In 1993, Philadelphia magazine named me the resident with "Most Clout" in their annual Best of Philly issue, crowning me above union leaders, corporate heads, and elected officials. By this time I had been in the public eye for nearly twenty-five years. It wasn't a quick rise, and the clout they attributed to me was garnered out of necessity. Any social justice or civil rights movement needs not only to understand the politics swirling around, but also to have insider clout. Change does not happen without working the system.

One can develop clout from a number of factors, like building coalitions with other communities, organizations, and leaders. Other important facets are the ability to raise funds and deliver votes, and being able to stop a candidate dead in their tracks. And the simple fact is that to get a large program on the boards or to get any sort of legislation passed, you need to be in tune with elected officials, both those who support your issues and those who don't. Knowing how to navigate the latter may indeed be even more important. One last item is getting the attention of media. Today, that means having an understanding of the power of both traditional and social media.

What to do with that clout, change laws and build a community by getting an equal share of our tax dollars.

My first foray into congressional funds, also known as earmarks, came in 1993. The LGBT Community Center at that time did not have a permanent location. Their slogan was "A Community Center without Walls." Fundraising was volatile, the board of directors mostly transitory, and the vision simply lacking. Tony Green, chief of staff to my old city council friend Congressman Thomas Foglietta, met with me for lunch to see what he and the congressman could do for our community. Formerly married to a woman, Tony was now openly gay. I told him about the center's predicament and he was receptive to earmarking funds. With funding, we'd be able to get a permanent location. He sent me the paperwork and we began the process. Along the way, he mentioned that "LGBT" could not appear anywhere in the paperwork, since that would alert the Republicans, who would vote it down. Our solution was to describe the building as "a place for the community most impacted by AIDS." That $300,000 earmark, the largest funding the organization has ever received, made it possible for what is now the William Way LGBT Community Center to purchase its building at 1315 Spruce Street.

Thanks to my early work with media and our efforts to pass a city nondiscrimination bill, I knew most of the city officials well. We asked for their support and also got valuable contact information to build my Rolodex. At my urging, Governor Shapp created the Governor's Council for Sexual Minorities, which further cemented my relationships with state leaders. Invitations to my house parties became coveted, especially by city officials and those hoping to break into politics. Where else could you see a Jewish governor singing Christmas carols with the Gay Men's Chorus? Along with regional bank presidents, union heads, a Socialist, and a drag queen all mingling with one another.

In the midst of all of this, District Attorney Ed Rendell, who was thinking about running for mayor, suggested that I form a political action committee (PAC). Almost as quickly as the ink was drying on our PAC filing, there was a fight in the city council regarding a gay pride resolution. It was a perfect reason to launch the Pride of Philadelphia Election Committee. Within weeks a cocktail party was held with leaders of the community, and Ed gave a speech about the importance of raising money in a campaign and the clout that the community could gain. There was also a hint that Ed might run for office again and could use a supportive PAC behind him.

That first fundraiser was memorable, to say the least. Pride of Philadelphia Election Committee at that time saw itself as a local version of the national Human Rights Campaign, and set as its first goal to gain passage of the pride resolution the following June in the city council. But in order to do that, we needed funds. Enter Barney Frank.

Barney Frank was the new gay hero to many of us, an openly gay man in Congress representing both his district and the greater LGBT community. Using the gifts of wit, intelligence, knowledge of history, and his famous Massachusetts drawl, Barney commands attention when he speaks. In 1989, when I first met him, you could say "Barney Frank" was synonymous with "pride." A PAC board member who was involved with one of Philadelphia's namesake organizations, the Franklin Institute, arranged for us to use space in the institute for our kickoff fundraiser. The plan called for cocktails in the observatory, then down to the planetarium for speeches and a private show. We had the venue, but we still needed a headliner. Congressman Tom Foglietta wrote a letter to Barney in July of 1989 asking him if he'd assist an old friend in starting a local gay and lesbian PAC. Tom's letter was accompanied by another letter from me telling Barney about my work.

Barney soon called and told me that he had followed my escapades over the years and would be glad to help. I then called Congressman Bill Gray and Mayor Goode to ask them to serve as honorary hosts. Both accepted.

Then, with less than two weeks to go, Barney was figuratively caught with his pants down. The scandal involved a callboy who was living with him and the ru- mors that the guy was running a service out of Barney's house. Barney told the nation that he knew about his roommate's background, but was trying to help him change his life.

As with all Washington scandals, it dragged on and on, and the roommate even started to do talk shows and tell about his sexual antics with Barney, true or not. As the scandal broke I tried to talk with Barney about the September 15 fundraiser. He did not respond personally, but several staff members kept telling me that they didn't know his plans.

Finally, I wrote to him and explained that the test of a friend's loyalty is when you are down, and in this instance we still wanted him since he was a hero, and heroes are heroes, even after falling from their pedestals. A week before the event, I returned home from a meeting to discover a message on my answering machine: "Ah, hello, Mark, this is Barney Frank, sorry that I've kept you in the dark this long. It's not fair and I'm sorry. I promised you I'd be at your function, and I'll keep that promise. Call my office tomorrow to make the arrangements."

This, it turned out, was the easy part. His staff was concerned about media. The press was now camped outside both his office and home. They followed him everywhere, and he was not commenting to them on the scandal. It was a typical DC feeding frenzy. Someone suggested that our gala premier of a new PAC should be staged without press. Then Barney's staff told us it would be a mandatory condition for his participation. I had to find a way to get this man, embroiled in the nation's number one sex scandal, into the city to attend a cocktail party, give a speech in a public place, and leave, all without the media catching on.

I faced the situation like it was a Gay Raiders zap. We stopped the sale of tickets. Only friends of board members could buy tickets. Security was set up at every entrance of the Franklin Institute. Drivers were informed that no reporters were to come near Barney no matter what. And no press releases were allowed. Meanwhile, a strange thing occurred: since most politicians run for the hills, away from their scandal-ridden colleagues, I was surprised to find that both Congressman Tom Foglietta and Ed Rendell called to offer support, and while neither had planned to attend, they both now felt compelled to in order to support Barney and the cause.

September 15, 1989 was a damp, drizzly, and windswept day. It matched my spirits. Members of my board were telling me that Barney would cancel at the last minute. After all, he had not made a public appearance since the scandal began other than a few attempts at talking with the press. It was decided that I'd be the one to pick him up and welcome him to the city. With my friend Bill Davol, who I thought would have a calming effect on Barney, we set off in the rainy night.

Barney arrived at the train station alone with one bag. I introduced myself and we shook hands, then made a quick exit before he was noticed. Bill was close by in the car. En route to the institute, I expressed my gratitude to Barney for coming, considering the toll that other matters might be taking on him at this juncture. He was mostly quiet, keeping his head bowed. Finally, worried about his state of mind, I said, "I recently wrote you about heroes and the way they sometimes slip. To me a hero is someone who fights for a cause no matter what might fall around them. The heroism is the cause, not their private life. To me you are still a hero." Barney lowered his head some more and began crying. We said little else for the rest of the ride, but I was worried. At the reception, the first thing I discovered was that we had succeeded in keeping the mainstream press unaware of the event. Since we sent out no press releases or advisories, the only way for reporters to know was to read the gay press. Imagine the firestorm that would have greeted us if they read the gay press regularly. For the first time in my life, I was thrilled that they didn't.

At the venue, some members of the board took Barney around the local politicians arrived to assist and lend support. It became apparent almost immediately that Barney was mentally not with us. We quickly arranged for a friend in attendance, a psychologist, to usher Barney from person to person, but he told us that he wanted to mingle on his own. Then he sort of ambled around the room, just nodding his head in acknowledgment whenever someone tried to talk with him. At one point he came up to me as I was going over the rest of the schedule with the board, and asked in a low voice, "Where's the bathroom?" I suggested that we'd have someone show him, but he declined and asked us to point the way.

We watched as he slowly made his way to the bathroom. Once the door had closed behind him, we looked at each other in total fear. We honestly believed that he was going to do some harm to himself. As we waited, I found myself thinking of how I would respond to reporters' questions about the dead congressman in the bathroom. Eventually, we all agreed to send someone inside. I asked Jeff Moran and his partner Richard Bond if they would make sure the congressman was okay. As they reluctantly approached, the door opened and Barney came sailing out. My sigh of relief could be heard all the way in Washington.

Congressman Tom Foglietta showed up, and we moved to the planetarium where the program was to begin. After everyone was seated I took to the podium and thanked the attendees for their support. The first speaker was Ed Rendell, followed by Tom who would introduce his colleague Barney. Tom spoke stronger and more eloquently then I'd ever heard him before. He reaffirmed his support of Barney and said he looked forward to working on a progressive agenda with him for many years to come. He then concluded, "Friends, let me introduce a fine gentlemen and a great congressman, my good friend Barney Frank!" The assembled rose to their feet en masse, and I could

see the tears in Barney's eyes. Like magic he woke up from what seemed like a walking sleep, and was full of energy. As he spoke he became stronger, and with each comical story he slowly became the Barney the nation had grown to love and appreciate.

After the speech, we had to get him to the airport to make his flight to Boston, and I hugged and thanked him, offering to help in any way I could. The next time I saw Barney was in the spring of 1994 when he and Congressman Gerry Studds came to my home for another fundraiser, this time for Tom Foglietta. My fondest memory, though, came many years later at a different event at my home. He and Congressman Bob Brady were both there, and Bob talked about how close he and Barney had gotten in Washington. Barney was so comfortable and upbeat that he slow danced with Bob, the same blue-collar guy from the tough neighborhood, the sergeant at arms who had the job of carrying me out of the city council thirty-five years earlier.

That first fundraiser at the Franklin Institute was merely an ap- petizer for the Pride of Philadelphia Election Committee. Over the next couple of years, the committee continually brought political surprises. One development in particular cemented the strength of the LGBT community; it was a perfect storm that I could exploit, and that storm was Fran Rafferty.

Rafferty was a city councilman with strong religious beliefs. He was a blue-collar Irish Catholic who had imaginative ideas about God and AIDS. He had a temper, which once resulted in a brawl with another councilman on the floor of the city council. When a gay rights issue came up in the council, he'd yell slurs like, "Fairies!" Beyond his antigay views, his other behaviors were, shall we say, not representative of the pride Philadelphians took in their city.

Most people thought of Rafferty as the most homophobic elected official in the city. It all came to a head when we introduced a resolution recognizing Gay Pride Month. He suggested that it be called AIDS Pride Month. This led to a series of mishaps and ended with a televised debate on a KYW-TV talk show hosted by Jerry Penacoli, who went on to Hollywood to report for the entertainment show Extra.

It was 1991 when we announced our campaign against Rafferty's reelection. The political elite of Philly thought the idea ridiculous. To be truthful, so did I. After all, he was endorsed by the Democratic City Committee and running in a city controlled by an entrenched Democratic machine. He had also been the top vote getter in the previous election.

The campaign organization was formed with two goals in mind. The first was to help Ed Rendell become mayor and the second was to defeat Fran Rafferty. Ed was almost a sure bet to win, but defeating Rafferty didn't seem realistic--until we realized that we could use Ed's campaign to work the ward leaders. We would need to find an acceptable candidate to replace Rafferty who the public could embrace and we needed to make the community and the city believe this was all possible. Television was what I knew, so we decided to produce a commercial. We had little money and a commercial campaign would wipe out most of our funds. This, we realized, would be a smoke-and-mirrors campaign. But it was worth a try. No pain, no gain.

Richard Bond, a public relations executive on our board, had a friend who sold airtime on the NBC station. Together, we began to research hot-button issues and put together a storyboard. In the end, the commercial would be a thirty-second spot. It was filmed secretly at NFL Films studios in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, at a deep discount. Yes, NFL Films must be thanked for helping produce the first-ever citywide LGBT political campaign television commercial in the nation. We sent Peter Lien out to photograph Rafferty with the instructions to get as many shots as possible with him looking mean. Mission accomplished. From my days at a radio station called Talk 900, we got Bill Davol to agree to do the voiceover. The spot was a collage of Rafferty photos; in each one he appeared progressively meaner. With the voiceover, we used his quotes and his votes to lay out the issues.

"You may have thought it was funny when Fran Rafferty insulted lesbians and gays. But was it funny when he had to apologize to Philadelphia for saying he would salute the Statue of Liberty by getting drunk? Or when he voted against more money for our children's education? Or when he made the city council a laughingstock by having not one but two fistfights there? The sad thing is, Fran Rafferty could be elected again to the city council. If you're serious about Philadelphia, don't waste $65,000 a year . . . Say no to Fran Rafferty."

I believe the commercial cost us under a thousand dollars to produce. We then tried to place it. There, we ran into a surprise: most of the stations were afraid to sell us time. No one had ever run an ad against a sitting city council candidate without being a candidate themselves.

We called a press conference and announced that only two TV stations would sell us time for the commercial. This was outrageous. We thanked the two stations, KYW and WPHL, and told the assembled press, which included the stations that wouldn't sell us time, that the commercial would begin running the following morning on the news shows. That night the six p.m. and eleven p.m. news on most stations led with the press conference, with the commercial as part of the story. We ended up getting the commercial on TV free of charge and it ran more times on the news than the airtime we'd actually purchased.

But the true magic of that moment was that we were the first LGBT group to ever fight a standing councilman with a TV campaign. We made bumper stickers with the Say No to Rafferty logo next to a snarling Rafferty. We handed them out and they began to appear all over the city. People like activist Mike Marsico and members of ACT UP kept coming back for more stickers for their army of friends and colleagues. People saw them and recalled the commercial, and it appeared as if we had a citywide campaign going.

This led to the most powerful member of the Pennsylvania Senate calling and asking to have lunch with me. Enter Vince Fumo, not only a state senator, but also a ward leader, who was trying to help get his friend Jim Kenney elected to the council. Vince felt that if our campaign took votes from Rafferty, it would help Kenney win. The idea was to take Rafferty off the list of endorsed five and replace him with Kenney, and to do it ward by ward. Finally we had found our candidate! Once agreed, Vince began to call ward leaders and I'd take them to lunch at The Palm.

We won!

The following morning, I was awakened by the phone ringing. It was Senator Fumo, who greeted me with an incredible laugh: "Congratulations!" He went on to say a lot more, but all I heard was that one word. When I finally roused and regained some ability to understand the situation, Vince made me realize the importance of what we had done, but also some of the finer points of the game of politics. "Mark, you won, but Fran has a family to feed. We have to give him something. How about if we put him on a commission?" This was a level of politics I had no knowledge of, and all I could say to the man who had first reached out to help was, "If that's what you feel is correct."

In hindsight, I realize Vince was explaining to me that we had just knocked off a giant, and in victory we should offer an olive branch. After all, the giant could rise again, if not placated. The fact that Vince even asked me was a sign that he respected the campaign we had launched, and understood that this made the LGBT vote a powerhouse. In the subsequent election, we continued to make a pro-gay difference in local politics, leading the president of the city council, John Street, who at that time was considered a homophobe, to spend $400,000 to protect his own seat.

As Ed began building his mayoral team, he appointed members of our board to his administration. Some elected officials suggested to me that Ed should offer me a position of deputy mayor. This went to my head, and I let it be known to media friends that out of respect, I should be asked. Word got around to Ed's campaign manager, David L. Cohen, who called and made the offer, but also told me that I wouldn't be happy, since taking that position meant that I was no longer independent. I'd be part of the administration and would have to voice their positions. David was right, and I quickly declined the offer.

The first week as mayor, Ed called me to his office. He was leaning back in his chair with his feet up on the desk.

"What commission or board do you want?"

"How about the airport board?"

Ed was surprised, and suggested several boards and commis-

sions that offered compensation, and I responded, "The airport board."

He looked at me sternly. "Why? It doesn't pay anything."

My answer: "Mr. Mayor, I want to be Philadelphia's first official flying fairy."

Ed still likes to tell that story.

James Carville, one of the nation's most renowned political consultants, showed me his tremendous charms during our first conversation. Jim is often credited for the Clinton White House victory, and the man knows how to win debates. He is a lover of the political deal and I got a taste of that early in his career. Robert Casey Sr., the father of future US Senator Bob Casey Jr., was running for Pennsylvania governor in 1978, and Carville was his manager, willing to do whatever it took so that this would not be Casey's fourth failure in getting to the governor's mansion. It was during this campaign that Carville uttered his famous description of Pennsylvania. He said in his Louisiana drawl, "On one side of the state you have Pittsburgh, on the other Philadelphia, and in the middle is Alabama." Some have since remarked that his description is an insult to Alabama.

The polls were running pretty even and Casey needed one more thing to go his way to pull off a victory. The old Democratic coalition was drawing together to support him, but the

gay community was suspicious of Casey and his devotion to the church. He had not met with gay leaders or made his position on gay rights known. What's more, my newspaper was not offered an opportunity to interview Casey and find out what he stood for and how he would apply that to the gay community.

It was in this atmosphere that I picked up my phone one day and was greeted by: "Mark, what the hell do I have to do to get you to support Bob? This is Jim Carville." Taken aback, I said hello and asked why he was the one calling. He explained that since Bill Bateoff, a campaign fundraiser and acquaintance of mine, had been unable to make a deal and get me on board, he thought he'd give me a talking-to.

I replied that it was very clear what was required for my support. Unlike others, there was no need of patronage, state funding of any particular organization, or bond issues to any law firms I was associated with. All I needed was for Casey to support the state's gay rights legislation when introduced in the legislature, and to recreate the Pennsylvania Council for Sexual Minorities that Governor Shapp had started and which had died under Shapp's successor.

"That's all?" Jim uttered.

I immediately said, "And one more item: an interview in my newspaper, so he can give his remarks on these issues."

"Done deal," Jim responded.

After the interview was published, Jim called to thank me for handling Bob in a polite and professional manner. At that point I asked what I should do when Bob doesn't keep his promises. After telling me that should not be a concern, since Bob always keeps his word, Jim said, "You have Bill [Bateoff] talk to Bob, and if he can't take care of it, you call me and I'll set him straight."

Governor Robert Casey broke every promise, and I'm still waiting for Mr. Carville's return call.

It was around this time that I got a call from an up-and- coming union leader by the name of John Dougherty from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. We set up a meeting and he asked what he could do to help the LGBT community. Never one to shy away from the big ask, I explained that we had just purchased a building to be used as our community center and it needed some electrical work. Being a generous guy, John replied, "Not a problem, consider it done." He sent over a few apprentices to take a look and unfortunately, the building needed a completely new electrical system, which would require more then a few apprentices. To his credit, John never told me what the price tag on that job would have been. Certainly a price tag the center could not have paid.

Later I'd discover that John was doing this in part as a way of showing his daughter his support of the LGBT community since she had recently come out to him. We've gone on to engage in many battles together, sometimes even opposed to one another, but we remain friends and enjoy a special bond.

Street, to his credit, quickly began to reach out to me. It might be relevant that he was about to run for mayor. I gave him an education on the subject of domestic partners and we soon became friends. I wouldn't be endorsing him for mayor, since he was still painted as a homophobe, but he and I knew that this didn't mean we couldn't start a dialogue.

In time Street began to question his own position on the matter, and this led to us having long discussions. As mayor, he actually did more for the gay community than Ed Rendell. He fought all the way to the state supreme court to protect Philly's domestic partners law, the one he originally fought against. And he won. He also launched a war on discrimination against gay people in the Boy Scouts and he both funded LGBT organizations and hired LGBT staffers.

The highlight for me was when he personally performed the domestic partners ceremony for his gay staffer Micah Mahjoubian and his partner Ryan Bunch. In a front row seat in an ornate City Hall room, I watched as Mayor John Street talked about marriage and how it should be afforded to all. This was the end result of legislation that he had opposed five years earlier and a testament to the power of education. To conclude the ceremony, Street brought out a broom. He told a story about slaves who were forbidden to marry without the permission of their owner. "They'd call the ceremony 'jumping the broom.' Since it is outlawed for LGBT to marry in our country, like it was for slaves, it is appropriate for you, Micah and Ryan, to jump the broom." When he laid it down before them, there was not a dry eye in the room.

My coalition had beaten him on domestic partnership legislation and now he had won the battle for city council supremacy. We both had a good laugh to accompany our lunch.

In 2011, the Philadelphia city council passed the most far reaching LGBT legislation in the nation. It was a well-needed update of an old piece of legislation. Sponsored by our friend and Rafferty replacement, Councilman Jim Kenney, the legislation now included trans issues; it even gave tax credits to corporations that offered trans benefits.

when I asked Jason, my partner, "Do you think I can raise nineteen or twenty million dollars to build an affordable LGBT senior living facility?" he looked me in the eye and said, "Of course." He might have believed so, but to me it was a pie-in-the-sky dream, and that's what the project became. Inspiration had begun in 1998, when we received a state grant to look at issues facing LGBT seniors.

We conducted a survey, the results of which surprised us all. The number-one issue facing LGBT seniors was housing. Not only the issue of affordability, which affected them like all communities, but the treatment of these seniors in existing low-income housing. Many people seemed to think that "gay" and "low income" could not be uttered in the same sentence. We were being stereotyped as typically childless, two-income households with lots of disposable funds. This was incorrect.

Significant credit was due to Mike O'Brien, my state representative who identified with the problem and was responsive to my interest in creating LGBT-friendly affordable housing for seniors. His advice was simple and something that nobody had told me in a long time: "Mark, you're not pushy enough." Mike, a proud, heavyset, blue-collar Irish Catholic member of our state legislature, sat me down along with his chief of staff, Mary Isaacson, to tell me the political facts of life as he saw them.

"Mark, you've supported the Democratic Party for forty years and you finally want something back. It may not be for yourself, but you want something and they owe it to you. It's about time you start demanding. Be pushy again."

Mike was correct, and that chat is what really put this project on the road to becoming a reality. Once again I was not knocking politely on doors--I was busting them down. But it started a little before those words of wisdom from Mike.

The funding gave us the ability to do what had become a pattern with each of my successful initiatives: find a partner who can look after the details. After all, I may have a strong vision but I sometimes lack skills in the small-details department.

From Mark Horn and my founding of Gay Youth in 1969, to Harry Langhorne with the Gay Raiders and the disruption of The CBS News with walter Cronkite, Jane Shull with AIDS Awareness Day, Andrew Park and Andy Chirls with the domestic partnership crusade, Dan Anders and Jeff Guaracino and the Elton John concert, the incredible staff at Philadelphia Gay News who allow their publisher the time for other endeavors, and Klayton Fennell at Comcast-NBCUniversal--I always surrounded myself with top-notch and highly skilled professionals. Each one was an equal partner, keeping me on track and sometimes in order. And they all had something in common: they were much smarter and much more diplomatic than I am, and they paid attention to details.

This would become the biggest project of my career--the $19.5 million facility would be the largest LGBT building project in the nation created entirely with government funds and tax credits.

A couple of years later I was in the governor's office asking for more state funds. So began an endless procession of meetings with public officials and department heads to find the right formula for the funding. "Equality" was now a key word, and we ran with it, arguing that we were pursuing this project in the same way that Catholic charities and Jewish federations do their senior homes. All we wanted was equality, to be able to build our project in the same way. The first group to understand this was the team at the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. With the assistance of HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan, and his able deputies Dr. Raphael Bostric and my longtime friend Estelle Richman, we became the first federally designated project with the acceptable designation "LGBT-friendly." That in turn allowed us to apply for funding.

Sometimes when you're so involved with numerous meetings to secure funding, gain community support, and round up corporations to partner with, you lose sight of why you're even doing the project.

There were my Gay Liberation Front brothers and sisters. Due to age and illness, some were left isolated, far from the community that they had helped create. There were also those who lived in religious-based low-income homes and were being mistreated by the staff and shunned by the other residents.

This is the first out generation. The way we treat the needs of our pioneers will define our community, just as the call to help our gay youth and trans communities did in the early days of the movement.

And we as a community were failing. Gay rights pioneer Frank Kameny, for many years and up to his death in 2011, had to constantly call friends to request money. In 1957, Kameny was the first US government employee to fight being fired because of his "homosexuality," thereby launching his activism. He lived long enough to get an apology from the president of the United States, Barack Obama.

Shame on us! Near his death, Frank still lived in his mother's home (he actually owned it), but to generate the funds to live and be an activist, it was mortgaged to the hilt. Frank's friends, including Bob Witeck, Charles Francis, Rick Rosendall, and Marvin Carter, took over his finances and attempted to put him on a budget, but somehow Frank, who for years begged, couldn't or wouldn't conform.

The year before Frank died, my friend Jeff Guaracino, who at that time was working to generate tourism in Philadelphia, asked me to help arrange the honoring of some of our early pioneers. So in a parade on July 4, 2010, Frank Kameny rode past Independence Hall in a convertible car with a banner in front stating, Early Gay Rights Pioneers. Forty-six years before to the day, he had been picketing at that same historic building. As always, Frank wore a suit and tie on that hot, humid July 4, but the suit was old and worn. Frank wasn't begging for funds any longer, but he couldn't get used to the changes that came late in life. At lunch after the parade, he asked if he was allowed to order anything on the menu.

No senior, much less a pioneer, should find him or herself at an advanced age with little resources from our community. For a long time, seniors were, literally and figuratively, the last issue to be considered.

Frank is a good example of our pioneers who live in poverty. We need systems and assurances in place similar to what we now have for gay youth.

So what does the future hold for our elder community? To answer this question, we should first ask: how much do we know about them? We know much about youth and bullying issues, much about our LGBT citizens in military uniforms, much about those couples who wish to marry and have children. Even those interested in playing professional sports. But what about the elders? We know very little, and that is a sign that our community's agenda has, for the most part, left them behind.

There were zero LGBT senior advocacy programs in our region when we began. We started by funding the Delaware Valley Legacy Fund, which resulted in the creation of the LGBT Elder Initiative spearheaded by a man named Heshie Zinman. We met with every mainstream senior service organization in the region and requested their help and lobbied for their inclusion of LGBT seniors. We asked for seats on governmental senior boards and commissions. And we helped fund another study on the concerns of LGBT seniors, this time by the Philadelphia Health Management Corporation, and once again found that housing was a major issue.

In order for us to receive the tax credits needed for the project we had to be approved by the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency, which was headed by Brian Hudson. We staged an all-out lobbying campaign to get those tax credits and he, poor guy, was on the receiving end. But instead of asking us to stop, he actually encouraged us, realizing that we might be needed later for public support. It must also be stated here that the staff at PHFA, a state agency then controlled by a Republican governor, gave us every bit of support requested. They treated us as equals. Which is all that we asked.

As expected, once we made it public, the project irked some in the gay community. The community center called a public meeting to discuss the proposal. While we were ultimately given a yellow light to proceed with caution, my takeaway from that meeting was the image of a young man standing up and screaming at the top of his lungs, "If you build this old person's home on top of the community center, no young people will ever come here again!" After forty long years of fighting, I couldn't resist yelling, "Ageist!" back at him.

That young man soon left the city to go to school out of state. But there were others in the community who felt the clientele for an LGBT-friendly low-income building would be, in their words, "drug addicts, drag queens, and prostitutes." My response was that people selling drugs would be in violation of their lease and tossed out. Who would be calling a sixty-two- year-old prostitute? As for the drag queens, bring them on, we want them!

We were simultaneously negotiating with the community center, designing the building with the architects, working with our co-developer Jacob Fisher of Pennrose to finalize the paperwork that would be submitted to the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA) for funding, and explaining to city and state officials that the federal government would accept the term "LGBT- friendly" and that it was not discriminatory in any way. We were trying to organize an advisory board from the community to ease any problems with the neighborhood associations, and all along keep our eyes out for any new objections that surfaced. We were in heavy negotiations over our contract with Pennrose regarding ownership, property management, and the responsibilities of each party. We also had to work out agreements with unions, since we wanted to have LGBT contractors involved with the construction. It was an incredible juggling act.

Our negotiations with the community center fell through along the way due to differing expectations related to repairs and operating expenses. We parted on good terms.

When we entered discussions with the city for a parcel of land on 13th Street, Mayor Michael Nutter pushed his administration along with record speed. It was a choice parcel, and some people really didn't want to give it up. The mayor deserves tremendous credit, along with the Redevelopment Authority's board chair James Cuorato, for making it happen. With the new location secure, Jacob Fisher pulled all the strings together and completed a new plan. From the time we parted ways with the community center, came up with that property on 13th Street, and drew up the new plans, a mere ninety days had passed--we were rushing to make the filing deadline with PHFA.

Meanwhile, Republican Tom Corbett was elected governor-- and we discovered that Ed Rendell hadn't been able to complete the state's part of the project. So I had to go begging a new Republican governor to finalize the state funding. Pennrose had a good relationship with the Corbett administration, but to ensure our success, I began to make myself known within the governor's circle. Soon I was told that if it was a good project, they'd fund it. They not only did this, but when various issues stymied us, as they usually do on a project of this magnitude, the administration was always fair and helpful. They helped calm the waters. Then, in April of 2012, we were approved for tax credits. This is how I wrote about it that week:

"On Monday we announced that the pie-in-the-sky project, which was made public about two years ago, is now a reality. For many of us, it's the most ambitious project we've ever undertaken. To find a home, a safe place to give our LGBT seniors to live; to bring them a home to thrive in their very own community--that's the goal. I have no illusions that the proposal has many more milestones to meet. It is not a done deal yet. And it will take the support and input of the entire community and our elected officials who have committed to follow through on this dream.

Last Thursday, the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency met to decide which projects would be awarded tax credits this year. I'm happy to report that the pie-in-the-sky project was awarded credit in that very competitive field.

The project is now fully funded at $19 million. It is, as the mayor said during the announcement, the largest LGBT-friendly capital building project in the United States. The White House and HUD spotlighted the project as "pioneering innovation in US housing solutions for low-income LGBT seniors."

Good things kept coming our way. When our board decided to name the building after John C. Anderson, a former city council

member who was both African American and gay, and who had died from AIDS, we had no idea of the impact it would have. At the groundbreaking for the building, State Senator Tony Williams spoke with great emotion: "You may have bridged the gap between the African American and LGBT community with this building, since it is to my knowledge the first building in America purposefully named after an LGBT African American public official."

When Mayor Nutter broke ground on the project, he was joined by former governor Ed Rendell, US Senator Bob Casey, the entire Philadelphia congressional delegation led by my old friend Bob Brady, Brian Hudson, who was president of the National Council of State Housing Agencies, various other state representatives and senators, and members of the city council--headed by Council President Darrell Clarke--along with District Councilman Mark Squilla. The council had suspended rules in order to pass our zoning changes, unanimously.

By the time we started to build, the vision had grown. We understood that we had to nurture a broader LGBT senior advocacy movement. We knew we couldn't do it alone and we wanted this project embraced by the community and dearly wanted them to have a feeling of ownership. So we went back to the community center and suggested that once we opened, they could take charge of the activities and social services. We asked the Mazzoni Center to create courses on law and safe sex. ActionAIDS was chosen as the HIV/AIDS services agency in the building. We even built an office on the first floor for outside organizations to work from.

Joe Salerno became our architect; he was a gay man who wound up, in a way, coming out during the process. My instructions to him were simple. We were building in an upscale area, and the concept must give our residents dignity. I wanted them to feel that "wow" factor when they walked through the front door. Joe and I came to a quick agreement, though Pennrose didn't like how much our vision would cost them. I had learned that a good partnership always involves compromise, so with every change they'd explain how much it would cost, and we'd attempt to find savings in another area.

The vision: Enter the building into a spacious open area with staff offices and resident mailboxes. Walk a little farther and you'll discover the lobby and library, complete with etched glass and fireplace. Sitting by the fireplace, you can peer out through glass windows that reveal a five-thousand-square-foot private courtyard with paths, benches, and even a fountain. There's a community room with an eighty-inch flat screen and seating for sixty. Farther down the hall is a computer lab station for the residents with five computers hooked up to the Internet. On the fifth floor there's a sundeck with sweeping views of the city's skyline.

Negotiating all of those areas, especially my request for glass walls, was a constant battle with Pennrose, with Jacob Fisher in the middle. But they were eventually completed and, in my opinion, completely worth the cost. The one item that most surprises people actually happened by mistake.

At our first meeting with the full construction team, many of whom were men employed by our general contractor, Domus, we all gathered around a table in one of Pennrose's conference rooms. Joe, who was reviewing the architectural drawings, noted that due to the shape of the building and the configuration of our courtyard, four apartments would have larger closets and a smaller bedroom than the others. I explained, "That's not a problem for our proposed clientele. We'll call them 'drag queen closets.' In fact, can we do the same in all the apartments?" The look on their faces was priceless as they all began to smile. Those closets are one of the most popular features of the building. Residents must be sixty-two and above and earn no less than $8,000 a year and no more than $33,000. Surprisingly or not, there are lots of LGBT people with low incomes, especially those seniors about whom we know so little. Consider, as just one example, a trans person in 1969. What kind of job could they keep, and what savings, Social Security, or pension do you think they would accrue thirty or forty years later? Think of those stereotyped and shunned individuals in the 1960s who

had to receive welfare in order to survive.

During the construction, we'd offer tours of the site to those who had taken part or those we wanted to get involved in the project. My friend Klayton Fennell from Comcast sent me a box of pink hard hats to give out on tours, and soon it became fashionable for a public figure to be photographed wearing one while touring the site. Those hard hats with our logo have become collectors' items.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development asked us to showcase the project at their first conference on LGBT senior housing. Webcast live from their headquarters in Washington, DC, they and the White House hailed the project. From that meeting with President Obama in 2012 to the day we took in our first resident, only three years and nine months had passed. Yes, that was record timing for a project like this. Since opening, we have been deluged with requests to both tour the building and assist those wishing to replicate our success.

At the ribbon cutting on February 24, 2014, I took the microphone to welcome the large crowd. I pulled out a letter I had recently received and began to read it:

"I send my warm regards on the opening of the John C. Anderson Apartments. For generations, courageous lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans spoke up, came out, and fought injustice, blazing trails for others and pushing us closer to our founding ideals of equality for all. In the face of impossible odds, these leaders and committed allies demonstrated that change is possible and helped our nation become not only more accepting, but also more loving. And across America today communities are tackling challenges that remain and writing bold new chapters in this story of progress.

By working together as advocates, business leaders, and officials throughout government, we can address the problems of LGBT discrimination in housing. Offering security and affordability for Philadelphia's LGBT seniors, this apartment community is an example of how we can create a more hopeful world when we better care for one another. My administration stands with all those in the fight to ensure every American has equal access to housing--no matter who they are or whom they love. May this effort inspire us to continue striving for equality for all people in our time.

As the John C. Anderson Apartments opens its doors, I hope it provides warmth and comfort to all who call it home. I wish you all the best for years ahead.

--Barack Obama"

Clout builds community.

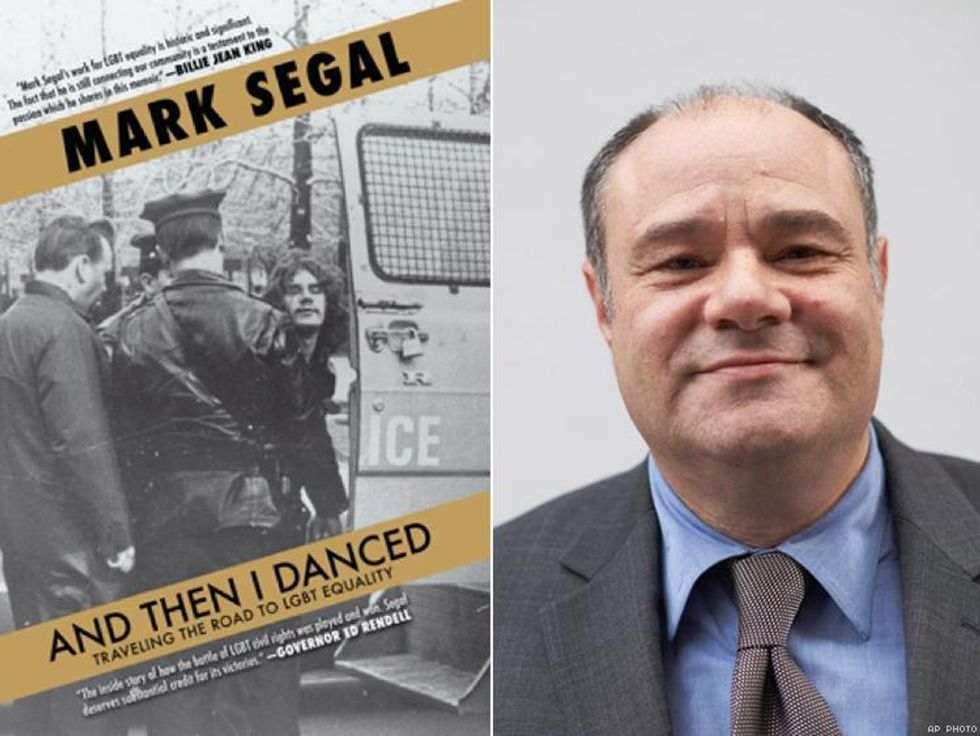

Excerpted from And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality by Mark Segal. Akashic Books, 2015.

MARK SEGAL has established a reputation as the dean of American gay journalism over the past five decades. He is one of the founders and former president of both the National Gay Press Association and the National Gay Newspaper Guild. Segal was recently inducted into the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association's Hall of Fame and was appointed a member of the Comcast/NBCUniversal Joint Diversity Board, where he advises the entertainment giant on LGBT issues. He is also president of the dmhFund, though which he builds affordable LGBT-friendly housing for seniors. He lives in Philadelphia.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes