For my last column I took advantage of summer's slowest stretch to casually sift through gay highlights of the New York International Fringe Festival. But with the busy new 2010-2011 theater season now in full swing, it's time to get about as serious as an aging Victorian prostitute reading The Great Gatsby. Aside from stopping by the first six Broadway shows of the season -- Mrs. Warren's Profession, Brief Encounter, Time Stands Still, The Pitmen Painters, A Life in the Theatre, and Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson -- I also discovered some divine gay characters off-Broadway where least expected.

"Imagine being gay in the 1930s, and you begin to understand Brief Encounter," writes Emma Rice in the Playbill's director's notes of her transcendent adaptation of Noel Coward's 1945 film and the 1936 play on which it was based. She's referring to the lies and shame associated with an extramarital affair -- a "tender agony," as Rice puts it, with which Coward was no doubt familiar. Using gorgeous renditions of Coward's songs and imaginatively interactive film projections, this utterly breathtaking hit from London's Kneehigh Theatre, which ends its Broadway encounter December 5 at Studio 54, conveys the couple's unrequited passion through fantasy sequences like crashing waves and chandelier-swinging. My only gripe is that the vaudevillian shenanigans of the railway station refreshment room's daffy denizens often distanced me from the emotion.

He had slaves and slaughtered Native Americans, but if Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre is to be believed, our seventh president was cooler than Obama. If SNL and Spring Awakening overthrew the History Channel, you might get this electrifying emo-rock musical from writer-director Alex Timbers and out composer Michael Friedman. Benjamin Walker, who played gay in The War Boys, bleeds charisma and sex appeal as Jackson, a pouty populist who makes fratty gay jokes and cuts himself to Cher's "Song for the Lonely." Not offensive among the many outrageous anachronisms, Jackson's associates -- particularly out Upright Citizens Brigade regular Jeff Hiller as John Quincy Adams and The Ritz's Lucas Near-Verbrugghe as Martin Van Buren -- are aristocratically effeminate, and Kristine Nielsen stars as a kooky narrator with a lesbian past.

T.R. Knight can often be seen walking around New York holding hands with his honeymoon-period boyfriend. One can now catch the ex-Grey's Anatomy star holding his own -- against costar Patrick Stewart, that is -- in a satisfying revival of David Mamet's 1977 two-hander A Life in the Theatre, which ends January 2 at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre. Stewart, who'll always be Sterling in Jeffrey to me, plays Robert, a magniloquent stage vet, to Knight's newbie, John, in a series of backstage and slapsticky play-within-a-play scenes Robert might describe as "just like a little walnut ... meaty on the inside and tight all around." Robert's barely concealed envy of his young frenemy may or may not be rooted in attraction, but their vaguely homoerotic tension comes to a rather obvious head when John awkwardly fixes Robert's broken zipper with a safety pin.

When George Bernard Shaw's 1893 drama first opened on Broadway in 1905, The New York Times called Mrs. Warren's Profession "revolting, indecent, and nauseating, where it was not boring." Now being revived by Roundabout through November 28 at the American Airlines Theatre, it's mostly just boring. Though the words are amazingly never uttered, it turns out Kitty Warren made her fortune as -- spoiler alert! -- a prostitute turned high-class madam, much to the horror and reluctant admiration of her educated daughter. Director Doug Hughes handles the attractive but dusty revival with Victorian-lady gloves, but it's still a must-see for Miss Cherry Jones, who, with Cockneyed Mae West flair, simply rivets in her two big monologues that defend her sordid career. Gay character actor Edward Hibbert appears in a thankless supporting role.

After a summer hiatus so that Laura Linney could shoot The Big C, Donald Margulies's Time Stands Still returns to Broadway through January 23 at the Cort Theatre. The luminous Linney and Shrek's Brian d'Arcy James star as war journalists and an unstable couple coping with the physical and emotional aftershock of an Iraqi roadside bombing. I found this drama a bit too restrained upon last review, but I'm so glad I returned to check out new cast member Christina Ricci. Ricci replaces Alicia Silverstone as Mandy, a naive party planner dating the couple's older editor, an excellent Eric Bogosian. Compared to the Clueless star's, Ricci's Mandy is both stronger and more sensitive, igniting much-needed fireworks and providing a fine foil for the judgmental intellectuals. Ricci has clearly triumphed over the stage fright she described in our recent Advocate interview.

As I first noted after seeing last season's Mark Rothko play, Red, writing about music might be like dancing about architecture, but talking about art can make for exhilarating theater. Such is sometimes but not always the case with The Pitmen Painters, a British import that dries December 12 at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre. Written by Billy Elliot screenwriter Lee Hall, who also wrote the book and lyrics for its stellar musical adaptation, this witty but weakly sketched bio-drama tells the tale of a group of coal miners in Northern England who take an art appreciation class in 1934, display an uncanny talent for painting, and become novelty darlings of the art scene. It's a fascinating story that I wouldn't buy if it weren't true, but the play, which benefits from overhead projections of the men's colorful canvases, too often feels like a team-taught lecture.

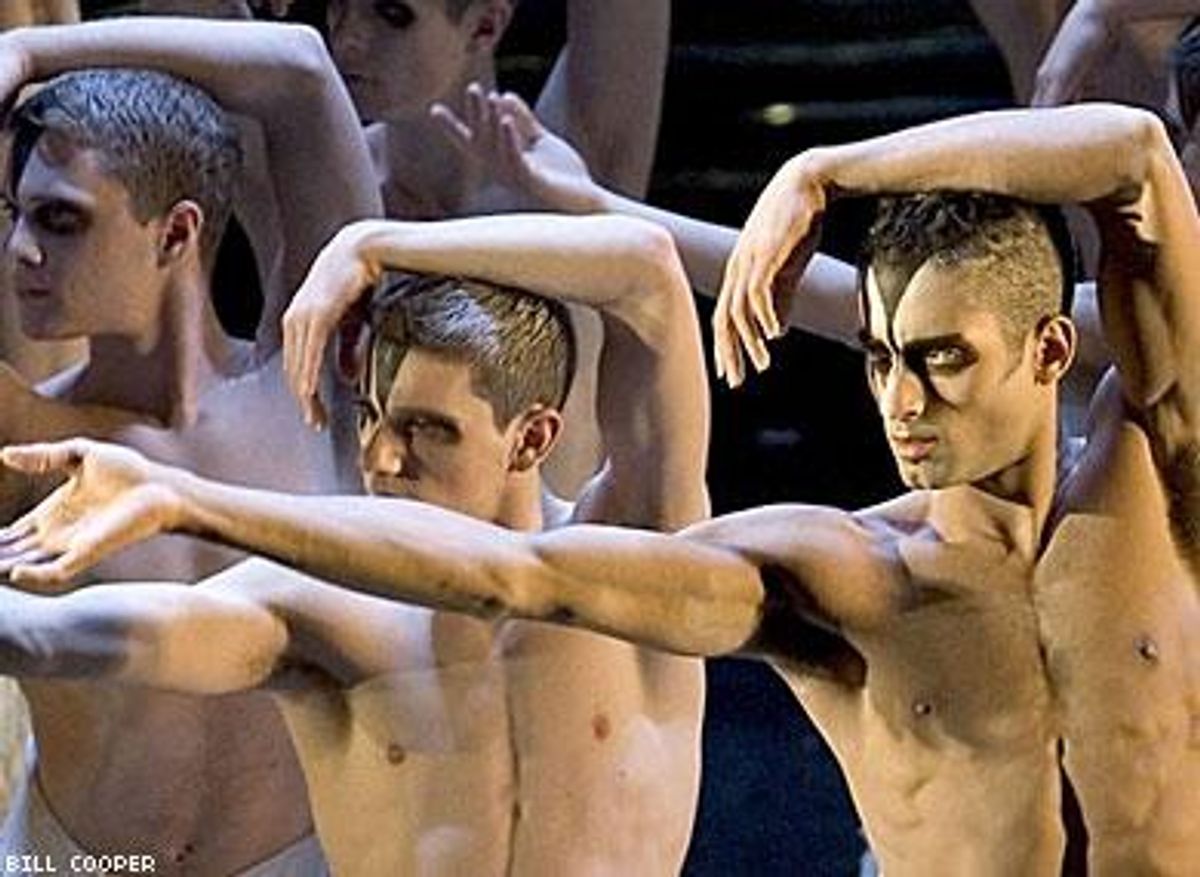

I still recall the review quote on the poster for the 1998 Broadway run of Matthew Bourne's Swan Lake: "See it, or live to regret it." Well, I didn't see it, and I've always regretted it -- until now. A new international tour of the out Brit's acclaimed work, supposedly better than ever, comes to an end at New York City Center, from which it flies November 7. This bold reimagining of Tchaikovsky's classic ballet, which features topless male swans and modern dance styles, ruffled some feathers when it debuted 15 years ago. Today, the story -- an unhappy young prince imagines public scorn and contemplates suicide when he fantasizes about a masculine swan and its human doppleganger -- feels especially topical and poignant. I swooned for the top swan's bitter posse, which includes a clique of sassy swan-twinks who move like they just swam out of a Beyonce video.

Charles Busch had a rare misstep with last year's The Third Story, but I'm happy as hell to report that the legendary drag auteur is back in the old habit with The Divine Sister at the SoHo Playhouse. Directed by frequent gay collaborator Carl Andress, Busch channels Rosalind Russell in The Trouble With Angels and His Girl Friday to play a former crime reporter turned Mother Superior of a struggling Pittsburgh convent in this glorious, deliciously convoluted spoof of wimple flicks like The Singing Nun, The Sound of Music, and even Doubt. "My dear, we are living in a time of great social change," she says. "We must do everything in our power to stop it." There's also a funny bit with Jennifer Van Dyck in boy-drag as a nerdy gay student, plus a brief but bawdy lesbian flirtation between two nuns played by Falsettos' Alison Fraser and Sex and the City's Julie Halston.

Daniel Beaty's Through the Night, which now calls the Union Square Theatre home, is an insightful, hopeful one-man exploration of the African-American male experience. Representing three generations of men who often break out into impassioned spoken-word poetry, Beaty's characters include a recent high school grad, a diabetic preacher, the herbal tea-brewing 10-year-old son of a struggling Harlem health-store owner, and an intravenous-drug user who gave HIV to his pregnant girlfriend: "I'm not on the down low, but I'm lowdown," he says. Beaty -- who counted a memorable gay misfit among the characters in his slavery-themed solo triumph Emergence-SEE! -- shows great humor and heart here as the preacher's son, a music industry exec hiding the real reason he's still unmarried at 40 -- which doesn't exactly go over well with his queeny boyfriend.

Yes, Anthony Rapp is still milking his edge-of-the-millennium claim to fame as an original cast member of Rent, but may all one-man shows be as warmly engaging as Rapp's Without You. Based on his 2006 New York Times best-selling memoir of the same name, this solid, moving exploration of love and loss uses Rent highlights and fine original songs to look back at Rapp's early Rent experience -- including Jonathan Larson's death -- and the fatal illness of his mother, who ultimately makes peace with Rapp's homosexuality. Sold-out and ballyhooed, Without You was a highlight of the seventh annual New York Musical Theatre Festival, which finished October 17 and featured other gay-themed tuners like Our Country, Pandora's Box, My Mother's Lesbian Jewish Wiccan Wedding, Nighttime Traffic, and Oklahomo: The Adventures of Dave and Gary.

Edward Albee squanders a great idea -- a variation on a theme he better explored in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Play About the Baby -- in Me, Myself & I, his 30th play, which runs through October 31 at Playwrights Horizons. An extra-blowsy Elizabeth Ashley stars as Mother, who can't tell apart her identical twin sons, Zachary Booth as cruel OTTO and Preston Sadleir as gentler otto. Then OTTO, who also acts as the play's proscenium-leaning narrator and teases the fact that many identical twins are gay, declares that otto doesn't exist and that his new twin is his mirror image. Oh, brother! Though the play raises lofty questions about identity, individuality, and the split between reality and perception, Albee's wordplay gets tedious, the audience interaction feels desperate, and the lack of evidence to disprove otto's existence is a disappointment.

Subway fares may be rising again, but your bitterness is bound to fade at In Transit, a brisk, crowd-pleasing a cappella chamber musical that screeches to a halt October 30 at 59E59 Theaters. A wise beat-boxing panhandler helps to connect a ragtag group of subterranean commuters like a struggling actress, a broke ex-broker, and a lonely single gal who eats too much pie. Unlike the recent underground tribute Tales from the Tunnel, In Transit shines some daylight on the action, mainly using the subway as a metaphor for getting to a better place in life. With standout numbers "Four Days Home" and "Choosing Not to Know," appealing young tenor Tommar Wilson stars as an African-American gay man who hides his true self on a stressful trip home to Texas and then heartbreakingly contemplates coming out to his religious mom when she visits him in New York.

Until Heather Has Two Mommies or And Tango Makes Three make their way from page to stage, Freckleface Strawberry the Musical might just be the perfect children's show for the R Family Vacations crowd. Based on Julianne Moore's celebrated children's books and featuring a charming cast of mostly 20-somethings, this delightful show by Gary Kupper and Rose Caiola brings to vibrant life the topical tribulations of 7-year-old tomboy Strawberry -- an infectiously spirited Hayley Podschun -- who gets teased by classmates for her red hair and freckles but soon learns to love herself with the help of High School Musical dance moves and catchy songs like "Different," "I Can Be Anything," and "Be Yourself." Slightly subtler is sensitive Jake's boy-crush on sporty Danny, plus bonus nods to iconic Broadway numbers and a Kidz Bop-y Lady Gaga impression.

A.R. Gurney included gay characters in works like Far East, The Old Boy, Big Bill, and, most recently, The Grand Manner. The prolific straight playwright adds a couple more to the mix in Office Hours, which runs through November 7 at the Flea Theater. Written specifically for the Bats, the Flea's talented young acting residents, it's a pleasing if preachy series of vignettes in which junior professors and students discuss Homer, Dante, Aeschylus, Plato, Shakespeare, and other dead white dudes in the Great Books curriculum at a liberal arts college in the '70s. In one of the play's strongest scenes, which all have conflicts that cleverly mirror the classic in question, a flirty gay sex-addict seeks his gay instructor's mentorship to help him stop being a whore -- you know, much in the way St. Augustine describes helping Alypius kick the Colosseum habit in Confessions.

If a six-and-a-half hour reading of F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby in its entirety sounds like a 10th-grade nightmare, skip Gatz. In Elevator Repair Service's four-act epic, which has extended through November 28 at the Public Theater, an employee in a random low-rent office starts to read a copy of the arguably homoerotic 1925 novel. Gradually, his coworkers inexplicably begin to mirror the novel's plot until they're embodying the parts in period costume, which makes for an exhilaratingly bizarre first act. But three breaks and two numb butt cheeks later, little matched the magic of that initial metamorphosis. I wish my patience had been rewarded with less stagnancy and a clearer connection to the employees, who were intriguing even before channeling Gatsby characters like Jordan, the butch lady golfer, and Nick, the possibly closeted narrator.

In the Next Room's Sarah Ruhl further explored sexuality in her bewitching adaptation of Virginia Woolf's Orlando, a fantastical meditation on the fluidity of gender identity, which closed October 17 at Classic Stage Company. In Woolf's 1928 novel, which is often described as a love letter to cross-dressing author Vita Sackville-West, a young English nobleman inexplicably wakes up one morning as a woman. Taking a cue from the 1993 film starring Tilda Swinton as Orlando and Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth, this play filled those roles with phenomenal androgyne Francesca Faridany and quirky out actor David Greenspan, one of three men in a gender-blurring Greek chorus. Ruhl wisely let Woolf do the talking here, opting for a descriptive third-person narrative in lieu of new dialogue -- a children's-story-theater style befitting a tale full of so much wit and wonder.

The world premiere of The Revival closed September 25 at the Lion Theatre, but if there is a God, it will be made into a movie soon. In this tense, staggering drama by Samuel Brett Williams, which director Michole Biancosino jump-started with a pre-show choir, Trent Dawson of As the World Turns starred as Eli, the son of a Southern Baptist preacher who returns to his Arkansas hometown to rebuild his father's congregation. Pressured to compete with megachurches, the married pastor becomes an overnight evangelical superstar when he publicly "cleanses" a troubled young stranger named Daniel -- an outstanding David Darrow -- of his homosexuality. The twist? Eli and the rough-trade hothead are actually having sex! "It's hot and cold, but good -- hard to explain," says Daniel of the look Eli gave him at the church potluck. "Kinda like makin' meth."

In LGBT journalist Cody Daigle's A Home Across the Ocean, which ended a two-week run October 2 at Theatre Row's Studio Theatre, David Stallings and Mark Emerson skillfully portrayed a young gay couple who take in a foster child, Penny, in hopes of adopting her. But instead of focusing on the sexuality of the prospective parents, Daigle refreshingly prefers to mine drama from the fact that Penny is a painfully distant 13-year-old African-American girl who still dreams about the return of her birth parents. That may sound like the very special pilot episode of an '80s sitcom sandwiched between Webster and Diff'rent Strokes, but it's actually a smart, thoughtful exploration of change, renewal, survival, and the true meaning of family. Its bloated running time could and should be whittled down before its next outing, but this Home is definitely where the heart is.

The out playwright who put a lesbian couple in danger in the thrillingly intense Killers and Other Family, Lucy Thurber almost put me to sleep with the admirably ambitious but awkwardly pretentious Bottom of the World, which closed October 3 at Atlantic Theater Company's Stage 2. Crystal A. Dickinson starred as Abby, a young lesbian made practically unbearable by grief over the death of her novelist sister, Kate, who still hovers above in an huge tree with mood-setting bluegrass musicians. As Abby's issues prove too much for her barfly girlfriend, an oddly alluring K.K. Moggie, Abby and Kate's sisterly bond is shown funhouse-mirrored and gender-switched in sepia-toned scenes ripped from Kate's Our Town-y novel, which features a pair of bed-sharing buddies played by Brandon J. Dirden and Brendan Griffin, a cute ginger who recently played gay in Clybourne Park.

The gayest show I saw last month might have also been the most critically maligned. It Must Be Him, a semiautobiographical comedy by Kenny Solms, a gay cocreator and writer of The Carol Burnett Show, ended its brief run September 26 at the Peter Jay Sharp Theater. Bosom Buddies star Peter Scolari played Louie, a washed-up 55-year-old gay writer so enamored of his hot young muse that he's blind to the affections of his age-appropriate manager. Clinging to an old Emmy and arguing with ghosts of dead parents who still aren't that keen on his sexuality, Louie tries desperately to rekindle his fading career by adapting his life story into an awful movie and worse musical, which features a scandalous number about leather daddies and enormous dildos that makes The Producers' "Springtime for Hitler" look like Seussical. But in this round of the so-bad-it's-good game, bad won.