Executives were terrified to make the film. In spite of fears and interference, a memorable film was made with a talented cast.

November 10 2010 10:30 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Executives were terrified to make the film. In spite of fears and interference, a memorable film was made with a talented cast.

In 1985 the AIDS epidemic had claimed more than 5,000 lives. A Gallup poll in June of that year established that 95% of Americans had heard of acquired immune deficiency syndrome, but most presumed that it solely affected gay men. In October actor Rock Hudson succumbed to AIDS complications, raising awareness and fears. Mainstream American media warned that the virus had entered "the general population," suggesting that the hemophiliacs, people of color, sex workers, and homosexuals already infected fell outside that classification.

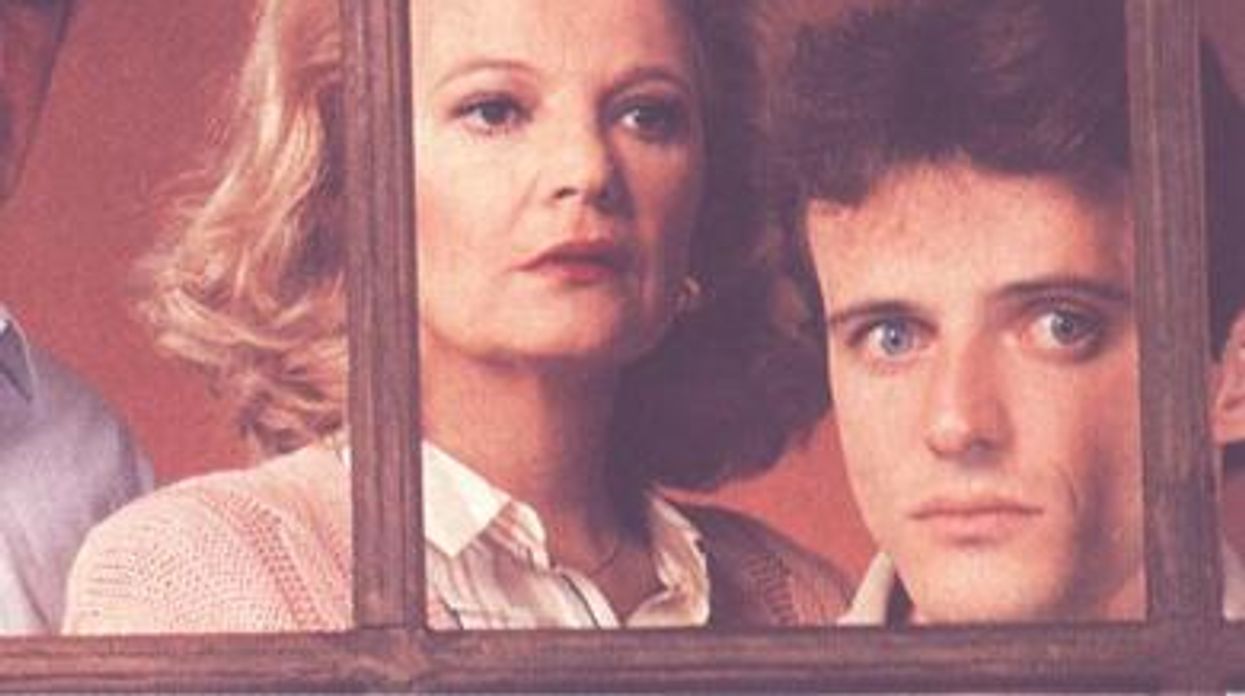

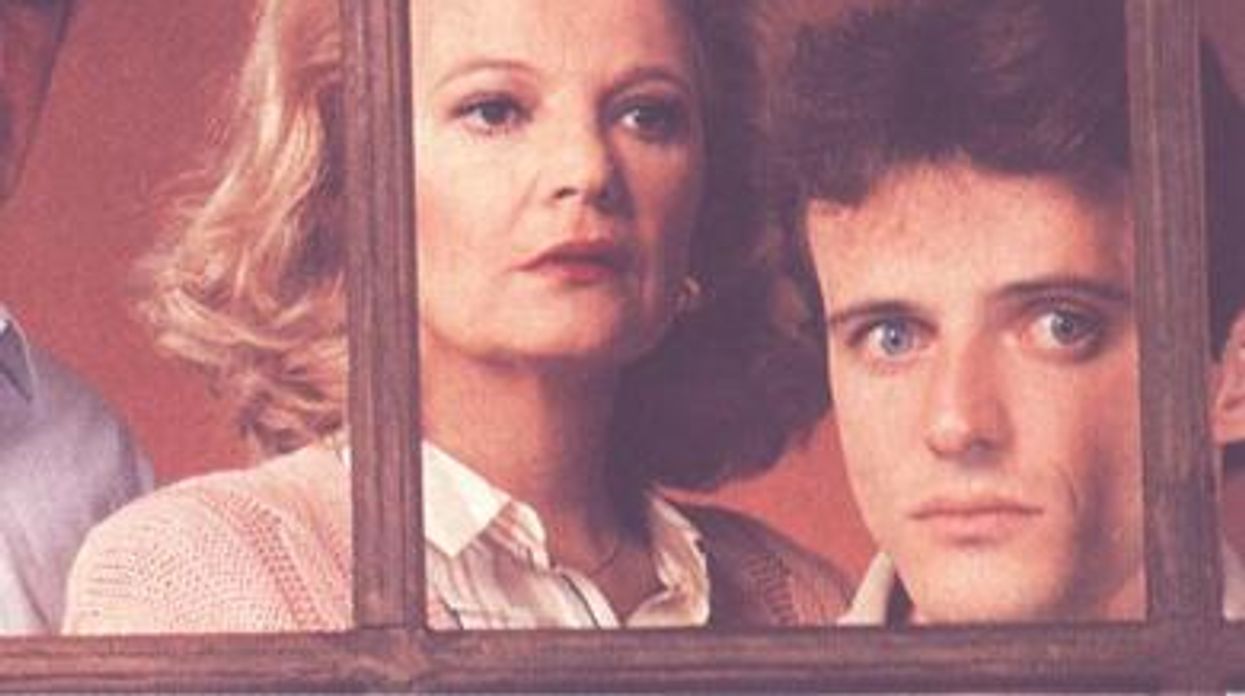

Into this maelstrom of myths and fears came the NBC television movie An Early Frost, broadcast the evening of November 11, 1985. Michael Pierson (Aidan Quinn) is a successful Chicago lawyer who strives to keep colleagues in the dark about his lover, Peter (D.W. Moffett). When Pierson is stricken with a series of illnesses, he learns he is HIV-positive. He returns home, where his mother (Gena Rowlands), father (Ben Gazzara), and grandmother (Sylvia Sidney) must deal with the dual revelation that their son is gay and has a terminal disease.

Frost was far grittier than the typical "disease of the week" films; while acknowledging homophobia, the film imparts basic medical information (stressing that HIV is not transmitted by casual contact) and makes a plea for compassion toward all those infected and affected. (The screenplay was written by Ron Cowen and Daniel Lipman, later creators of Showtime's Queer as Folk.) An Early Frost moved public debate on the disease forward and was nominated for 14 Emmy awards.

When he learned of the project, the Chicago-based Aidan Quinn had just drawn attention for Desperately Seeking Susan opposite Rosanna Arquette and Madonna. His agent told him about the role that several seasoned actors had turned down -- among them, Jeff Daniels, who had played Richard Thomas's lover in Lanford Wilson's Fifth of July.

Quinn had no qualms about playing a man with AIDS for several reasons. "You go with the best stories out there and the best journey you want to take," he says. Coming from the theater, Quinn added, he knew people affected very early in the epidemic. Finally, he was eager to play opposite acting heavyweights Rowlands, Gazzara, and Sidney.

There was no dissent from management or friends, he says: "Because I wouldn't surround myself with people that would say something like that to me. And even if they thought it, they wouldn't say it."

Director John Erman had been directing episodic television since the 1960s (My Favorite Martian, The Outer Limits) but had achieved acclaim for the 1977 TV miniseries Roots and 1983's Who Will Love My Children? with Ann-Margret. The producers had hoped to woo Paul Newman for Frost, but Erman's agent told them, "Paul Newman isn't going to do this; why don't you hire my client John Erman? He's talented, he happens to be a gay man, and I think he has the sensibility to make this movie."

From the start, Erman had to wrangle with nervous NBC executives. They wanted a dream cast to disarm controversy: Elizabeth Taylor or Audrey Hepburn as the mother, Gregory Peck as the father, and Helen Hayes as the grandmother. "'This is not the story of an American family if you're going to cast it this way,'" Erman says he told the top brass. "'This is a Hollywood version of an American family, and I don't think it's the right way to go.' It was a huge fight, because they were terrified to make this film."

Coming east to continue casting the movie, Erman had Quinn read for the role of Michael Pierson. He immediately knew he had his lead. "I loved that he was a really nice guy -- not a prototypical, old-fashioned, matinee idol kind of guy -- who seemed to have a kind of integrity that I felt was really important."

Quinn, in turn, praises Erman's directorial style. "He's really, really supportive," Quinn says. "I really felt -- I don't know how to say it -- it was like he was completely for me and loved me."

As gay men who were suffering numerous personal losses in the epidemic, Erman and cowriters Cowen and Lipman insisted on scientific authenticity in the film script. A medical specialist was hired. Erman brought Quinn to hospitals to meet AIDS patients. On one occasion the two attended a therapy group for people with AIDS.

"And I'll never forget laughing," Quinn says. "The amount [of black humor] that came out of those sessions. And the amount of soulfulness. And I thought, my God, these men -- they were primarily young men -- had wisdom way beyond their years about life because of the situations they were in."

"That was a terrible night because there were so many guys who were practically gone," Erman says. "It was just people talking about their feelings and what they were going through, what their fears were." The pair also visited a man in a New York hospital who shared his thoughts with Quinn on coping with AIDS. The next day Erman received a call: The man had died later that night.

One effort to establish medical authenticity brought unexpected results. In order to understand his character fully, Quinn underwent a typical examination given to someone suspected of HIV infection. The doctor noted that the actor's lymph glands were swollen and his white blood cells elevated.

"And I thought, Jesus Christ! Do I have AIDS?" Quinn says. "Is this some bizarre trick of fate that here I am doing this groundbreaking thing and I actually have it myself?"

The actor lived through a couple of days of mental agony -- "I was kind of freaking out" -- before his HIV antibody test came back negative.

The filming schedule for An Early Frost was short, even by TV movie standards. The 20-day shoot took place mostly in a house in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles. Quinn remembers the camaraderie shared by the actors and crew. Erman echoes that observation: "There was a feeling on that set that we were doing something special."

Erman adds, "The only thing I would say I could compare it to was working on Roots -- because of Alex Haley, we all knew we were doing something special."

However, the filmmakers were dogged by executives from the network's standards and practices division. (The script had already gone through 14 rewrites.) The standards and practices men were always on set. Primarily, they did not want the film to condone homosexuality, a message directly at odds with the director's objectives. Most egregiously, standards and practices wanted the film to depict Peter, who may have inadvertently infected his lover, as a villain. Erman had had enough.

"I said, 'If you persist in this, I will have to take it to the press, because this is just beyond the pale. I wouldn't dream of playing this relationship in anything but a positive way.'" The executives backed off on that matter, but remained on set to ensure there was no physical contact between Quinn and Moffett.

The director calls the production "a smooth-sailing ship" but adds, "It was not a ship that had a million laughs in it. It was emotionally fraught every day, in one way or another." At one point during the shoot, director of photography Woody Omens told Erman with concern, "Every time I look at you, you're in tears."

Erman was guided through the filming by a personal mantra. "I figured out in my head that I was making that movie for my Aunt Myrtle," he says, alluding to his working-class aunt from Chicago. "I thought, I want to make this movie so that she will realize that gay people are just as good as anybody else."

When the finished product was ready to screen for NBC suits, Erman steeled himself. But Steve White, the head of movies at NBC, said, "Don't anybody touch this. It's fine just the way it is. Leave it alone." However, An Early Frost now faced a less receptive industry. Top advertisers refused to buy airtime. Producer Perry Lafferty, an NBC vice president, estimated a half-million-dollar loss in ad revenues.

In that era networks held screenings on both coasts and flew in TV critics from across the country. Erman recalled the New York junket, where reporter questions turned nasty. But Sylvia Sidney stood up and said, "Look, I've been in the business a very long time and there are not a lot of projects that I'm proud to have been involved with, but this is one of them. And this is a wonderful movie and you people don't know what you're talking about."

When the film aired that November evening, apparently curiosity trumped fear and revulsion; An Early Frost drew one third of the night's TV audience, exceeding viewers for ABC's Monday Night Football. The film would garner critical praise and an unprecedented 14 Emmy nominations. Erman was honored by the Directors Guild of America

Aidan Quinn appeared on the cover of People magazine, only to have rumors fly that he actually had contracted HIV and died. "And there was this flurry from long-lost people I had never heard from in so long," he says, "from high school and old agents calling me and my current agent."

At the 1986 Emmy Awards, the cast and crew of An Early Frost sat together and watched 10 out of 14 statuettes go to others. (The film won for sound mixing, editing, cinematography, and outstanding writing in a miniseries or special.)

"In retrospect. I just don't think the Hollywood community was ready for it," Erman says. "It was too soon. We all knew we should have won. We all went out afterwards and got drunk."

Though he received a nomination as best actor, Quinn said his role as Pierson "didn't translate into being an A-list [actor] or being considered for top-notch projects in leading roles. At all. And I thought it would help." Nonetheless, An Early Frost still brings Quinn public praise a quarter century later.

"Someone will approach me and grab my hand and say, 'Thank you for doing it,'" he says. "'You don't know how much that meant to me and my family or helped me come out' or whatever."

John Erman went on to direct more television films and would revisit the theme of AIDS again, in 1991's Our Sons, starring Ann-Margret and Julie Andrews, and 2004's The Blackwater Lightship, with Angela Lansbury and Dianne Wiest. Yet An Early Frost stands as a career turning point.

"Once I finished that movie and once the movie was received the way it was eventually received, I realize that I always had to follow my instincts," Erman says.

Quinn cites Frost as his most socially important work: "That's so rare that you can do a film that actually does make a difference."

The Epidemic in the American Living Room: AIDS and Television

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes