The following is an excerpt from Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880-1945 by Clayton J. Whisnant:

As early as the turn of the century, Berlin's gay scene was attracting such notoriety that it frequently was mentioned in tourist literature, lifting up the city's gay scene as proof of the evils of urban life and the dangers of modernity; in them, Berlin became the country's Sodom and Gomorrah put together, a sure sign of the land's degeneracy.

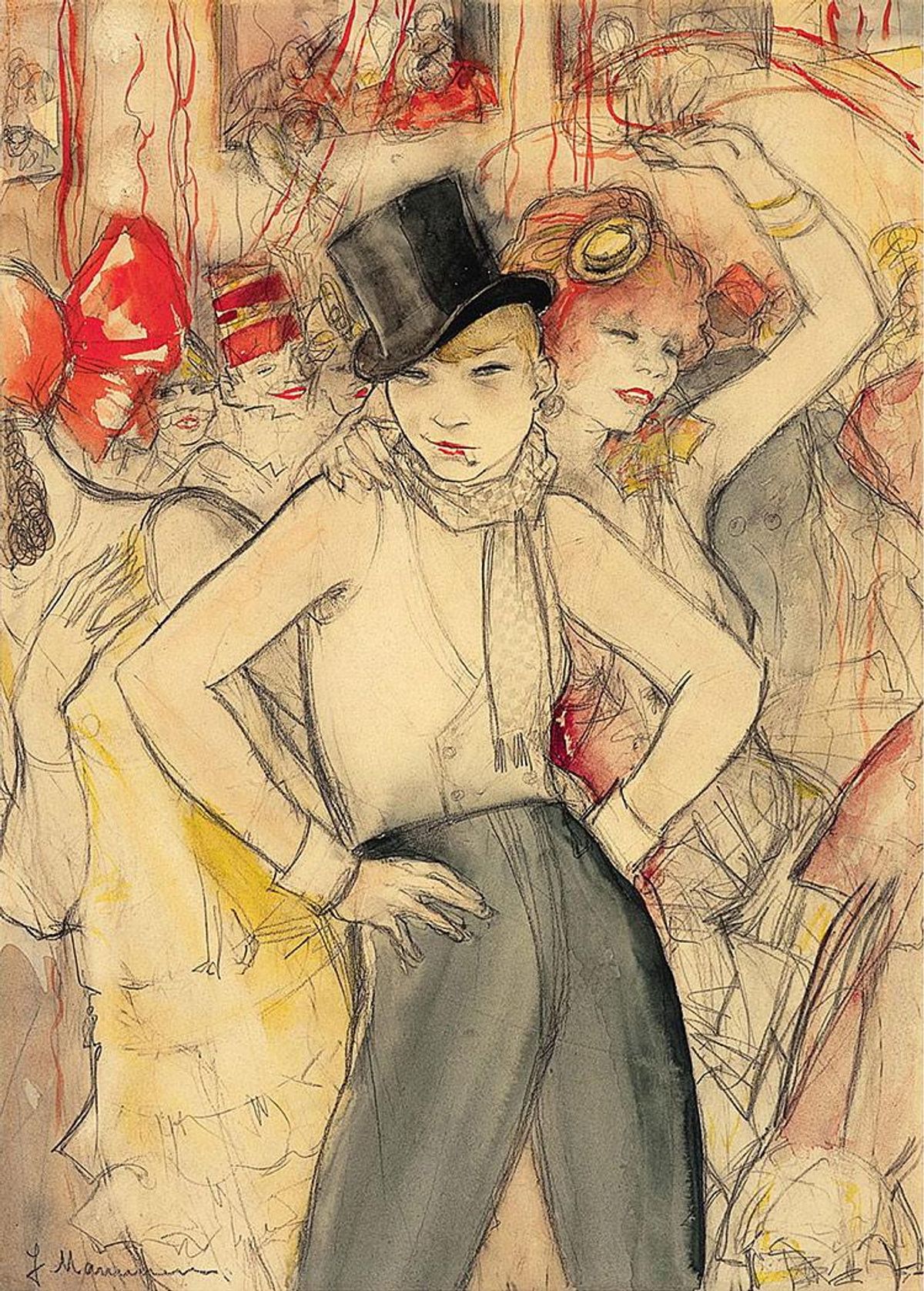

On the stages of Berlin, the Tiller Girls showed off their legs, dancing a Rockettes-style performance that amazed and titillated spectators. In crowded cabarets, audiences admired "tableaux" of women posing naked or watched actors telling risque jokes and singing lewd songs

Clubs full of men wearing powder and rouge as well as shorthaired women dressed in tuxedoes offered images of a world seemingly turned upside down. For the general public, this world was bewildering--and quite possibly terrifying.

For Germany's gay men and lesbians, though, Berlin represented promise. Its gay scenes offered exciting places to hunt for love and happiness. Christopher Isherwood, whose short stories based on his stay in Berlin eventually became the basis for the 1972 film Cabaret, with Liza Minnelli, put it simply enough: "Berlin meant boys."

Diverse, but Divided

Magnus Hirschfeld, a Jewish German physician, sexologist and pioneering gay rights advocate, was well acquainted with Berlin's scene and commented on the diversity among the bars. He observed that each bar "has its special mark of distinction; this one is frequented by older people, that one only by younger ones, and yet another one by older and younger people."

There were larger clubs that offered singing, cabaret, and theater, whereas smaller ones focused more on giving men a chance to mingle among themselves, perhaps providing a piano player to offer entertainment. The establishments were divided by the social background of their clientele.

"There are bars for every social level," Hirschfeld pointed out, "elegantly outfitted bars in which the cheapest drink is one mark, down to the middle class taverns, where a glass of beer costs 10 pennies."

Soldiers and Hustler Bars

At the bottom were the hangouts for working-class men, many of them male prostitutes. Some of these were frequented almost entirely by soldiers looking to make some easy cash.

One of these soldiers' bars, The Mother Cat (Zur Katzenmutter), was visited by the criminologist and psychiatrist Paul Nacke in 1904. Consisting of two small rooms on the ground floor of a larger building, one of which was decorated with small pictures of cats, the bar was packed the night that Nacke visited. "Almost half of the visitors were soldiers of different sorts, although they all sat apart from one another and often with a civilian instead."

He watched as the hostess brought beer to the patrons, who talked with one another and occasionally left together. Outside the bar was a street where soldiers hung about, waiting to leave with "anyone who would take [them]." Not surprisingly, most of these bars were in the vicinity of the soldiers' barracks. They very often were short-lived, since the military quickly moved to shut them down once the authorities learned about the activity going on there.

Besides the Mother Cat, Nacke visited several other bars that were gathering places for gay men from the working classes and lower middle class. They also tended to be small--again, normally with only two rooms--but the atmosphere might be slightly more festive.

Wigging Out

In one of the establishments, he had the pleasure of hearing the local bartender sing a song about "the third sex" that one of the members had composed. As the bartender sang, he threw off his apron, pulled on a braided wig and woman's hat, and "made all kinds of feminine movements and facial expressions that a professional female impersonator could hardly improve on."

Another of the bars was full of feminine-acting men, many of whom were dancing together in pairs in the main room. Everyone behaved well, and in fact Nacke commented on how clean and orderly the bars were. He saw no evidence of drunkenness; he saw nothing lewd and did not even hear a dirty joke. The most shocking thing he saw all night was a couple who were kissing quite passionately in one of the corners of the room--and even this he did not find particularly "disgusting."

Nice Boys Without Sweaters

Years later, Christopher Isherwood (whose short story about his years in Berlin was the basis for "Cabaret") would make a similar observation about the first Berlin bar that he visited with his friend W. H. Auden in 1928--a place he called the "Cosy Corner" in his autobiography, but which in fact was Noster's Cottage (Noster's Restaurant zur Hutte). First established in 1909, Noster's Cottage was a pub near the working-class district of Hallesches Tor, one that was normally avoided by tourists.

Despite the rough neighborhood, though, "nothing could have looked less decadent than the Cosy Corner. It was plain and homely and unpretentious." On the walls hung photographs of boxers and racing cyclists. In fact, the only real attraction was the boys. With their sweaters and jackets taken off, "their shirts unbuttoned to the navel, and their sleeves rolled up to the armpits," they waited around patiently for locals to come and pick them up.

On Saturdays and Sundays the bars were often packed beyond capacity. Music was common: "Piano player and singers, who are often called by feminine names, are generally popular and, like the waiters, who are often the partners of the owners, are smothered with compliments and friendly words by the guests."

In many of the restaurants, effeminate homosexuals felt relaxed enough to "give free rein to their feminine nature." And men felt comfortable enough to dance close to one another, as one partner "languish[ed] in the arms of his leading partner."

Come to the Cabaret

The chief Berlin attractions were the transvestite venues. By far the most famous was the Eldorado a nightclub whose festive atmosphere attracted not only homosexuals but also artists, authors, celebrities, and tourists wanting to admire a piece of "decadent" Berlin or catch a glimpse of someone famous.

The Lesbian Club Scene

Lesbians could also be found in some of the bars that were devoted mostly to gay men [and were] often seen in the larger clubs of the 1920s, such as the Topp and the Eldorado. The Dorian Gray, one of the oldest and best-known gay clubs by the Weimar era, had a special night set aside for women.

By the turn of the century, there were also a handful of exclusively lesbian bars in the city. After the First World War, the number of lesbian clubs and cafes exploded, and by the mid-1920s there were over fifty of them in the city, which were as diverse as the male establishments in terms of size, class served, and entertainment offered.

Ruth Margarete Rollig, who wrote a famous city guide to the Berlin lesbian scene in 1928, remarked, "Here each one can find their own happiness, for they make a point of satisfying every taste."

According to Hirschfeld, some of these lesbian bars could be a little rowdy: he knew of one lesbian cabaret where a performer had been arrested when her act became too bawdy. In general, though, most were as tame as their male counterparts. The atmosphere was generally refined; the lighting was soft and sentimental music played in the background.

One of the most famous was Chez Ma Belle Soeur on Marburger Strasse, decorated in Greek-style frescoes and furnished with private booths, where couples could take refuge behind curtains.

Like the gay bars, many of the lesbian bars were segregated somewhat by class. Nevertheless, part of the excitement of Weimar's lesbian scene was the way that it made contact between previously isolated social groups possible.

Before the war, artists, prostitutes, professional women, and single working-class women had frequently lived in small, same-sex circles that occasionally permitted lesbian relationships to develop within them. In the 1920s a mixing took place between these circles that allowed new opportunities for articulating a sexual identity, one that "suggested linkage across class, gender, and culture."

Gay and Lesbian Balls

Berlin's various homosexual establishments became famous for the elaborate gay balls that they would throw on regular occasions. One French observer of the city around the turn of the century noted that gay balls were held often several times a week in different clubs during the festive season between October and Easter. On some nights, one could even find more than one ball being held somewhere in the city.

At one New Year's ball that Hirschfeld went to, more than eight hundred people were counted. The rooms began to fill as the evening approached midnight; some people were in suits or "fancy dress," but many were in costume. "A few appeared in masks that completely hid their faces; they came and went without anyone having had any idea who they were; others left their cocoons approximately at midnight." Not a few of the men were dressed in women's clothing.

One visitor from South America had on a Parisian dress that cost him a small fortune. Wealthy gentlemen would take the occasion to show off a bit, arriving in elaborate dresses and being greeted with much fanfare. Very often, they would show up and act like a woman the entire night, despite sporting a dashing moustache or even a full beard. Sometimes, though, the costumed men could be more convincing.

On the particular evening that Hirschfeld was there, one of the men in the crowd put on such a successful performance at being a woman that he fooled a police officer who had attended to make sure things did not get out of hand.

After two hours of dancing and parading, the time for coffee came. Long tables were pulled out, and everyone took a seat. Female impersonators danced and sang some humorous songs. And then the evening resumed as before, and everyone stayed well into the morning.

Lesbians sometimes could be found at the male gay balls, and lesbian bars held their own balls. These occasions were different from those of their male counterparts not only in terms of costume, but also generally in their excluding men entirely.

The most exclusive ball in the prewar period was a private party, open only to those with an invitation, arranged by a prominent Berlin lady. Normally it took place in the ballroom of one of the city's grand hotels. Couples would arrive beginning at eight in the evening, costumed as monks, sailors, clowns, Boers, Japanese geishas, bakers, and farmhands. They would sit down to eat at tables lined with flowers; the director, dressed in a "gay velvet jacket," would greet the guests and give a short speech.

After dinner, the tables would be put away, and the orchestra would begin playing waltzes and other lively dancing music while the couples would dance through the night. In a nearby room, others would drink, make toasts, and listen to singing. "No bad moods cloud the universal joy," remarked one female participant, "including those of the last woman participants who leave the place at the dawn's early light into the cold, February morning. It is a place where among people who feel the same way they could dream for a few hours about being who they are inside." *

Excerpt from the chapter "The Growth of Urban Gay Scenes, Berlin's Gay and Lesbian Bars," from Queer Identities and Politics in Germany: A History, 1880-1945, by Clayton J. Whisnant. Available August 2016 from Harrington Park Press, a specialized academic/scholarly book publisher devoted to emerging topics in LGBTQ diversity, equality, and inclusivity. Available on Amazon and Harrington Park Press (distributed by Columbia University Press).

CLAYTON J. WHISNANT is professor of history at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C., where he teaches a range of courses in 20th-century European history. His first book was Male Homosexuality in West Germany, 1945-1969: Between Persecution and Freedom.

CLAYTON J. WHISNANT is professor of history at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C., where he teaches a range of courses in 20th-century European history. His first book was Male Homosexuality in West Germany, 1945-1969: Between Persecution and Freedom.

CLAYTON J. WHISNANT is professor of history at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C., where he teaches a range of courses in 20th-century European history. His first book was Male Homosexuality in West Germany, 1945-1969: Between Persecution and Freedom.

CLAYTON J. WHISNANT is professor of history at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C., where he teaches a range of courses in 20th-century European history. His first book was Male Homosexuality in West Germany, 1945-1969: Between Persecution and Freedom.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella