Many in the LGBT community think of the Stonewall vets, as some call us, like heroes. For me it started out as a frightening event.

I was in the back of the bar near the dance floor, where the younger people usually hung out. The lights in the room blinked--a signal that there would be a raid--then turned all the way up. Stonewall was filled that night with the usual clientele: drag queens, hustlers, older men who liked younger guys, and stragglers like me--the boy next door who didn't know what he was searching for and felt he had little to offer. That all changed when the police raided the bar. As they always did, they walked in like they owned the place, cocky, assured that they could do and say whatever they wanted and push people around with impunity. We had no idea why they came in, whether or not they'd been paid, wanted more payoffs, or simply wanted to harass the fags that night. One of the policemen came up to me and asked for my ID. I was eighteen, which was the legal drinking age in New York in those days. I rustled through my wallet, very frightened, and quickly handed him my ID. I was no help in their search for underage drinkers. I was relieved to be among the first to get out of the bar.

As a crowd began to assemble, I ran into Marty Robinson who had inducted me into something called "The Action Group," and he asked what was going on.

"It's just another raid," I told him, full of nonchalant sophistication. We walked up and down Christopher Street, and fifteen minutes later we heard loud banging and screaming. The screams were not of fear, but resistance. That was the beginning of the Stonewall riots. It was not the biggest riot ever--it has been tremendously blown out of proportion--but it was still a riot, although one pretty much contained to across the street on Sheridan Square and Seventh Avenue. There were probably only a couple hundred participants; anyone with a decent job or family ran away from that bar as fast as they could to avoid being arrested. Those who remained were the drag queens, hustlers, and runaways and street kids like me.

People had begun to congregate at the door after they left the bar. One of the cops had said something derogatory under his breath and the mood shifted. The crowd began taunting the police. Every time someone came out of the bar, the crowd yelled. A drag queen shouted at the cops: "What's the matter, aren't you getting any at home? I can give you something you'd really love." The cops started to get rough, pushing and shoving. In response the crowd got angry. The cops took refuge inside. The drag queens, loud and boisterous, were throwing everything that wasn't fastened down to the street and a few things that were, like parking meters. Whoever assumes that a swishy queen can't fight should have seen them, makeup dripping and gowns askew, fighting for their home and fiercely proving that no one would take it away from them.

More and more police cars arrived. Some rioters began fire-bombing the place while others fanned out, breaking shop windows on Christopher Street and looting the displays; somebody put a dress on the statue of General Phil Sheridan. There was an odd, celebratory feel to it, the notion that we were finally fighting back and that it felt good. Bodies ricocheted off one another, but there was no fighting in the street. All the anger was directed at the policemen inside the bar. People were actually laughing and dancing out there. According to some accounts, though I did not actually see this, drag queens formed a Rockettes-style chorus line singing, "We are the Stonewall girls / We wear our hair in curls / We wear no underwear / To show our pubic hair." That song and dance later became popular with a gay youth group I was part of, and months after Stonewall, Mark Horn, Jeff Hochhauser, Michael Knowles, Tony Russomanno, and I would dance our way to the Silver Dollar restaurant at the bottom of Christopher Street. We were going to be the first graduating class of gay activists in this country--indeed, most of us are still involved, and we're in touch with each other to this day.

Marty Robinson, after seeing what was happening, disappeared and then reappeared with chalk. Most people don't realize that Stonewall was not simply a one-night occurrence. Marty immediately understood that the Stonewall raid presented a "moment" that could be the catalyst to organize the movement and bring together all the separate groups. He was the one person who saw it then and there as a pivotal point in history. At his direction several of us wrote on walls and on the ground up and down Christopher Street: Meet at Stonewall tomorrow night. It was the only Action The Action Group ever did, but it was pivotal. Of the Action Group, only Michael Lavery and myself survive. Michael went on to be one of the founders of Lambda Legal.

The nights following the Stonewall raid consisted primarily of loosely organized speeches. Various LGBT factions were coming together publicly for the first time, protesting the oppressive treatment of the community. Up until that moment, LGBT people had simply accepted oppression and inequality as their lot in life. That all changed. There was a spirit of rebellion in the air. More than just merely begging to be treated equally, it was time to stand up, stand out, and demand an end to fearful deference. Stonewall would become a four-night event and the most visible symbol of a movement. We united for the first time: lesbian separatists, gay men in fairy communes, people who had been part of other civil rights movements but never thought about one of their own, young gay radicals, hustlers, drag queens, and many like me who knew there was something out there for us, but didn't know what it was. It found us. So, to the NYPD, thank you. Thank you for creating a unified LGBT community and thank you for becoming the focal point for years of oppression that many of us had to suffer growing up. You represented all those groups and individuals that wanted to keep us in our place.

The Action Group, which Marty Robinson headed up eventually joined with other organizations to become the Gay Liberation Front, or GLF. In that first year GLF helped create the new gay movement, along with people like Martha Shelley, Allen Young, Karla Jay, Jim Fouratt, Barbara Love, John O'Brien, Lois Hart, Ralph Hall, Jim Owles, Perry Brass, Bob Kohler, Susan Silverman, Jerry Hoose, Steven Dansky, John Lauritsen, Dan Smith, Ron Auerbacher, Nikos Diaman, Suzanne Bevier, Carl Miller, Earl Galvin, Michael Brown, Arthur Evans, and of course Sylvia Rivera.

Over the last few years, LGBT history has become a passion of mine, and sometimes it seems that the younger generation doesn't really care about it. The Gay Liberation Front has mostly been ignored in the history books, even though it helped forge the foundation upon which our community is built.

Stonewall was a fire in the belly of the equality movement. Even so, accounts of it are full of myth and misinformation, and much of that will inevitably remain so, since there are differing accounts from those active in the movement. That's the nature of memory, I suppose. Regardless of the diverging stories, and no matter how intense the fighting was, Stonewall represented, absolutely, the first time that the LGBT community successfully fought back and forged an organized movement and community. All of us at Stonewall had one thing in common: the oppression of growing up in a world which demanded our silence about who we were and insisted that we simply accept the punishment that society levied for our choices. That silence ended with Stonewall, and those who created the Gay Liberation Front organized and launched a sustainable movement.

But Stonewall was not the first uprising. LGBT history is written, like most history, by the victors, those with the means and those with connections or power. Two similar uprisings before Stonewall have almost been written out of our history: San Francisco's Compton Cafeteria riot in 1966 and the Dewey's sit-in in Philadelphia in 1965. Drag queens and street kids who played a huge role in both events never documented those riots, thus they have been widely eliminated by the white upper middle class, many of whom were ashamed of those elements of our community. But Stonewall, Compton, and Dewey's all have one thing in common: drag queens and street kids. For some historians, drag queens are not the ideal representatives of the LGBT community. Oppression within oppression was and is still of concern. Even recently, with the transgender issue finally being taken seriously, there is still a backlash from the community about including them in the general gay movement.

It has been over forty years since the Gay Liberation Front first took trans seriously, but the gay men who wore those shirts with the polo players or alligator emblems didn't want trans people as the representation of their community. Their revisionist history has been accepted into popular culture because they were the ones with connections to publishers, the influence, as well as the money and time to sit back and write about what "really" happened.

And even before Compton's there were the Dewey's restaurant sit-ins in Philadelphia in April 1965. The restaurant management decided not to serve people who demonstrated "improper behavior." The reality was that they didn't want to serve homosexuals, especially those who didn't wear the acceptable clothing. Meaning drag queens. A spontaneous sit-in occurred and over the next week the Janus Society, an early gay rights organization, had picketers on site handing out flyers. Most were people who had little to lose, the street kids and drag queens once again. Those LGBT people with the little animals on their polo shirts were in short supply.

Both Compton's and Dewey's point to the fact that in the mid-1960s the fight for black civil rights was beginning to influence the more disenfranchised in the gay community. The major difference with those two early events is that from the Stonewall riots grew a new movement, one that still lives today. Nonetheless, they deserve to be remembered.

The biggest fallacy of Stonewall is when people say, "Of course they were upset, Judy Garland was being buried that day." That trivializes what happened and our years of oppression, and is just culturally wrong. Many of us in Stonewall who stayed on Christopher Street and didn't run from the riot that day were people my age. Judy Garland was from the past generation, an old star. Diana Ross, the Beatles, even Barbra Streisand were the icons of our generation. Garland meant a little something to us, as she did for many groups--"Somewhere Over the Rainbow"--but that was it. And, honestly, that song was wishful thinking, an anthem for the older generation. In that bar, we were going to smash that rainbow. We didn't have to go over anything or travel anywhere to get what we wanted. The riot was about the police doing what they constantly did: indiscriminately harassing us. The police represented every institution of America that night: religion, media, medical, legal, and even our families, most of whom had been keeping us in our place. We were tired of it. And as far as we knew, Judy Garland had nothing to do with it.

While I didn't know it at that moment, I was fighting back against feelings that had been suppressed for so many years. It was time for the real thing. As the riot was happening all around me, the idea of a circus came to mind, and then it hit me: we can shout who we are and not be ashamed, we can demand respect. We were fighting for our rights just as women, African Americans, and others had done throughout history.

After my Grandmom had taken me to my first civil rights demonstration at thirteen, I'd watch the news every night, waiting to see the latest update on what was happening. My television viewing and newspaper reading included following the Freedom Riders in the South. The sit-ins and marches had a big impact on me. The images of Birmingham, of Bull Connor with his German shepherds snapping, of the fire hoses blasting people marching for desegregation moved me. They led me to ask how one human could possibly treat another in that manner. I realized, too, the brilliance of Martin Luther King Jr., the Atlanta pastor and face of the movement, in his strategic use of Bull Connor and Birmingham to showcase the hatred behind segregation. What's more, Bayard Rustin, MLK's contemporary in the fight for equality and his chief of staff for the March on Washington, was a gay man, vocal on the rights of gay people. The FBI and others tried to use Rustin's "homosexuality" against him, and some of the organizers of the march wanted to drop him, but MLK stood tall in supporting him. It wouldn't be until I interviewed Coretta Scott King in 1986 and she reaffirmed her husband's support of "gay rights" that I got to personally offer my gratitude. It was an unknown fact to many, including those of us in Gay Liberation Front, which would become the only university I ever attended.

