe. Our visibility was really up there."

That they were gay wasn't the only revolution though. Their live band was all women musicians and on stage and in interviews the band would infuse politics into their musicial celebrations, educating people without them even realizing it.

"And personally, we were dealing with some really heavy stuff, especially myself. I was dealing with a lot of loss, a lot of kind of, fear myself around the AIDS crisis, about people disappearing ... and all of this stuff was on top of the fame. It was like a real storm just brewing and brewing." He and Coles were proud of their politics, their gay visibility, "so we didn't want suddenly the focus to be on how we were falling apart, so we realized it was best if we stopped before that became so publicly visible."

So the Communards broke up in 1988. "Now that I look back on that, I think, actually, that was a really good thing to do, and it was a brave thing to do, because we were heading toward another album, we could've just milked it, we could've just run with that success, but we were kind of realistic as well. We kind of realized that we were both personally having some real serious issues, so we decided to call it a day."

After having survived the early AIDS epidemic, after losing so many friends and lovers and exes to the disease, Somerville says he's often disturbed that HIV isn't more of a concern among young gay men, even in the U.K. "And it's really strange," he admits. "I had the most bizarre experience talking with a much younger man, and he has a bigger fear of gonnorhea than he does of HIV because he's now very aware of these new strains of STIs, which are now resisting antibiotics, and there are no other drugs to try to combat that. So this is what he's scared of. There is a generation that now understands that if you're HIV positive, you get the meds, and then eventually you become undetectable, and then life is OK. It's that kind of scenario, it's very difficult to get the head round, really."

He comes from an older generation, he admits, who "saw the very beginnings of the whole AIDS epidemic and the whole HIV crisis and everything that was involved with that, from how the media were to reaction to medication to how it affected people. That's such a kind of massive part of our shared history, but for some, our younger generation, they can't relate to that, they don't understand that. And there's less talk about it. You don't see much around about it, although here ... when you go to those websites and social media hookup places, you get lots of stuff popping up where you can go for free HIV and STI tests at various bars and clubs, because we have a huge, massive problem in the U.K., especially in London, of drugs and sex, and this whole slamming phenomenon, which is, uh, there's a younger generation who are out here getting infected with HIV because of the drugs and the needle sharing and the sex parties."

Slamming? "I don't want to get it wrong," Somerville says when I ask him to explain it to me. "But slamming is kind of where it revolves around crystal meth and it's like sex parties, and it's injecting and shooting the drug. It's called slamming parties, and it's a big problem."

After the sex and drugs and HIV talk, I have three minutes left to bring it back to Somerville's amazing new album, or rather, his long legacy of musical success and gay pioneering. When Somerville covered Sylvester's "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)" in the 1980s it introduced a younger generation to the legendary gay disco diva. So how does this musical mastermind want to be remembered in 20 or 30 or 50 years by the next generation?

"I would just like them to listen to the songs and, I would just like, I would like to hope that rather than not thinking about who I am or what I was, or who I was, but just to listen, and hopefully have a tingle, and to get that tingle, and to get that emotional connection, and that's really all I want. And I think 'Smalltown Boy' has done that over the decades. It just hooks into the heart, and that's why I would like to be remembered, the fact that I was able to have songs that could sink into your heart. Actually, have you ever heard Sylvester's live version of 'Mighty Real' that was recorded in San Francisco? If I listen to that, I never fail to get goose bumps all over. I go crazy. That song just makes me so emotional."

Of course, that's how I feel listenting to Somerville's songs, from "Smalltown Boy" to "Read My Lips" to Homage's "Strong Enough." Goose bumps indeed.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes