There’s a scene in Patricia Rozema’s 2018 film Mouthpiece where the main character, Cassandra, is flooded with a memory of her mother, who’s just died. The camera pans the room, lingering on Cassandra’s mother’s books and music. In the frame there appear works by Joni Mitchell, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, and the groundbreaking lesbian author, actor, and activist Ann-Marie McDonald, who appeared in Rozema’s first feature, 1987's I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing. Through Cassandra’s memories of her mother, Rozema pays tribute to Canada’s great women storytellers, and considering the filmmaker’s body of work, her name belongs among them.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

With a recent retrospective of Rozema’s films in New York City and an upcoming look at her career set to run in Los Angeles, the director behind innovative lesbian-themed films including I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing and 1995’s When Night Is Falling, is also revisiting her work. The retrospective that runs at the UCLA Film and Television Archive April 26-30 and at Laemmle theaters in Los Angeles May 7-8 and 13-14 includes 4K restorations of I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, White Room (1990), When Night Is Falling, and Mouthpiece.

Throughout her canon and evident in the restored films is Rozema’s singular poetic film language that includes queer identity, interior monologues, and a duality in her characters or what she refers to as “twoness.” Unburdened by the machine of Hollywood and working from artists’ grants from Canada, Rozema cemented herself as a true auteur out of the gate with I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, a self-reflexive and heartfelt comedy about a quirky secretary to a lesbian art gallery owner. The film investigates the nature of art itself, something that Rozema would continue to examine throughout her career.

“[Living] in a country that understood that if we were going to have any culture at all, [and] living next door to, you know, the giant that is the U.S., we’re going to have to subsidize the artistic voices, I was one of those subsidized ones,” Rozema tells The Advocate. “So I wasn’t thinking market.”

“I was just thinking, Oh, Margaret Atwood comes from here. Oh, Alice Munro comes from here. Oh, women can be storytellers,” she adds. “I think being such an outsider in my early formation gave me the courage, I guess, to just continue in my outsiderness in filmmaking.”

Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava as Cassandra in MouthpieceKino Lorber

Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava as Cassandra in MouthpieceKino Lorber

While Rozema revisited the critically praised I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing during its rerelease in 2022, it’s been some time since she took another look at White Room. That film marries genres including the fairy tale and crime thriller when her male protagonist witnesses his favorite pop star’s murder from the bushes below her window. Rozema’s themes of “twoness” and a subjective inner monologue are still prevalent, even if the movie did not fare well critically in 1990, due in part to an unfinished version that screened at Cannes that year. With the retrospective, it has been overwhelmingly positively reevaluated by film lovers new to Rozema’s oeuvre.

“I don't go back [to my films] very often, because I am afraid of developing a shtick or just becoming too aware of my own propensities artistically,” Rozema says. "It’s all about staying alive and awake. … Because of the restorations, I’ve been going back over them. And you know, at [the Toronto International Film Festival] it was very exciting actually seeing a couple of films with people who had seen none of my work. And, shockingly, the young ones are often really drawn to a film that was an abject failure in its time, called White Room.”

“That's been moving to have younger sort of cinephiles gravitating towards that one, because I felt really terrible about that movie for a long time. I felt like I made a huge misstep,” Rozema adds of seeing her work in a new light. “I almost felt like I don't know if I'm strong enough for this business.”

Maurice Godin as Norm and Kate Nelligan as Jane in White Room Kino Lorber

Maurice Godin as Norm and Kate Nelligan as Jane in White Room Kino Lorber

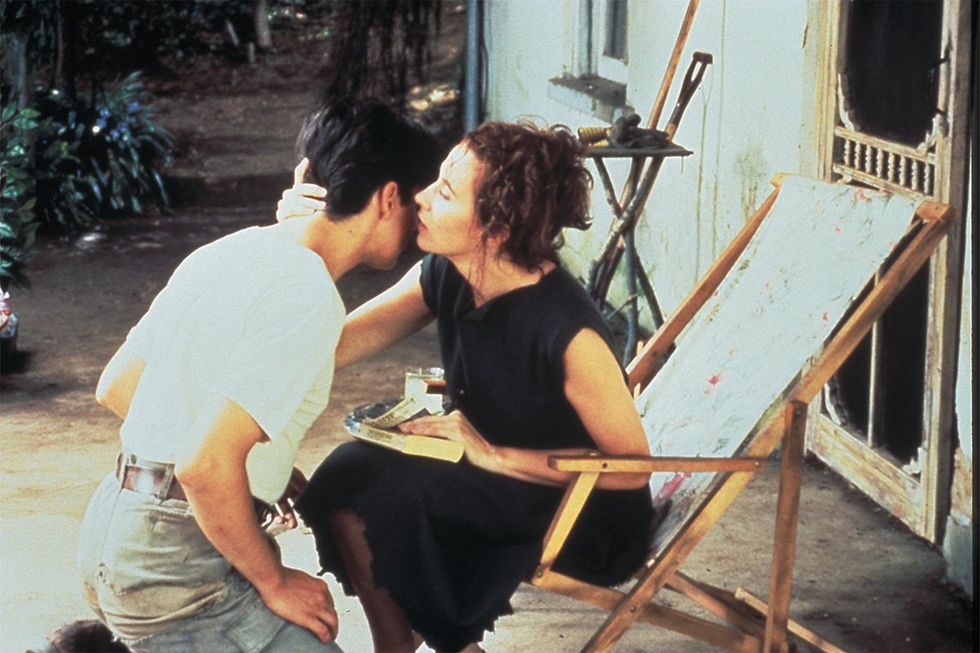

Thankfully, Rozema kept working. To move through what she viewed as White Room’s failure at the time, she began working on her now lesbian classic, When Night Is Falling.

“I thought, Oh ,gosh, you know, one’s admission into this profession is not a guarantee. There’s no tenure here. I better make the one that I started out wanting to make,” Rozema adds. “I didn't want to do it first, because I wanted to have a little bit of control over my craft before I attempted it.”

In that film, transformation, mythology, and religion converge when Camille (Pascale Bussières), a young professor at a religious college, falls for Petra (Rachael Crawford), a free-spirited traveling circus performer. Though Rozema, who was raised as a Calvinist, had been out in her personal life for some time, she was aware her lesbian identity could become the primary descriptor of her work at a time when there were few films about lesbians with happy endings. Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts (1985) and Rose Troche’s Go Fish (1994) were outliers.

“I didn’t want to be limited from telling heterosexual stories or any kind of stories, because I just didn’t know where I was going and what I was doing. And I didn’t only want to tell one kind of story,” Rozema says. “So I was worried about some creep in Cincinnati saying, ‘Tell me about your first sexual experience.’ I was terrified of having to dodge those questions whenever I was in public or wherever.”

“But I think I was protecting my ability to make movies, because I was ambitious too. Not for fame or for money but for being able to make movies, which is the best job in the whole fucking world in my mind,” she adds. “I was terrified that I would be shut down. So I was careful, maybe too careful sometimes, so that I think some people wished was different sooner.”

Despite Rozema’s thoughts of being “too careful” at some points, as a progenitor of the Toronto New Wave with the likes of Atom Egoyan and Jeremy Podeswa, her contributions to cinema include making elevated films about queer women with happy or hopeful endings that expanded the notion of fixed sexuality.

“I also spoke quite early about fluidity, a gender continuum, and a sort of orientation continuum,” Rozema says. “At the time, it was very binary: You’re gay or you’re straight. Period. I felt like there's got to be more colors in this human palette.”

More than 35 years after her first feature was released, Rozema continues to impact storytelling, especially about women and queer people, including with her adaptation of Mansfield Park (1999), her kids’ movie Kit Kittredge: An American Girl (2008), and her dystopian Into the Forest (2015), which starred queer icons Elliot Page and Evan Rachel Wood. She’s also made a foray into television, directing episodes of In Treatment, Mozart in the Jungle, and Anne With an E. Through it all, she’s expanded cinema through her subjects and style.

“I feel like women are actually just discovering themselves and the whole queer population is just discovering themselves. Because we’ve only ever had, or mostly had, 90 percent straight white men defining ourselves to ourselves. Women have been learning about being women by watching what men wanted them to be,” Rozema says.

Thankfully, Rozema shows no signs of slowing even as her career retrospective reminds older audiences of her artistry and introduces new viewers to her.

Screen Rozema’s films in Los Angeles at the UCLA Film and Television Archive April 26-30 and at Laemmle Theaters May 7-8 and 13-14.

Rachael Crawford as Petra and Pascale Bussières as Camille in When Night is Falling Kino Lorber

Rachael Crawford as Petra and Pascale Bussières as Camille in When Night is Falling Kino Lorber

Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava as Cassandra in MouthpieceKino Lorber

Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava as Cassandra in MouthpieceKino Lorber  Maurice Godin as Norm and Kate Nelligan as Jane in White Room Kino Lorber

Maurice Godin as Norm and Kate Nelligan as Jane in White Room Kino Lorber  Rachael Crawford as Petra and Pascale Bussières as Camille in When Night is Falling Kino Lorber

Rachael Crawford as Petra and Pascale Bussières as Camille in When Night is Falling Kino Lorber

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes