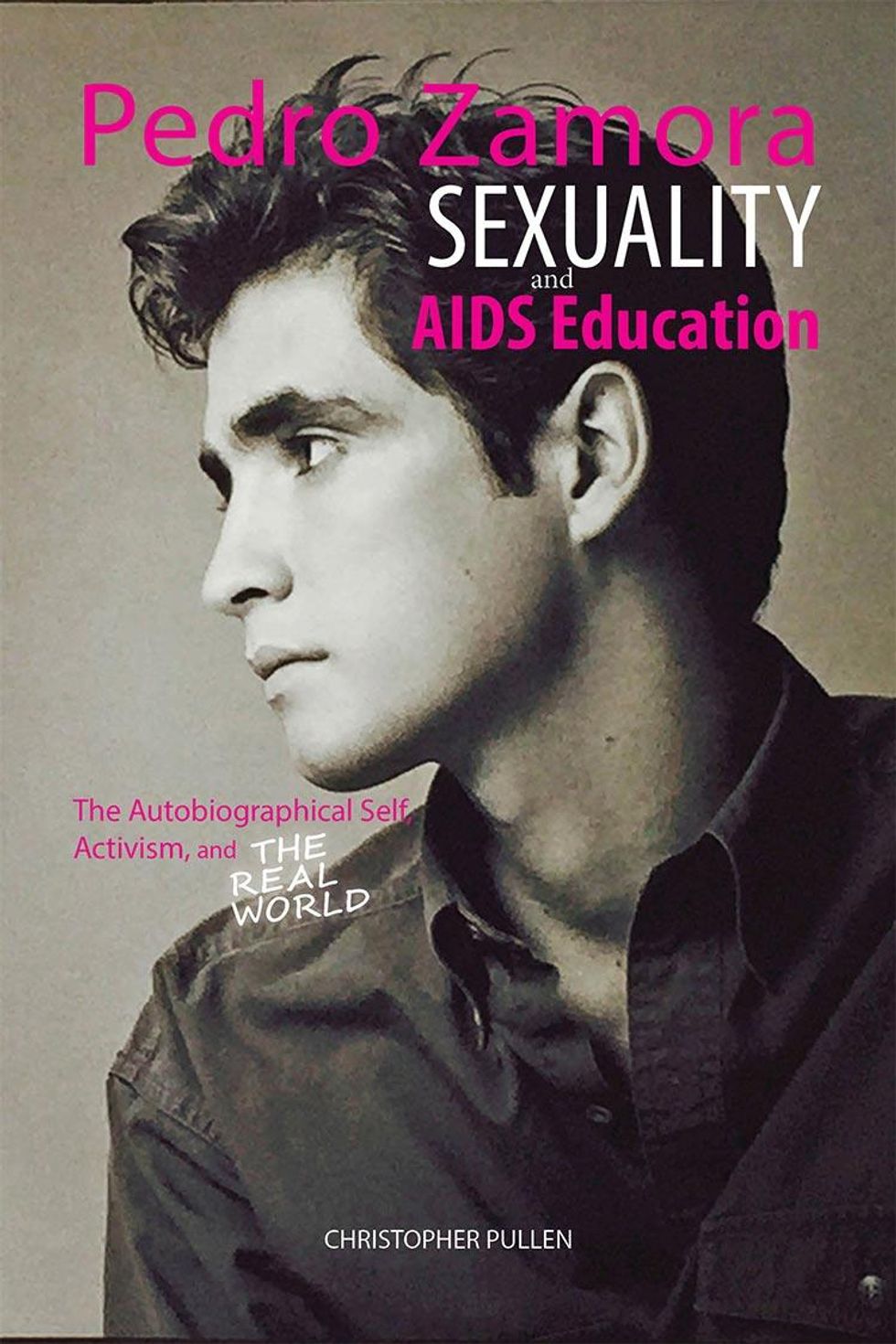

Pedro Zamora was an openly gay AIDS activist of Cuban descent, who became a worldwide media phenomenon, particularly after his participation in The Real World television documentary series, set in San Francisco in 1994, where he openly represented his life as a person living with AIDS, and was coupled with Sean Sasser (who was HIV-positive) as the series romance. Although Zamora died in the same year (at only just twenty-two years old) not long after that the last episode of the series was broadcast, his life story is an important contribution to contemporary debates on AIDS education. At the same time Zamora was an icon for gay male sexuality, highly concerned for the respect and care of "queer" youth. Pedro had an innate ability to reach wide audiences through revealing his honesty, integrity and political vision.

Whilst Zamora did not produce a formal autobiography, he used his autobiographical narrative as a tool for education. This book tells the story of Pedro's life, considering his focus on AIDS education and sexual identity, bringing together diverse research sources, such as newspaper articles, media texts, archival information and new interviews from those that worked closely with him.