Gay Liberation Front, in all likelihood, was the most dysfunctional LGBT organization that ever existed, which shouldn't be very surprising. Born from the ashes of the Stonewall riots, it brought together for the first time the various elements and fractions of the community, to organize, to strategize, and to fight back. Before Stonewall we were polite; after Stonewall we demanded our equality. To that point we had no understanding of who we were as a people, we only had what society told us we were, and at that time a lot of us in New York were attempting to redefine ourselves. There were many individuals who began to set up collectives, lesbian separatist groups, discussion groups, even communes, and everything in between.

In addition to redefining ourselves, we also realized from the beginning that we were focused on building a community, since we couldn't count on any part of society to provide the basic services we needed. We had to create those institutions where they had never existed before. We were trying to establish our goals and figure out what kind of organization we would be. Since we were oppressed by the system, we didn't want to use any of their old tools in our meetings.

Therefore, there was no leadership at GLF, no permanent chair, only the occasional use of Robert's Rules of Order. Decisions were made by consensus, and in order to reach that point some meetings went late into the evening. It was total chaos. It worked, but at times it was almost comedic.

At one meeting a woman spoke about how men were trying to control women in the organization. Her example was that the men with beards in the group did not understand how through the ages facial hair had been used to symbolize the dominant male of a community, i.e., the leader. So men with beards at Gay Liberation Front were supporting the oppression of women. The following week several men, in order to show solidarity, came to the meeting with their beards shaved. That upset some of the other men, who saw beards as fashion or a symbol of who they were, accepting their masculinity. That in turn upset the fairies who wanted men to accept their feminine side. And around it went.

We debated everything, with the exception of creating community--we were all agreed on that goal, and worked to form groups to help us achieve it. There was no debate when I advocated for a gay youth group and little debate when Sylvia Rivera created Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), one of the first-ever trans organizations. There was no debate on health alerts, and the only conflict about opening the first LGBT community center in the nation related to money, not the idea. This is part of why 1969 is often cited as the start of the new gay rights movement. Gay Liberation Front led our struggle from a mere movement trying to change laws into one of harvesting community.

We were so radical that even Harvey Milk, the "Mayor of Castro Street" who lived in New York before he became the first elected openly gay member of San Francisco's Board of Supervisors in 1977 and was assassinated in 1978, stayed clear of us.

Little known fact about Harvey: His former partner and later a friend of mine was Craig Rodwell, founder of the Oscar Wilde Bookshop. He was also the founder of what today is Gay Pride Day, but what Craig then called the Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day. Milk was so closeted in 1970 that he wouldn't involve himself with the event or any other gay movement. He only did so after moving away from his New York family to San Francisco in 1972 For those who appreciate LGBT history, the first openly gay or lesbian elected official anywhere in the country was Nancy Wechsler, voted to the city council in Ann Arbor in 1972, then Elaine Noble to the state house in Massachusetts in 1974. It would not be until 1987, when Barney Frank came out, that we would have an out member of Congress, and 2012 when we finally had an out member of the US Senate, Tammy Baldwin.)

Like all caucuses, committees, cells, or communes, each group within the Gay Liberation Front had its mission. While I didn't form the first youth group, I organized the first one intended to be a foundation on which a community could then be built. We were going to reach out beyond the areas where LGBT youth were thought to be. We took on the serious issues of bullied, battered, homeless, and suicidal gay youth. We created safe spaces and safe activities. And not only were we there to offer our support to one of the most endangered segments of our community, we were there to nurture future activists. We were in some ways the first graduating class of gay liberation. Donn Teal wrote in The Gay Militants: "As GLF had given birth to organizations for transvestites and transsexuals and for Third World people, so did it sire Gay Youth." Published in 1971, this was the first LGBT history of those early years.

Our flyers clearly stated that our goals were both political and social. We even surprised our older comrades in the Gay Liberation Front with our media outreach directed at gay youth. We went on radio talk shows and even TV shows. We spoke at high schools. One of my favorite items of that time was a copy of the Spider Press, the newspaper of Oceanside High School, and there on the cover is a picture of Gay Youth members Tony Russomanno and Mark Segal with the headline, "Gay Activist Lecture; They Are Not Neurotic." This was October 23, 1970.

I hosted movie nights in my five-story walk-up apartment on 12th Street and Avenue C, which was a three-room tenement decorated with donations and furnishings from the street; the bathtub was in the kitchen. It had a nice living room where we would plug in the borrowed projector and show films on the wall, before leaving to take a walk across town to Christopher Street. These movie nights grew too popular for the apartment so we moved them to Alternate U, where we held our dances. Gay Youth did all of this with no real funding, with the exception of what came from our pockets or what we received from the small Gay Liberation Front treasury.

As Marc Stein writes in his book Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement, "Interest was so great among young people that in 1970 GLF-NY established a Gay Youth caucus . . . Led by Mark Segal, Gay Youth soon was functioning as an autonomous organization with affiliated groups elsewhere in the United States and Canada." For me, Gay Youth was a lesson in both creating lifelong friendships and leadership. It also helped me prove to myself that my career as an activist was real--as long as I had no expectations of a salary.

The most contested topic at any Gay Liberation Front meeting was sexism, but we debated many subjects. At times the debates became personal and it was not unusual to hear people being labeled capitalist pigs, fascist, racist, sexist, and for good measure I'd even toss in the label ageist on occasion.

Somehow even the simple act of a kiss took on political overtones. Perry Brass tells this story: "Someone explained to me that these were 'political kisses,' to show that we were out and proud, especially at a GLF meeting. At my first meeting we broke into discussion groups after the 'business' part of the meeting was over. My discussion group of six people included Pete Wilson, a good-looking young man who also had a program on WBAI radio. Pete had a wonderful voice, and a remarkably sparkling, outgoing personality. I was drawn to him, and I remembered a lot of what he said, talking about how important it was for us to throw off old habits and fears. I certainly had enough of the old habits and fears, growing up in an extremely repressive atmosphere. I noticed, though, there was a distinct coolness to Pete. He was not someone to hug and smooch with other people. But he was very political and could talk an excellent political line.

"Several weeks after this first meeting, I went to Carnegie Hall for an afternoon concert. After it was over, while walking down from the balcony, I spotted Pete in the stairway. He approached me in the midst of a throng of people, and kissed me. He had never kissed me before at a meeting, or any place. I was embarrassed for a second; I was not used to kissing outside. We talked a bit, and I hid any concerns I had about being kissed in the stairway of Carnegie Hall. At the next GLF meeting, on seeing him, I walked up to Pete and kissed him.

"'Why did you do that?' he asked.

"I shrugged. It seemed the right thing to do. 'You kissed me at Carnegie Hall,' I said.

"'Oh, that was a political kiss,' he explained. 'You don't have to do that here.'"

Some topics weren't discussed, such as gays in the military or marriage, but we still had members who went off by themselves and dealt with those issues without the endorsement of the organization. Working with elected officials became a major effort of Marty Robinson and Jim Owles. Gay Liberation Front's support for the Black Panthers, and our numerous demonstrations outside the Women's House of Detention which then was in our neighborhood on Greenwich off Christopher, caused a rift. We'd often join the demonstrations and march and shout, "Hey hey, ho ho, the house of D has to go!" And our contingent would then shout, "Ho ho, hey hey, gay is just as good as straight!" Ultimately, these types of issues caused Jim and Marty and a few others to break away from Gay Liberation Front and create Gay Activist Alliance. The last straw for them was the support given to the Black Panthers.

Many of us felt religion was a fundamental element in our repression. When Reverend Troy Perry held a meeting in New York at the Summit Hotel on Lexington Avenue to organize a branch of his fledgling LGBT church, Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), we picketed. Yes, one gay organization picketing another. After his meeting, however, Troy came out to speak to us. He took me aside and explained that while we were effective at reaching some members of the community, we had little possibility of reaching those who were religious. His church gave people a place to go where they could be both religious and a member of the LGBT community. His point was pragmatic and started a friendship between us that lasts to this day.

The same holds true for my sisters and brothers in Gay Liberation Front. Being one of the youngest in the group, I was allowed certain liberties, and for that reason I was and am on good terms with most of our surviving members. They were my teachers, and all that I have accomplished has its roots in what I learned in GLF.

After GLF's incredible first year, many thought we should celebrate Stonewall and our achievements. Chief among them was Craig Rodwell, so he organized what is now commonly known as a gay pride parade. As I've already mentioned, its name then was Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day. I was one of the many who volunteered to be a marshal those first few years. One of the original posters from the event hangs in a place of honor in my den.

It was Sunday, June 28, 1970. No one knew what would happen since we intended to march up to Central Park without a permit. We held self-defense/martial arts classes at Alternate U where we learned how to protect ourselves, since we had no idea who or what would greet us. After all, we were going to march through the middle of Manhattan from the Village to Central Park. That march was one of the great products of Stonewall.

GLF changed the world in one year. Think that's an over-statement? Here are the facts: before Stonewall, the movement for LGBT equality consisted of one large national public demonstration each year on July 4 in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and of course the Compton's and Dewey's events and a couple of small regional pickets, such as the NY Army Induction Center picket by Randy Wicker in early 1965 which literally is the nations first first OUT gay picket. But the picket line at Independence Hall lasted from 1965 till 1969. No more than fifty to one hundred people attended. That was the preeminent LGBT demonstration of its day, and the picketers came from across the nation, though mostly from the East Coast. In a few major cities there were organizations like One Inc. (Los Angeles), Mattachine (Washington and New York), Daughters of Bilitis and Janus Society (Philadelphia), and a handful of others. That was it. In total maybe a couple hundred OUT people in the nation,

But Gay Liberation Front, along with its brother and sister organizations, wanted to create something more than just a march for equality.

Before Stonewall, these few brave organizations, and the people on those picket lines outside Independence Hall each July 4, all that existed were bars, secret gay hook-up venues, and private parties.

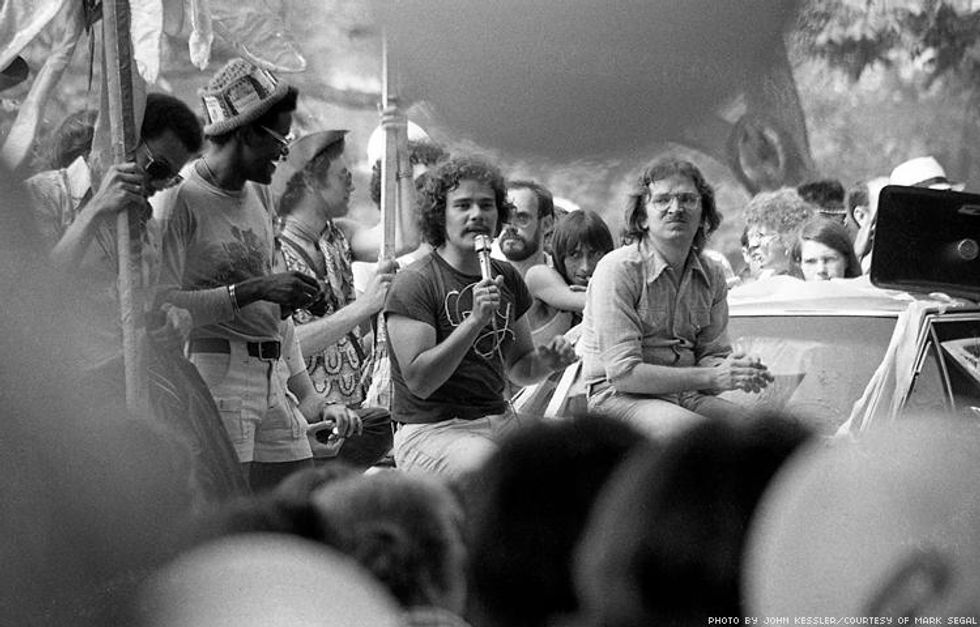

That Sunday morning we gathered on Christopher Street. By the time we reached 23rd Street, the crowd still reached all the way back to Christopher Street. Estimates were everywhere from 5,000 to 15,000 people. We had taken the movement from a brave crew of a couple hundred people willing to march in public at those Independence Hall pickets to what was now a march of thousands. That first year of Gay Liberation Front was one of the most pivotal years in the struggle for LGBT equality. As my friend Jerry Hoose used to say about that year, "We went from the shadows to sunlight."

And in 1972, when the gay pride march was officially launched, the New York Times reported on June 26, "The message of the march, according to Mark Segal, the grand marshal, was simply, 'We're proud to be gay.'" Well, I wasn't the grand marshal, and I wouldn't return to that march again until Stonewall 25--and then again in 2004, when Frank Kameny, Jim Kepner, Jack Nichols, some of my brothers and sisters from Gay Liberation Front, and I, among others, were put on two giant floats and recognized as pioneers of the struggle for LGBT equality.

New York City was for me the center of everything, especially the East Village, where I lived. At that time, it was not the trendy neighborhood it is today; rather, it was one of the most dangerous in the city and therefore affordable to me. Many of my new friends were connected to the outer fringes of show business: James, a dancer from Ohio, and his sister Kelly, who was dating one of the doormen at Stonewall. Mark "10 1/2" Stevens, who found a career in straight porn films even though he was gay and, as my parents might say, a nice Jewish boy. And then there was my roommate, Rosemary Gimple, and her friend Jeff Hochhauser.

Rosemary and Jeff had written a musical called Graduation that was being performed at New York Theater Ensemble. They enlisted me as their stage manager despite knowing that my only previous theatrical experience was in high school where I had one line in our school version of The Man Who Came to Dinner. (I was to appear at a pivotal point in the plot and shout, "Stop, I'm the FBI and this is a raid!" When I walked onstage my friends in the audience applauded and I froze.)

Graduation was the story of a teenage boy coming of age and accepting himself. It was, I believe, the first gay-themed musical on the New York stage and it led to my second and last job in the theater, managing a show down the street for Andy Warhol "superstar" Jackie Curtis. All I can remember is a song titled "White Shoulders" and what we would today call a transgender actress, Holly Woodlawn, whom everyone adored. Nearby was La Mama, which seemed to always have a show featuring a drag queen. Sometimes that drag queen was Harvey Fierstein, who went on to win many Tonys on Broadway and be inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.

The off-off-Broadway community was flourishing. On nights when you weren't working, you could get yourself invited to see these other offerings. One night for me it was a reading of an unfinished show titled Small Craft Warnings, which I knew nothing about. As I watched the first act, I grew increasingly agitated and annoyed. The self-pity of the gay character was precisely what my activism was trying to end. At that point, gays in the media had only three variations: pitiful, villainous, or suicidal, and this was going down that same old path. So with my newfound activism and left-leaning language, I stood up and shouted, "Bullshit! This is oppressive to gay men!" As I continued to go on about gay liberation, a small man made his way down the aisle to my row. He told me he was the playwright and that I should get the hell out of the theater. He was Tennessee Williams, who claimed fame following his blockbusters The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire. The show, when it officially opened, received poor reviews and closed quickly.

On another night Jackie Curtis invited me to a party at Andy Warhol's Factory right off of Union Square. The Factory was the hip hangout for socialites, drag queens, bohemians, intellectuals, and Hollywood types. I remember walking upstairs and winding up in a large, dimly lit loft with lots of people and not much food or drink. By the time we got there Jackie was already stoned. My fifteen minutes with Warhol were spent watching him walk aimlessly around the loft holding a jar of Hellmann's mayonnaise. Warhol, who lived as an openly gay man even before the gay rights movement, said a few unmemorable, indecipherable words and was off. Later on at the party, someone speculated about what he used the mayonnaise for; I'll spare you the details. There were many solitary people who ambled around without agenda, as well as groups of people who huddled tightly together like pickles.

The off-Broadway theater crowd hung out at Phebe's, which served the best burgers in the city. One night I met a guy who claimed to be a Broadway producer. Why would a Broadway producer be slumming on East 4th Street with the off-off-Broadway crowd? He invited me to stand with him in the wings and see his latest show in previews. The show was called The Love Suicide at Schofield Barracks and it closed after five performances. My friend Rosemary told me that the guy then tried the movie business. His name was Robert Weinstein. He made the right move.

Another friend, Charlie Briggs, was the assistant stage manager for the Broadway musical production of Purlie, starring Cleavon Little, Melba Moore, and a former Philadelphian named Sherman Helmsley whose TV audiences would get to know him as George Jefferson on the TV sitcom The Jeffersons. Little and Moore, who went on to have a major music career, won Tony Awards for their performances in Purlie. On my visits to the show, Helmsley and I would often compare notes on our home city. There has been much speculation about his sexuality since his death in 2012. While he certainly took a keen interest in our talks and my gay activism, there is nothing more that I can add to that discussion.

On another occasion Rosemary wanted to go to the theater to see a revival of an old musical, No, No, Nanette. She got us orchestra tickets in the next-to-last row for the final preview before its opening night at the 46th Street Theater. While I was reading the playbill before the show, Rosemary tapped me on my shoulder. She pointed across the aisle at two of our fellow theatergoers, Senator Ted Kennedy and his wife.

Rosemary, always a little amused at my dealings in activism, said with a smirk, "Why don't you ask him about gay rights?"

I smiled, got up from my seat, and made my way to Senator Kennedy. He was sitting up front in an aisle seat. I tapped him on the back, which startled him. A life lesson: never sneak up on a man who has seen two of his brothers assassinated. He turned in surprise and I introduced myself, after which I asked him his position on gay rights. He looked a little bewildered-- after all, the gay movement was still relatively new at this point. I watched each word as it tiptoed off his tongue.

"What?" he said.

I asked again, this time using the h-word instead of gay, and he replied, "I've never been asked that before, but I'm for all civil rights." I thanked him and made my way back up the aisle to my seat.

Along with No, No, Nanette, I got to see the original productions of Company and Follies, which resulted in a passion for the words and music of Stephen Sondheim, one of the only sophisticated elements of my quite makeshift life.

A few days later Rosemary's friend Keely Stahl somehow arranged tickets and backstage passes for us to attend a Beach Boys concert in Central Park. Rosemary suggested that I ask them to do a gay rights fundraising concert, but I only got blank stares from them when I explained what I wanted. Keely said they were too stoned to understand me. We left in utter amusement and wonderment of how they performed in such a state.

There was also a new and unusual kind of performance space called the Continental Baths in the basement of the Ansonia Hotel on the Upper West Side, which was actually a men's bathhouse. I had heard about this crazy lady called Bette Midler who sang up a storm there, so I decided to check it out. The bathhouse was a place for gay men to meet discreetly, but this was the early seventies and gay life was starting to bloom and smash out of the closets and businesses wanted to cater to this crowd, so they added entertainment to the mix of faux exercise, swimming pool, and anonymous sex. When I first saw the divine Miss M., she was singing by the pool accompanied by her pia- nist, Barry Manilow. Bette did indeed sing her heart out and she drew a much larger crowd than the space could hold. Crammed to the gills, people actually fell into the pool trying to watch her perform.

Bette glorified the camp humor in the gay community. In the middle of her performance she'd look down a hallway and call out, "Hey, boys, there's a girl out here working," or, "Come out, come out, wherever you are . . . I know you're in those damn rooms doing who knows what." She was so good that I had to have a recording of her performance, and I did the unspeakable: I took a tape recorder to the baths.

Not everyone walked around in towels, although most did, and it has been reported that even Manilow sometimes did so, though I don't believe that was the case. But Bette certainly brought in people who were there only to see her and who were not necessarily gay at all. Ah well.

After the success of the first two gay pride marches, it was decided that we needed something more than just speeches. We needed a feel-good moment as reprieve from all our internal fights; a moment to identify ourselves beyond turmoil. So Bette Midler's friend Vito Russo approached her and she agreed to sing at our third gay pride event. Susan Silverman, an early Gay Liberation Front member, recently reminded me that someone suggested that Gay Youth be in charge of Bette's security--and I got to be her bodyguard. What the hell did we know about security for a woman who at the time was becoming a national show-biz wonder? I vividly recall how she greeted us on the stairway to the stage that day. She looked up at me, since she was so short, and said: "Yeah, this is my security." She laughed, walked up the steps, and added, "Okay, boys, let's get this show on the road."

I was still young and poor, with no prospects but hope for the future, and New York was a wonderland; it allowed me to grow. From an emotionally battered kid I morphed quickly into a person with his own identity. The excitement never ended, and there was something new happening almost every day. While worrying about the police or FBI listening in on our phone conversations or planting someone in our meetings (we learned later that J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI actually did this), my group of friends expanded to include porn stars, drag queens, actors, playwrights, musicians, and even the prince of a small country. Then there were the eclectic spiritual beings of various varieties. I helped a friend open a short-lived witchcraft store at 119 Christopher Street. I wanted to explore every aspect of what I didn't have growing up. And thanks to Grandmom I was open to diversity.

My favorite book and movie growing up, as I've said, was Auntie Mame. It always reminded me of my grandmother Fannie. Somehow I discovered that Auntie Mame was based on a real-life woman named Marion Tanner who lived in New York. It became my mission to find her, and I did. She lived on the West Side and was running a boarding house. When I rang her bell, she invited me in and we sat at her kitchen table. She wasn't at all glamorous. She looked like she had been cleaning the house, which was exactly what I'd interrupted. When I asked her about the book, she delivered a cryptic line: "The book is like a plane: sometimes it's on the ground and other times it's in midair." She gave no details and wouldn't talk about her nephew Patrick Dennis, who wrote the book. I left that house realizing that I already knew Auntie Mame and she wasn't the lady I had just met. Her name was Fannie Weinstein and she was my grandmother.

Most evenings had me picking up my friend Doug Carver at his place at 11th Street between avenues A and B and walking over to Christopher Street in the West Village to attend meetings, hand out flyers, or just hang out at the Silver Dollar near the pier. We'd walk up and down that street all night meeting our friends and popping into bar after bar like the reopened Stonewall or the 9th Circle to see who was there. The scene was now very sociable, like when Grandmom would take me chair to chair on the Atlantic City boardwalk each summer.

Yet activism was not glamorous. Revolutions are work-intensive and that kept me living on a can of SpaghettiOs and potato salad for dinner most nights. We only bought clothes, usually at thrift stores, when the ones we had were worn thin.

To support myself--barely, since we were creating a revolution and had little time to make money--I had a litany of jobs. The one that kept me going was, like my father, driving a cab. Dover was my garage, and even today I have my hack license hanging on my office wall. My other part-time job was as a waiter at John Britt's Hippodrome, literally a rundown gay dive bar on Avenue A between 10th and 11th Streets. My most vivid memories of working there were from Monday nights when I got to be a bartender, since few people came in and John had no one else who would work just for tips. Only one customer stands out in my memory. Almost every Monday he'd sit at my bar, and often he was the only customer. We'd talk, but not about his business, which I'd learned many weeks into our relationship was dance and ballet. Robert Joffrey, of Joffrey Ballet fame.

As an organizer in the LGBT community, I was willing to drop any and everything just to be involved. This meant that I didn't always show up for my shift at Dover to get my cab. New drivers like me sometimes demanded the better cabs that often went to the longtime drivers, and that didn't sit well with the veterans. This led to a confrontation with three older drivers, all well built and intimidating, who cornered me one day and suggested that the garage didn't need f****ts making demands.

Since I couldn't live on the money from the Hippodrome alone, some GLF friends suggested a solution: sign up for welfare. For a guy from a working-class family who had escaped the projects and envisioned never being a part of that world again, this seemed out of the question. But when the rent was due and the landlord threatened eviction, I realized my friends had a convincing case.

According to them, the state was giving us welfare as restitution for the despicable treatment gays suffered. Since it was society that was oppressing us as citizens, why shouldn't we use their tools to fight back? When I researched how to sign up, it surprised me to learn that all one had to do in 1970 was walk in a welfare office and tell them you were "homosexual" and, because of that, you could not keep a job and therefore needed public assistance.

In desperate straits I made the journey and filled out the paperwork. As I waited for my turn to meet with the social worker, I wondered how hard the qualifying questioning would be and expected to be tossed out on my butt. When I finally got my turn, a bland man in a brown suit looked over my paperwork and muttered, "Homosexual." He stamped the paper and said, "You'll have to do counseling," and directed me to another window to finalize my acceptance. That was it, with no further questions. As I got out of my seat, my anger rose. What it all meant was that the state of New York classified homosexuality as a mental illness and we, as a group, were incapable of working.

Was I using the system or was I validating their belief system? Regardless, it angered me. We were both wrong--and this act was somehow further impetus for me to help bring about change.

Back on Christopher Street, welfare somehow gave me cred with my fellow Gay Liberation Front members, which made it a little easier to swallow.

My life now had a purpose: in a very short span of time I had gone from quiet high school student to gay revolutionary with a minor in theater on the side. It seemed there was a demonstration almost every week. Leafleting was constant as we grew GLF. There was no Internet, no cell phones--just feet. We handed out papers on the street as people made their way to a club or restaurant or we pasted them onto poles and buildings along Christopher, Greenwich, Seventh Avenue, and other areas of the Village.

Meanwhile, my parents still thought I was in school. And I was--at a place called GLF University.

***

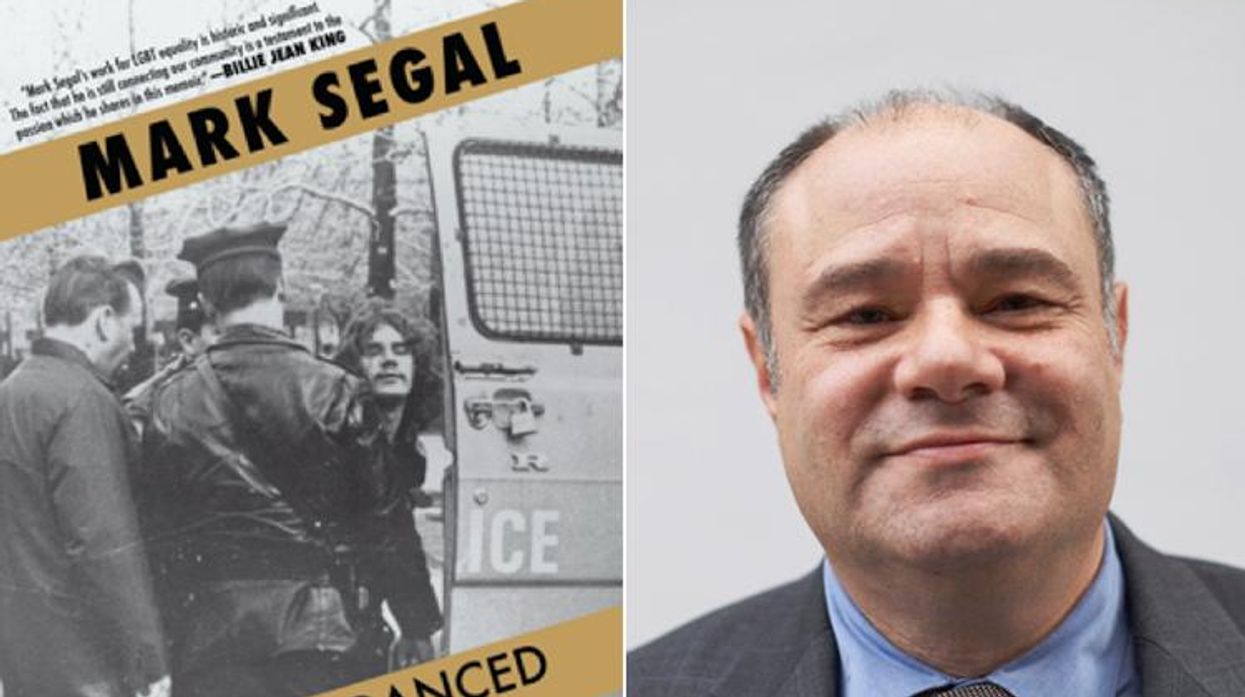

Excerpted from And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality by Mark Segal. Akashic Books, 2015.

MARK SEGAL has established a reputation as the dean of American gay journalism over the past five decades. He is one of the founders and former president of both the National Gay Press Association and the National Gay Newspaper Guild. Segal was recently inducted into the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association's Hall of Fame and was appointed a member of the Comcast/NBCUniversal Joint Diversity Board, where he advises the entertainment giant on LGBT issues. He is also president of the dmhFund, though which he builds affordable LGBT-friendly housing for seniors. He lives in Philadelphia.