Opening night of

Terrence McNally's Corpus Christi at the

Rattlestick Theater in New York was a benefit for the

Matthew Shepard Foundation and a perfect reflection of how

prophetic the 1998 play really was. The show portrays

Jesus (or, as he is sometimes called, Joshua) as a

young persecuted gay man who's eventually executed

-- strung up -- much as Shepard was 10 years ago in Wyoming

(he died the day before the play's world premiere).

But before that climactic scene, Jesus presides over a

gay marriage of two of his disciples. And when asked

about Leviticus's oft-quoted statement that two men

lying together is an abomination, he simply asks,

"Why would you choose to memorize such a nasty

passage?" While gay marriage and reclamation of

religion were the stuff of fantasy back then --

Corpus Christi is all the more poignant

today because we've seen so much of it come to

pass.

The play

dramatizes classic biblical stories, but McNally

incorporates fresh twists to them with references to

television, the paparazzi, and football. The main

character, Joshua, is a sexually confused young man

from Corpus Christi, Texas, who gets picked on a lot and

molested by priests. He tries to date girls until he

meets Judas, who helps him defeat the bullies and

becomes his high school love. Years later, the two

meet again as Joshua is accumulating his disciples, all gay

men. Their love story threads the play together and

makes the inevitable ending all the more difficult.

(Mary Magdalene is not in this production, but there

is still a prostitute character.) McNally turned one of the

oldest stories ever told into a tale of tragic

romance.

Corpus Christi first premiered amid a great

deal of controversy. The religious right was in an uproar. A

fatwa was declared on the play. The show seems tame by

today's standards -- there is, however, a scene

in which Judas and Joshua make love (fully clothed)

and others in which a male prostitute bares his penis

(obscured) and moons the audience. But the idea that

Jesus could be a gay man and that being gay enabled

his understanding of tolerance and love blew more than

a few minds in its time.

The theater

troupe 108 Productions has been performing Corpus

Christi, directed by Nic Arnzen, around the world

for more than two years. But the group arrived in New York

for the first time Sunday, the night before the show

opened at Rattlestick. With no patron and no stage,

the troupe meets sporadically in Los Angeles

"at whomever is willing to have the group over to

their house," says Steve Callahan, who plays

Judas. The troupe includes women, so many of the

characters didn't register as gay men as they did in

McNally's original version. But the performance

was full of life, helped in no small part by the

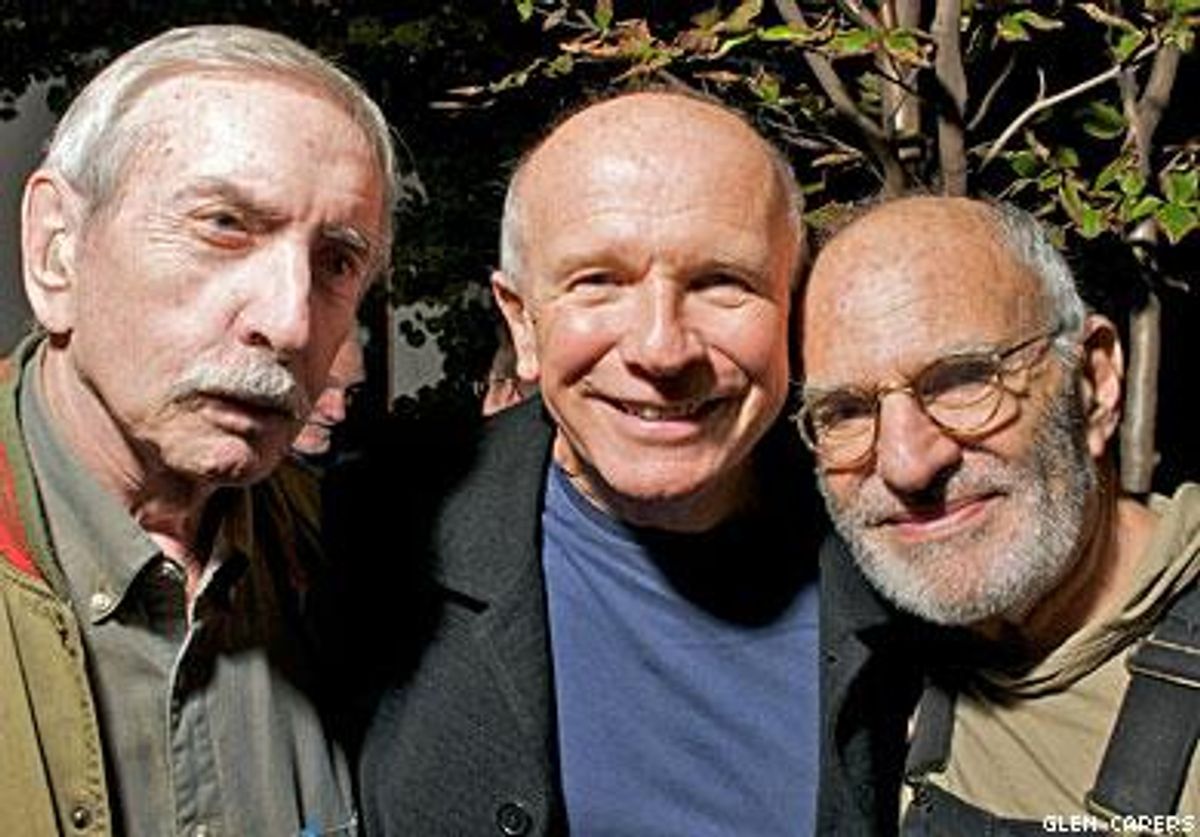

audience, which included McNally, Edward Albee, and

Larry Kramer among others.

The show opens

with the group milling on stage, hugging each other, and

talking as if they're at the start of an AA meeting.

They eventually change, onstage, from their street

clothes to a uniform of khaki pants and white shirts.

And while the this Godspell-like beginning

(people putting on a play about Jesus Christ) seems staged

and the camaraderie forced, once you realize the

troupe has been together for so long, the interaction

seems genuine. Everyone ends up playing multiple parts

(except James Brandon, who plays Joshua), weaving seamlessly

into and out of character with the help of minor

costume and lighting changes and fantastic

choreography that reconfigures the group from cars on a

highway to a field of serpents in the blink of an eye. The

stage is bare except for a couple of benches and a few

props, and the actors keep the audience engaged with

nothing more than their talent.

The performances

are remarkable, however. Molly O'Leary, who plays

Thomas, really chews the scenery -- there's even a

line in the play warning us that she will do just

that. She owns all the comedic moments in the play.

But the real standout is Brandon as Joshua. His embodies the

original message of Jesus with so much charisma that you

believe it actually may be possible to love your

fellow man no matter what. His torment is palpable,

and when he is crucified and the actors (now out of

character) take him down, Brandon is a mess. Switching out

of his character and back into the real world, he can

barely keep it together as the cast members help him

into his jeans. This is perhaps the revival's

greatest success. How hard it must be to get an audience to

become emotionally involved with a story

they've seen performed in innumerable ways. But

watching this cast go from being as excited as a kid on

Christmas about playing these parts to being inconsolable is

undeniably moving.