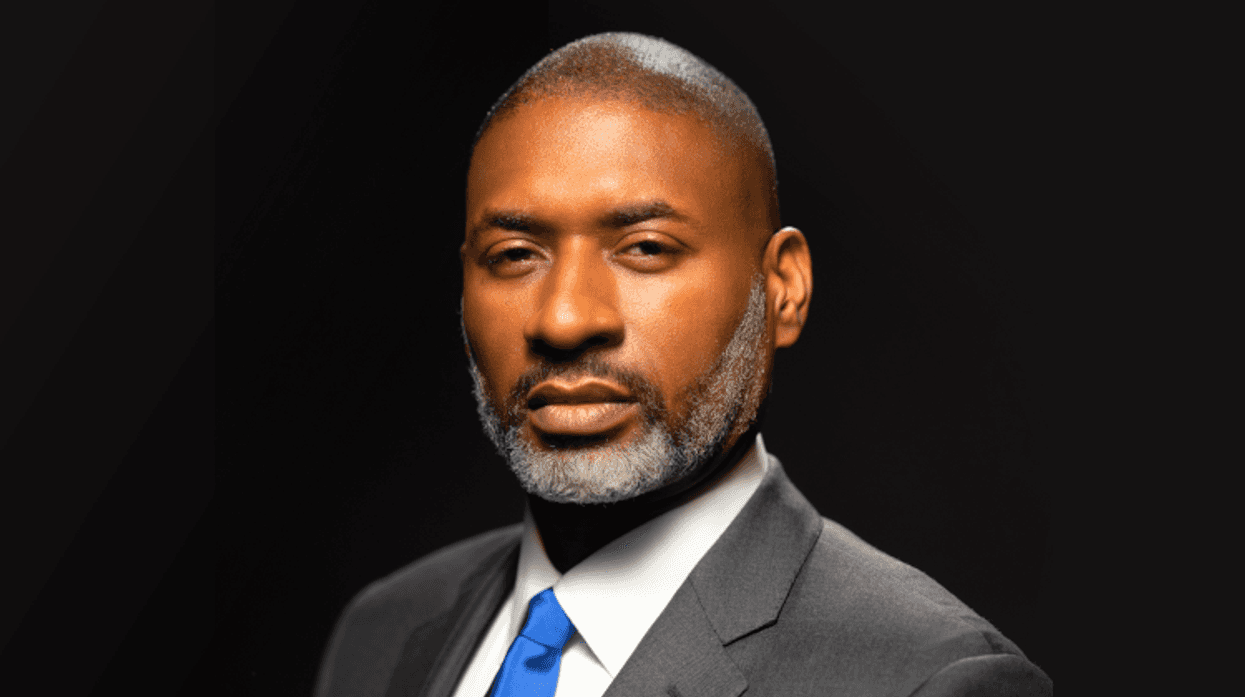

The language of being "out" or "out of the closet" has evolved into something broad and imprecise -- something that looks and feels different for everybody. When Charles M. Blow was married to his ex-wife, she knew he was bisexual. And after their marriage ended, he dated men and women, so while he didn't publicly talk about his sexuality until 2014 when his memoir, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, came out, describing him as having been "in the closet" isn't fully accurate.

Few of us have to contend with the added layer of having to come out publicly. For Blow, it became a necessity when he started writing a column for The New York Times in 2008. "In that very first moment, I knew what that meant, that I was now a public figure," he says. "I knew that from a life in newspapers, that if you tell your own story, it belongs to you. If somebody else tells your story, it belongs to them. And they're not going to be as kind to you as you will be to yourself."

He came out, publicly, and what he found was not a community waiting with open arms to embrace this new, high-profile addition to the fold. Instead, the more common response came in emails, almost always from white gay men, who denied the existence of bisexuality and said things like "Oh, easy to come out now because you are well-off and you are old. I've suffered through this since I was 17..." People were not kind. "The power architecture around queerness has long been dictated by a very narrow band of people, and I wasn't in that. I just wasn't," Blow says.

In more recent years, Blow thinks about the queer elders, both those whose names we know and those we don't, who helped pave the way for him to be out and have the career that he does. "When you are not living an honest, open, true life, you are taking advantage of a privilege granted to you by older gay, lesbian, queer people who have sacrificed tremendously so that you could come into this place. And they did so very often at great costs."

It's a debt he's repaying with his visibility at The New York Times and on the Black News Channel, where he hosts the new nightly news show Prime With Charles Blow. "Part of disclosure helps you pay that debt because you add your visibility."

Charles M. Blow recently spoke with the LGBTQ&A podcast to celebrate the launch of his new talk show. You can read an excerpt below and listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Jeffrey Masters: In your memoir, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, you wrote that while the term bisexual is technically correct for you, you don't embrace the label. You cited it as having "derisive connotations." That was back in 2014. Do you still feel that way about the word?

Charles M. Blow: No, I don't understand why we run away from labels or are worried about labels. It's not a big thing. I'm going to have the life I'm going to have anyway. Whatever you call it is not going to change how I live and how I love a bit. I'm not caught up in the label as much or tied to it. Listen, do whatever you want to do, because I'm going to do what I want to do. I find it is an easy way to describe my attractions.

For all the progress we've made, we've done a poor job at demystifying bisexuality.

Right. The idea of bisexuality, actually, people take as a challenge to absolute binary identities. The idea that someone could be fluid and move in and out of an identity is a challenge to the people who are singularly attracted to men or women. It's an incredible challenge to the binary construct.

And so people want to say, "Well, you must be on the path to something. You're bi now and gay in five years or three years." I understand all those things, but the assumption that if someone tells you that this is their identity and you completely deny that is incredibly offensive because you're basically saying the person is lying.

A large number of gay men came out as bi first, so it's easy for them to think that's how everyone's experience will line up

It's complicated in that way if it's not your life. For me, there's nothing complicated about the way my brain works because that is the way it has always worked. The denial was always trying to be part of a binary, trying to be a part of the straight world or trying to be completely part of the gay world. For a very long time, I didn't even believe that there were completely straight and gay people. I just thought everybody else was hiding it. I could not believe that there was not a single person of the other gender you're not attracted to. How? How is that possible? That's what my brain was doing because my brain was not making the distinction between people. It was, I find these things to be attractive in human beings. And whenever I find it, I like it.

You publicly came out in 2014 with your memoir. Why was that the right time?

Oh, it wasn't the right time. It was that the Times had made me a columnist. In the very first moment, I knew what that meant, that I was now a public figure and not a private figure.

My role model in that is James Baldwin, who talks about why he had been so public about being gay. He said, "That means that you cannot blackmail me." I knew that from a life in newspapers, that if you tell your own story, it belongs to you. If somebody else tells your story, it belongs to them. And they're not going to be as kind to you as you will be to yourself. So it was incumbent upon me to share my life because it's protective.

Up until becoming a public figure, it didn't even feel like it was a secret. When I had gotten married, my ex-wife knew everything about me. I told her literally everything in probably too much detail. But I felt like as long as the person who I had committed myself to love and be in relationship and be in marriage with, as long as I had been completely honest with that person, it was nobody else's business.

Were you avoiding gay bars and queer spaces during that time?

When I was married, I was just monogamous. So yes, I was avoiding gay bars.

What about in 2014 after your divorce and after you'd come out?

In that period, I'd go out to straight bars and I'd go to gay bars. I had girlfriends. I dated guys. It felt like a very natural expression of me. So there's a period in there where I am out and about and people know me. I have friends in all spaces, gay and straight, and yet I am not identifying in any public space as bi or gay or queer or anything. That is a period where you're living a life of a bisexual man, but you haven't said it out loud, publicly. So that is closeted. There's no other way to describe that.

It doesn't feel good. You can rationalize, I don't need to say anything. But it still doesn't quite feel honest, honorable, and brave. So I guess that is another rationale for writing a book. It's just liberating. There's no more worrying. Even when you don't feel like you're completely hiding, there is some part of you that is. If it were not a thing, then everybody would know. All your friends would know. Everybody in your family would know if it was truly not a thing. So the fact that they don't, then that means it's a thing.

Do you feel like you missed out on being young and openly queer?

I don't have regrets about the relationship that I've had and the people I've loved. In my 20s, I was very much in love and I was married and had kids. And I could have had that life for the rest of my life. If that marriage had not stopped, I was perfectly comfortable in it and happy with it.

What I do sometimes think about, though, is when you are not living an honest, open, true life, you are taking advantage of a privilege granted to you by olde, gay, lesbian, queer people who have sacrificed tremendously so that you could come into this place. And they did so very often at great costs. So that felt crappy.

That felt like you're taking advantage of something to which you owe a debt. Part of disclosure helps you pay that debt because you add your visibility. I'm not saying this about the teenager. When you don't have a home to call your own and you don't have a place to go because you have to go to school. I'm not talking about you. I'm talking about the 30-year-old man. I was a 37-year-old man at that time. There was nothing for me to lose, other than the approval of people who didn't really know me because they didn't know that part about me.

That disapproval from other people you mention, it's not significant.

I think you have to weigh the suffocation of your soul against whether or not the approval of other people is more important than that. There's no way for you to live a true life if you're living a lie for them.

At the end of the day, part of my decision was just, I can't even be an honorable man unless I do this. I think of myself as incredibly courageous and brave and nothing can knock me down. And no, I'm not. If I can't do that, then I can't lay claim to any of that bravery or valor. So in order for me to see myself as to be the person that I saw myself as, which is a courageous fighter for the vulnerable, I had to fight for me and say, "To hell with whatever comes of it. You don't want to be part of my life anymore? Fine."

And I had the privilege of doing that because I was older. People like me, in your 40s, what was I waiting for? There is nothing worth slowly killing yourself on the inside, on the weight of a lie. No other person's disapproval could ever compare to your own disapproval of yourself.

You have the added complexity of having three kids. Was that conversation something you worried about having with them?

Not really. They are incredibly egalitarian, really smart, cosmopolitan children. I had a family meeting; they came to the table, I had printed out manuscripts. I said, "I've written this book. This is what's in it." And I gave them all a printed manuscript.

You also disclose sexual assault in the book. Did you give them a heads-up on what they'd find?

Yeah. I said, "I've written a book. This is what's in it." I said, "Read. If there're any questions, let me know."

They were like, "I've also been bullied." That's how their minds work. They were just like, "I can understand that." So that was the way they thought about it. My oldest son, who is the fastest reader in the family, he sat down, he read it all in one sitting. So by the end of the evening, he was finished and he came to me and he says, "I just think you need to develop my mom's character more in that last chapter." It was an editorial note. It wasn't even about the content of it. They are not phased in any way. It's not how they think.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Prime With Charles Blow airs at 10 p.m. Eastern Monday-Friday on the Black News Channel.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Niecy Nash, and Roxane Gay. Episodes are released every Tuesday.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes