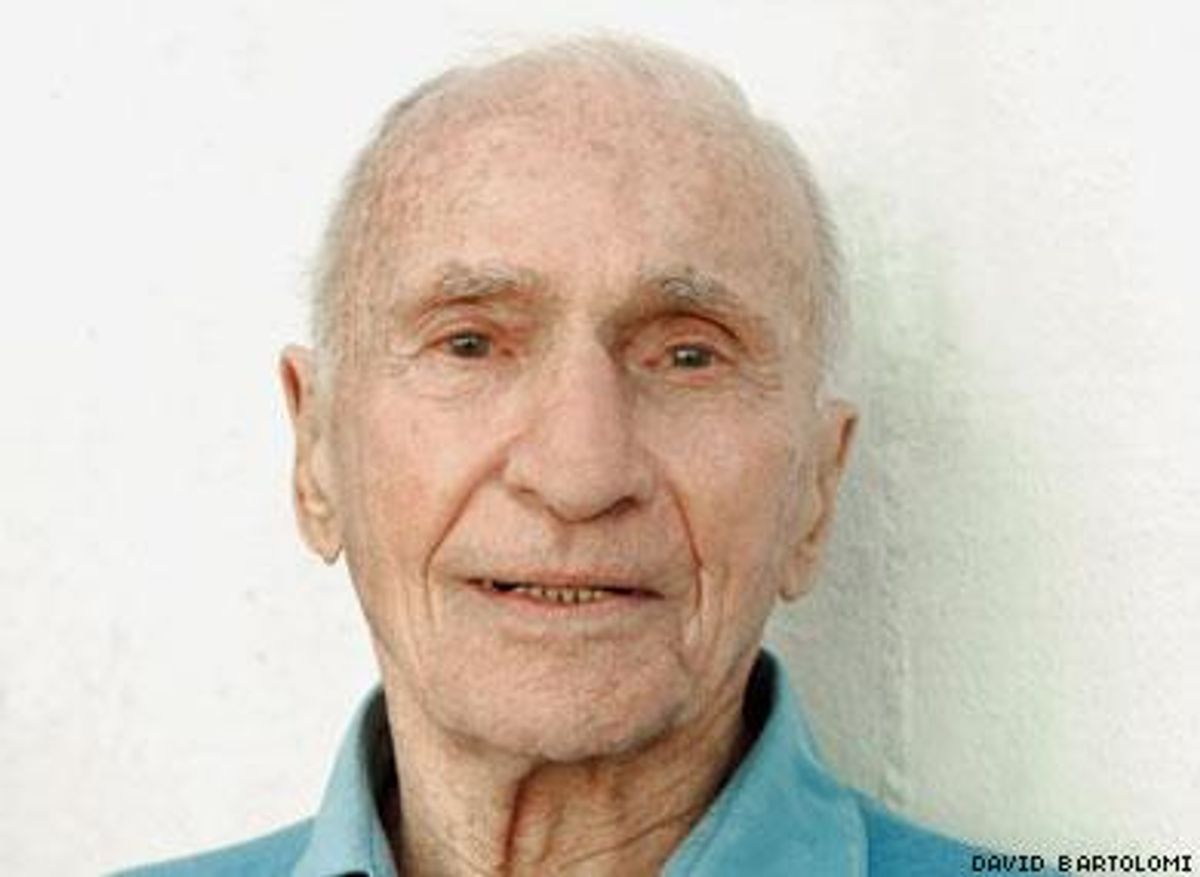

Here's a typical year in the life of Arthur Laurents:

After directing Patti LuPone on Broadway in what was widely hailed as the greatest Gypsy of all time, he immediately started to work on a new, bilingual West Side Story. When it opened, John Lahr wrote in The New Yorker that this West Side is "so exciting it makes you ache with pleasure." In his spare moments he finished his second memoir, Mainly on Directing: Gypsy, West Side Story, and Other Musicals, and completed another new play, New Year's Eve, which opened at the George Street Playhouse in New Jersey less than a month after his new West Side Story made its Broadway debut.

This would be a stupendous degree of productivity for anyone in his 30s or 40s.

But here's the thing: Arthur Laurents is 91.

New Year's Eve is about the ambiguous sexuality of married people and features a married man (played by Keith Carradine) who has an affair late in life with his accountant (Peter Frechette). During an early reading of the play before Broadway glitterati, Laurents realized that the equivocal lives of several of the couples in the audience had been replicated in his play. "It didn't occur to me that one didn't mention these things," Laurents told me. At the end of the reading, Mike Nichols turned to Laurents and declared, "You're the only honest man in New York."

In real life that compulsive honesty has led to some famous blowups between Laurents and everyone from lifelong collaborator Stephen Sondheim (they're barely speaking at the moment) to fellow playwright Larry Kramer (they don't speak at all). When a writer for New York magazine called Laurents's former longtime friend Mary Rodgers to interview her for a profile of the playwright, she was still so angry at him for something he had said to her at a dinner party years ago, her only comment was "Call me back when he's dead."

Last spring Laurents shocked his interviewer on CBS's Sunday Morning by declaring that Katharine Hepburn "had no sense of humor."

"Well," Laurents says to me, "What do you want me to say? 'Kay is a lovely woman, but I think sometimes she doesn't get the joke?' It takes too long."

But when I sat down to talk with him a few days after West Side 's triumphant opening, I found a much mellower version of the man who used to brag to me about how he had made Patti LuPone cry the first time they had lunch together to talk about whether she could play in Gypsy .

In a career that has spanned seven decades, Laurents has written more than two dozen plays and movies, ranging from Rope for Alfred Hitchcock in 1948 to The Way We Were with Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand in 1973. In 1983 he directed the smash-hit Broadway debut of La Cage aux Folles, which won six Tonys, and in 1999 he began a collaboration with David Saint of the George Street Playhouse, where a half dozen of his plays have been produced.

Entering his 10th decade hasn't done anything to slow him down. But when Tom Hatcher, his partner of 52 years, died of lung cancer 2 1/2 years ago, it was a gigantic blow. In the wake of that loss, there is a kinder, gentler Arthur Laurents than most people have known.

Hatcher was an actor working in a men's clothing store when the two of them met in Hollywood in the early 1950s. When they moved in together a few months later, they never made any effort to hide their relationship from their friends, a remarkable thing for a gay couple to do in 1950s America. "When Tom came to live with me, we could have been secretive about it, and we weren't," Laurents says. "It didn't occur to us to pretend otherwise. Tom said when he knew he was gay, he knew he had to get out of Oklahoma. But after that, he wasn't going to make an effort to disguise who he really was."

Laurents was also unusually comfortable with his sexuality, partly because of a remarkable psychiatrist named Judd Marmor, whom he had started seeing in 1947. He recounted for me his first meeting with the doctor:

"Why are you here?" Marmor asked.

"I'm afraid I'm a homosexual," Laurents replied.

"So?"

"What do you mean, 'So?' You know it's dirty and disgusting."

"I don't know anything about it," Marmor said. "All I know is whoever or whatever you are, if you lead your life with pride and dignity, that's all that matters."

"I was terribly moved," Laurents says today, "because it went deeper than just being gay -- what he said about living your life with pride and dignity." By the time he and Hatcher moved in together, Marmor "had done such a good job" on Laurents that he already felt more comfortable with himself than most of his gay contemporaries did.

"Tom was 12 years younger and about a hundred years smarter and wiser," Laurents says. "Because he came from Oklahoma, he wasn't encumbered by all this big-city smartass wisdom. People don't believe this, but what attracted me to him was the thing that is always the most attractive thing about people to me: It's what I consider the pure in heart. And he was."

Nevertheless, he and Hatcher "didn't go around wearing tutus," and Laurents wasn't publicly identified as gay until Frank Rich accidentally outed him in 1995, when he described him in The New York Times as "the liberal, gay Mr. Laurents" after Rich had interviewed him onstage at a theater in Seattle.

"During the interview, Frank talked about Tom as my 'partner,'E,f;" Laurents says. "I'd never heard that word before. And I said, 'Oh, is that what he is?' I thought and still think it's a very odd word. To me, it's someone who sits on the other side of a desk, not in your bed."

But Laurents didn't care in the least that his nonsecret had finally appeared in print. In fact, he says, he can only remember two occasions in his whole life when anyone said anything homophobic in his presence. The first time was when the writer Paddy Chayefsky asked him to go for a walk with him in the '60s.

"I remember we walked through Central Park chatting, and he said he wanted to do a play about the [Communist] witch hunt in Hollywood. He knew I'd survived it and he wanted to know how it had affected 'all the fags.' And I'm walking there saying, 'Uh-huh. So I'm a fag, thank you.' Then he said, 'I wanted to know how much pressure you were in from the witch hunt because you were a fag.' So I said, 'Well, actually, none.' And it's true; I never felt any pressure for being gay."

In fact, he says, "the only time it really came up was when I wrote The Way We Were. " That's when, he says, the movie's director, Sydney Pollack, told him that "everybody in Hollywood is just so surprised." Then, as Laurents remembers:

I asked, "Why?"

"This is the best love story anybody has written in years," Pollack said, "and you wrote it."

"Why are they surprised?"

"Because you're a homosexual."

Laurents was too shocked to respond. "I just thought, You're such an asshole. What can I say? "

Broadway, of course, has long been one of the most gay-friendly places to work in America, and it's there where Laurents is most completely at home. He says he never felt the need to conceal his sexuality from his colleagues, and today, he doesn't think anyone else needs to either -- with one exception. "The only [reasonable] argument I've heard" against coming out is that it could "harm a young leading man," Laurents says. "And my personal opinion is yes, certainly with films, I think it does matter. It's the culture. To me, times have changed most for the Jews. Next for the blacks -- Obama's in the White House, but don't think there isn't an enormous amount of racial prejudice. And finally comes the gays, and I think that will be the hardest. Everybody needs somebody to look down on. And the blacks really look down on gays."

His new book, Mainly on Directing, is very specific about the surprisingly simple secret that made the recent revivals of Gypsy and West Side Story more powerful than all the previous productions of these plays: He decided to put just as much emphasis on acting as all of his predecessors had on singing and dancing.

His first book, Original Story by Arthur Laurents: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood, published in 2000, was equally revealing -- for instance, discussing his affairs with actors like Farley Granger. Mainly on Directing focuses on his love affair with the theater, his love affair with Tom, and the platonic affairs he seems to have had with nearly all of the actors he's ever worked with.

In his latest book Laurents praises Matt Cavenaugh, the actor who plays Tony in the new West Side Story, for "a depth and passion I suspect he didn't know he had, that exploded during rehearsals." Laurents also tells me, "Matt hits notes Larry Kert couldn't," referring to the actor who originated the role of Tony 50 years ago. "I really love him," Laurents says. "He's a lovely guy. I had to unlock him. You know, he comes from Arkansas, and he's basically very conventional. I had to get him to break through himself."

The admiration is mutual. "What is really great about Arthur is that he has such a vast understanding of humanity and human interaction," Cavenaugh says. "He really cuts to the core, which is very advantageous in a piece like this, when so much of it depends on the emotion underneath. Arthur's great about really wanting to know, Who are you? What unique gifts and traits do you bring to this Tony? He was really terrific about freeing us up from any preconceived ideas that might limit us."

Cavenaugh and Laurents love to meet for dinner at an Italian restaurant in the New York City theater district called Trattoria Trecolori. "Arthur loved the veal there," Cavenaugh says. "So for my opening night present I got him a crystal wineglass engraved with these words: 'To finding each otheraEUR|and veal.' (When I mention this to Laurents, he says, "I'll have to find that glass! It never reached me.")

Cavenaugh and Laurents are equally enthralled with Cavenaugh's costar, Josefina Scaglione, the 21-year-old Argentine opera singer Laurents found to play Maria. "I'm completely in love with her," Cavenaugh says, "and those feelings translate into extraordinary chemistry between us onstage. My performance is really based on her Maria."

Scaglione says that before leaving Argentina, she was warned that her future director had a fearsome reputation. "You're going to face Arthur Laurents; that's going to be hard," she was told by friends in the theater there. But Laurents put her at ease as soon as they met, she says.

"I think he felt that I wasn't afraid of anything that people had said about him," Scaglione says. "I think that's why he loved me, and I love him so much. I was overwhelmed and surprised because he had so much energy. He is strict with things he says, and I think that's what makes him a great director. When he has something to tell you he won't hesitate -- he's completely honest."

Laurents says the fearful reputation he has from past blowups always helps him when he directs a new cast. "It works wonderfully because they're expecting something they don't get," he says. Instead of the angry oppressor of Broadway legend, the man his actors see is always the most supportive person on the set.

So what is it that keeps the 91-year-old going like he's still 35? Well, there are some daily vitamins, plenty of fish oil, a couple of weeks of skiing in the winter, swimming almost every day on Long Island in the summer, and nine minutes of floor exercises every morning. And, of course, a still very active sex life: "God knows, I'm all for fucking," Laurents says without a trace of irony.

His doctor told him recently he was going to have "a long life," to which Laurents naturally replied, "What do you think this is?"

But the doctor said, "No, I mean really long," because of his genes and because of what lies at the very foundation of his life: "Your creative juices are still flowing, you keep doing what you like doing, and that affects every organ of the body." Which means we can probably expect to see him directing a 60th anniversary production of West Side Story, right around his 100th birthday.