Pedro Zamora was an immigrant from Cuba, arriving in Miami in 1980 on the Mariel Boat Lift with most of his family, at the age of eight. When he was seventeen years old, he discovered that he was HIV-positive. Almost immediately, he embarked on a personal crusade to educate the community about AIDS. He became so well-known among the different AIDS education organisations for his work within schools, universities and communities that not only was he invited to take part in advisory boards for health and medical institutional organisations, but also provided formal reports to the government as part of his work. He also became a popular figure in the media -- not only covered in The Wall Street Journal in a groundbreaking article by Eric Morgenthaler and on television talk shows and MTV's The Real World, but he was also a central contributor in AIDS educational documentaries, spreading his message within diverse social environments.

However, it is clear that those who have followed Zamora, such as the recipients of AIDS educational awards in Zamora's name respectively supported by AIDS United and The AIDS Memorial Grove, are not always high profile individuals, but rather "grass roots" contributors to community. This I believe, was the essence of Pedro's message: that people need to work together, respecting each other's interests and goals, not necessarily as role models to the world, but as exemplars to each other.

To follow Pedro's message might involve the need in part for a wider focus on HIV/AIDS in a global sense, and also a need to support vulnerable queer youth in school. Although those with HIV/AIDS are living longer lives in the developed world, at the same time those less fortunate in less developed area such as Africa and Asia are continuing to die in the manner that Zamora did - without the availability of antiviral medicines. The availability of AIDS drugs alone, however, is not the answer. One's personal availability also counts, as active members of community, working together in the service of rendering change.

Zamora was aware of the disenfranchised and isolated experience of queer youth, who often grow up without support from family, peers, or institutions. The rise of queer youth suicides, as reported for example by the It Gets Better Project (an online resource where individuals upload messages of support) reveals the problem of both needing to fit in, and the limited, almost non-existent support for queer youth at school. I believe that if Zamora were alive today that he would want people to work more closely together, rather than to offer advice from our own perhaps more privileged positions. This approach might not rely on celebrity role models or media commentators, but rather on peers, teachers, parents, and members of the community, who function as individual caring social agents and as role models to each other as much as they are to the world.

Zamora's autobiographical message was not one of privilege or distance, as a role model to specifically follow, or unconditionally admire. I believe that his message was a call for action. This might involve sharing life stories, in producing and working through the autobiographies of one's life, not yet completed, but inherently connected to others.

Although I had not heard of Pedro until some time after his passing and consequently I had never met him, strangely I can record a narrative of proximity, which offers a deeply personal resonance. While Pedro had participated in the Eighth International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam in the Netherlands in July 1992, just over a year later in that same city (in late November 1993) my partner and I visited our good friend Roeland De Kuijff in a hospice there. He was dying of complications from AIDS. I recall two vivid impressions. One was of the incredible bravery that he expressed, wanting to make us feel comfortable and welcome in spite of the difficult situation. We accompanied the now painfully thin and wheelchair bound Roeland to a local restaurant. He tried to eat and enjoy food, joke and chat with us even though he was suffering from a host of maladies that we could not have imagined, including (as we discovered) candidiasis that made it uncomfortable for him to swallow. The other impression was the presence of exotic budgerigars and parrots in the park, just near the hospice, in that deepest winter, where the canals were frozen, breath turned to icy mist and the temperature was recorded as -7 C. Roeland explained that these birds somehow had escaped from the safety of households to make their homes in the now seemingly inhospitable park.

While Pedro was in that same city just a few months earlier, clearly healthy and offering support to others in his role as an AIDS educator, Roeland too at that time had yet to succumb to full blown AIDS. Just a few months after our visit, he passed away and we never got to see him again. Unbeknownst to us, Pedro would pass away in the same month that we visited Roeland just one year later. This coincidence offers a deeply personal meaning.

Our memory of Roeland, Pedro, and millions of others lost to AIDS is complicated, seeming to be fixed in time, but also forming part of a continuum of memorial stimulating new understanding. In my view, those confronting HIV/AIDS seem like the adaptable exotic birds in that cold and inhospitable park. Somehow, we all need to fit in and make our way forward, whatever the conditions. This could mean a shortened life, but a time of liberty and freedom might be gained. Our circumstances may lead us to a change in thinking: that any place might be home. The birds, like people with HIV/AIDS or people of sexual diversity, might seem to be trapped outside, but they remain on a continuous and progressive journey. Through this constant motion, potentially they may not need to return to warmer climes or to the comfort of some imagined home, but instead, feeling the liberating air under their wings, make homes with one another, establishing a communion of respect and understanding.

Excerpted from Pedro Zamora, Sexuality and AIDS Education: The Autobiographical Self, Activism and The Real World by Christopher Pullen. Courtesy Cambria Press. Available from Amazon.com.