The ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives helps celebrate Pride month by remembering our past. Here's a guided tour through our history courtesy of ONE.

June 12 2013 6:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

At ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, LGBT Pride Month holds a special place in our hearts as time to commemorate LGBT people collectively declaring, "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!" Let's walk down gay history lane and explore the origins of Pride by taking a closer look at those electrifying evenings in June when LGBT people decided to stop hiding and start fighting.

The Good Fight Had Already Begun

In reality, early homophile organizations had been organizing for years prior to Stonewall.

Groups like the Mattachine Society, Daughters of Bilitis, and ONE Inc. were operating in a handful of cities raising awareness about employment discrimination, homophobic laws, police brutality, and other problems the LGBT community faced at that time.

During the 1960s, activists were picketing in various locations with moderate success, including the "Annual Reminders" every July 4 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, in front of the White House, and demonstrations like the one at the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles to protest a police raid of the bar a few days before.

It has been said that during the turbulent '60s, gay bars were to gay people as churches were to African-Americans in the South. They were temporary refuges, sanctuaries where one could find a brief respite from the stifling homophobic heat of the outside world.

For the most part, pre-Stonewall activism tended to be fairly regional and was made up of several independent fledgling cells of a not-yet-born national gay civil rights movement, a movement that still lacked a collective power large enough to draw its foot solders out of hiding and onto the streets.

Then came Stonewall.

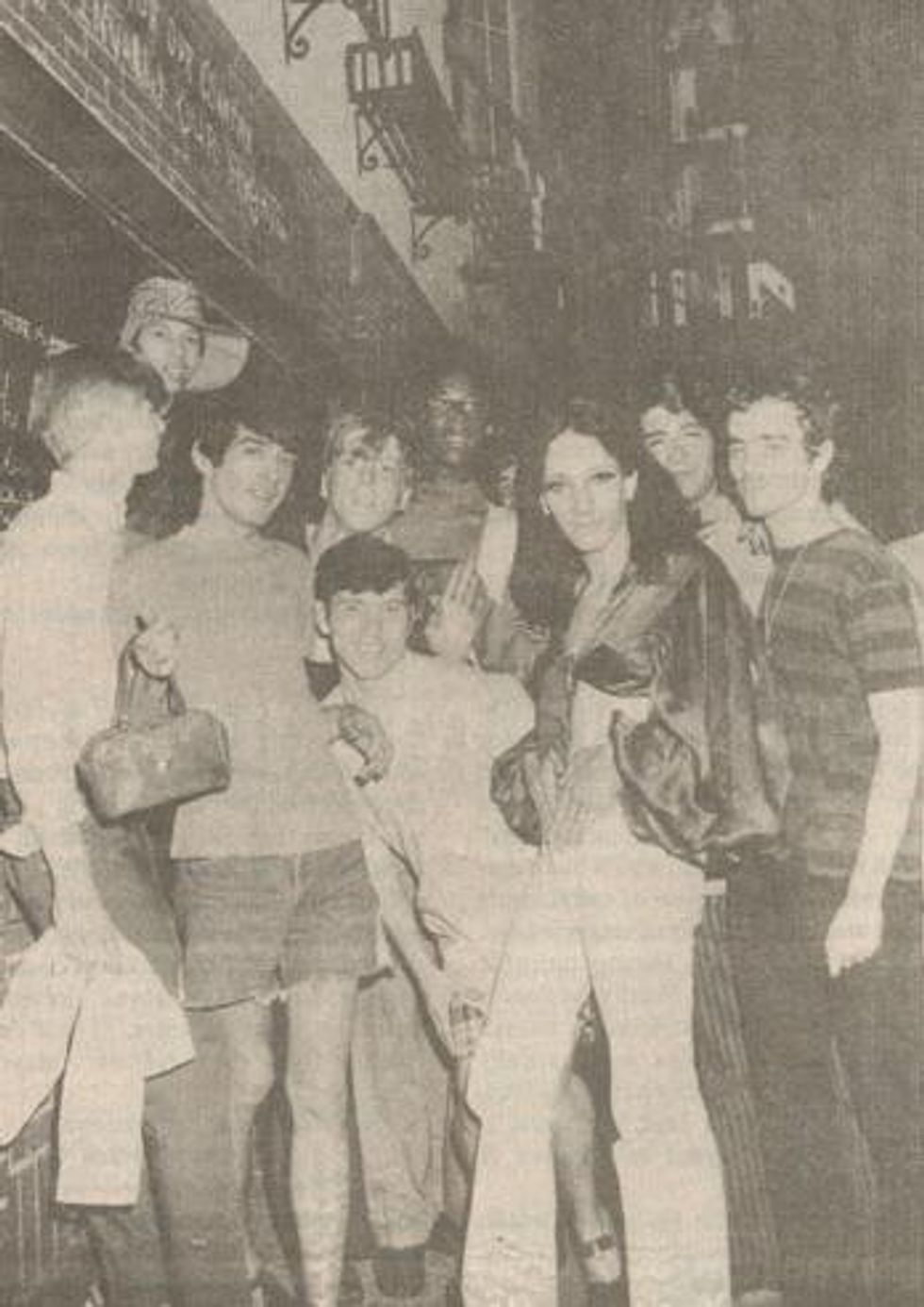

Above Right: Patrons of the Stonewall Inn. Above: Dottie Frank (center) with others at Acme Bar, circa 1961

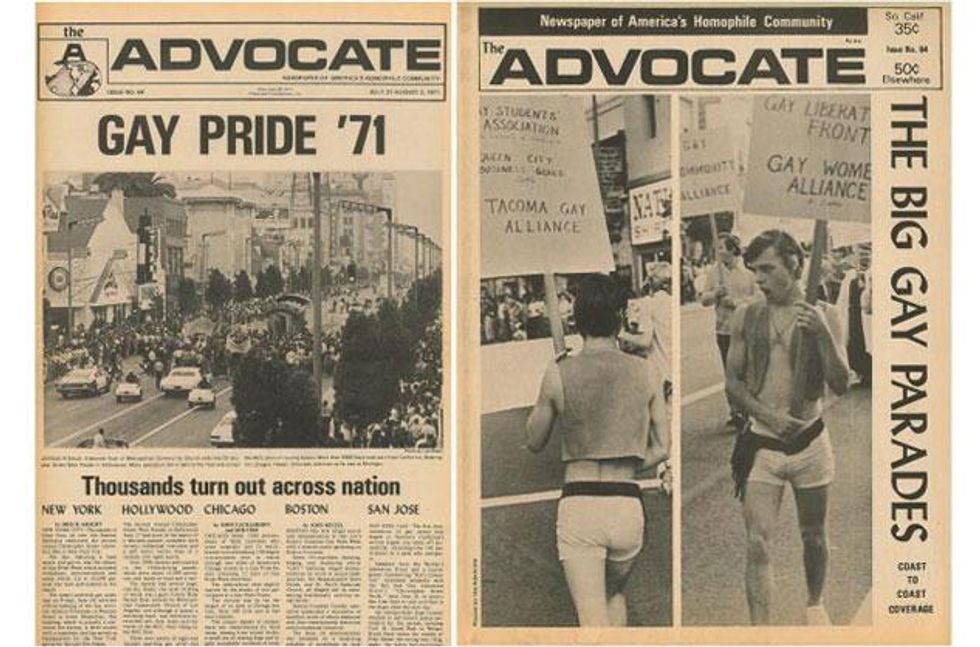

Above: Clippings from The Advocate covering the parade.

Pride Is Born

Everyday life for a gay person in the '50s and '60s included the very real threat of being strangled, shot, jailed, blackmailed, evicted, fired, excommunicated, forced to undergo electroshock therapy on your genitalia, or, if you were one of the unlucky ones, going in for an analysis of your "sexual perversion" and coming out with a full frontal lobotomy.

So that night when the police raided the Stonewall Inn, they got a lot more than they bargained for.

"We were tired of being targets of manipulation and exploitation; tired of being maggot excuses for raids upon our assembly, tired of being someone else's scapegoat for some other reason. Tired of being threatened and harassed and entrapped and told what we were, what to do, and how to do it, when to do it, how to feel, what to say, how to be, what to be..ya can't be it outside, nor can you inside! We rioted because rich, or poor, young or old, we dared to be ourselves. We wanted to be ourselves, to be, to laugh and play in joy! We rioted to be gay." -- Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee member, 1974

A groundswell of deep systemic anger, defiance from a community on the edge of revolution, and the fervent freedom that comes with having nothing to lose came together to form the perfect storm that night. The fire had suddenly and spontaneously been lit and a new national gay civil rights movement had been given a pulse.

The Stonewall riots changed the direction of the gay movement, taking it from several independently run nascent organizations sprinkled throughout the country to becoming a full-fledged national social equality movement that people could identify with and organize around. Not wanting to lose the momentum gained from Stonewall, the newly empowered LGBT rights leaders in several different cities began mobilizing, trying to answer the question "Now what?"

On November 2, 1969, at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations in Philadelphia, the first pride march was proposed by way of a resolution. The Christopher Street Liberation Day march was then held in New York City on June 28, 1970, marking the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots with an assembly on Christopher Street and a march covering the 51 blocks to Central Park.

On that same weekend in 1970, three other U.S. cities, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco, also held what would be the first Pride events ever in U.S. history. Los Angeles is credited as having the first official city-sanctioned Pride parade (as opposed to a march), as it was the only event that had a permit for street closures and an actual parade route. In 1974, Los Angeles added the first festival component, which is now a major part of Pride celebrations nationwide.

In 1970, walking in broad daylight with a sign saying you were a homosexual was not only terrifying but could prove deadly. Many of the marchers in those first Pride events were genuinely scared they might not make it to the end of the route. They had no idea where they were going to finish or if anyone would show up to march with them or if they would even make it halfway down the street without being mobbed by an angry, violent crowd.

As the march began that first year in New York City, 10 people became 100, and then 100 people became 1,000, and by the time the march ended, there were thousands marching in solidarity for a world where loving someone of the same sex could be as American as apple pie.

Above: Christopher Street Liberation Day flier -- Christopher Street Liberation Committee Collection, property of ONE National Gay amd Lesbian Archives

The first Christopher Street West pride parade in Los Angeles, 1970

The crowd holds hands at the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade, 1971.

Men hold a "Black Gays Unite" banner at the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade, 1975.

Lesbian couple at the festival following the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade, 1975

Police officers holding hands at the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade, 1972

Dykes on Bikes leads the procession at the Los Angeles Christopher Street West pride parade, 1978

LGBT protesters picket the ABC offices concerning the broadcast of the Marcus Welby, M.D., episode "The Outrage." The demonstration was one of many over the misrepresentation of LGBT people by the media.

Gaby front cover and inside pages: Behavior modification product manual advertising electroshock therapy devices used to treat homosexuals in the 1950s, property of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

One of the "Fagots [sic] Stay Out" signs that instigated the Gay Liberation Front protests against Barney's Beanery. 1969.

Gay Liberation Front protest on the streets regarding the first gay pride parade permits, June 1970

"Let Every Pansy Bloom" banner at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day pride parade, June 25, 1978

Gene Kittridge, owner of Gene's TV and longtime gay philanthropist, contributes money to Jim Kepner (second from right) of the National Gay Archives. Standing far right is Gary Hundertmark, past archives board president, 1980.

Above left: Jim Kepner (left) and W. Dorr Legg standing outside the ONE Inc. offices on Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles; undated. Above right: W. Dorr Legg stands before ONE Inc. staff and author Harry Otis (far right), circa 1957-1958.

Core ONE Inc. staff (from left ) Don Slater, W. Dorr Legg, and Jim Kepner, circa 1957-1958

Here at ONE Archives, we think one of the best ways to celebrate LGBT National Pride Month is by taking Pride in your past. This June, when you attend your own Pride celebrations across the country, take a moment to remember those early LGBT activists who bravely paved the way for us before and after Stonewall. They were willing to risk everything to defend our right to simply exist.

We stand on their shoulders today as we work toward marriage equality, national federal employment protections, and putting an end to antigay violence, among many other rights and protections we are still seeking. Their legacy has now become our legacy ... let's take really good care of it and make them proud.

"Freedom is never given -- it must be taken" -- Gay Liberation Front Newsletter, 1970