I didn't always know I was queer -- not everyone realizes it right away -- but I've been wondering where I fell on the spectrum of religious belief since I was a kid.

When I was 11 and just starting middle school, some of my new friends were strongly Christian. I didn't have much of a religious leaning; my mother's family is Catholic and my father's family is Jewish, so I grew up celebrating twice as many holidays but lacked grounding in any particular teachings. So when my new friends told me about a Bible study guide they loved, one that was targeted toward "hip" Christian teens, I thought it would be a neat way to join the youth-group-going in-crowd. As far as I was concerned, I was passively agnostic, but I thought having the tools to find faith might make me feel more certain one way or the other. A friend's mom bought me the trendy teen Bible as an early birthday present.

I was ecstatic to receive it. It was brightly colored, used wacky fonts, and had discussion pages at the ends of some sections, making parallels between Scripture and teen issues like school and dating. But there were some red flags right off the bat that made me think this might not be for me. For example, I'd never had strong feelings about premarital sex, but my friends -- and this Bible -- did. I figured sex would happen when it happened, and between talking with my parents, my lackluster public school sex ed, and Seventeen magazine, I had a decent grasp on how not to get pregnant. My Bible's all-or-nothing take on sex and dating made me uneasy, like a stranger giving me serious advice I hadn't asked for. I didn't even bother looking at the discussion notes on gay people; I didn't know yet that they applied to me. (I recently dug that Bible out from my pile of rejected childhood items to find that section. It's not pretty.)

Then I found something that I took more personally. A small section of the sex and dating chapter included a stern footnote about dating non-Christians. "Don't do it," it said. "It's never a good idea."

I asked my parents about it, about whether or not God thought their interfaith marriage -- and therefore, my existence -- was a bad idea. They said they had talked about it a long time ago and decided that because they both believed in God, the details didn't matter. But it was enough to turn me off of religious exploration for a long time. When I came out as bisexual in high school, I felt even less connected to my friends' stories about church programs and their excitement about applying to Christian colleges. And eventually, I realized I didn't need to explore anymore. The belief just wasn't there.

This isn't to say I disparage or disrespect those who do find comfort in faith. There are thriving communities of LGBTQ people of faith around the world, some of whom belong to progressive houses of worship and others who practice independent spirituality, who find that their faith and their LGBTQ identity strengthen one another. Today, more and more religious groups celebrate diversity, actively support LGBTQ people, and speak out against the institutions that use scripture to oppress and demean. Unfortunately, these groups are in the minority. While there are avenues for LGBTQ people to work with faith groups, the potential for allyship between LGBTQ people and atheists is far more intuitive, and certainly presents fewer institutional boundaries.

When I started writing about LGBTQ issues for Hemant Mehta's blog, "Friendly Atheist" -- which is how this book came to be -- I was often stumped by the lack of news about the explicit overlaps between LGBTQ people and atheists. Stories about active collaborations between these two groups were sparse. All I seemed to read (and write) were stories of outrageous homophobic and transphobic behavior by conservative churches and evangelical politicians, all in the name of God. What I didn't immediately realize, though, is that religious groups oppressing LGBTQ people is an atheist issue. Any abuse of religious freedom, particularly at the expense of a marginalized group, is an atheist issue.

Over and over, LGBTQ people have been berated, belittled, and bullied on the faulty premise that God frowns upon them. This erroneous explanation not only targets LGBTQ people but also contradicts ideas many atheists hold dear.

For example: When a pastor preaches that God unleashed Hurricane Sandy as punishment for same-sex marriage, as anti-gay preacher John McTernan did, that's not just an affront to LGBTQ people; it's an affront to science. When a county clerk cites religion as an excuse to deny LGBTQ people equal treatment, as Kentucky's Kim Davis did, that's a slap in the face to the separation of church and state. And when Christian schools that receive state funding fire LGBTQ teachers, as we've seen across the country, it's a clear abuse of power disguised as "religious exemption."

Science, reason, and a government free of religious influence are some of the most crucial tenets of secular humanism. Atheists -- even those who believe that philosophy begins and ends with a rejection of God's existence -- should be deeply offended when those principles are so egregiously violated.

Atheism itself is still somewhat of a subversive practice. People of faith comprise around three-quarters of the U.S. population; about 24% are unaffiliated or religious "nones," with self-declared atheists making up only 3.4% of the country. There are no openly atheist members of Congress. In some countries, being an atheist, being LGBTQ, or both are cause for persecution or even death. And, of course, there are LGBTQ atheists in the United States and elsewhere who are doubly marginalized for identifying as both. It is in atheists' nature to eschew societal norms in favor of ideas that feel more true to them. Joining forces with others targeted by religious groups shouldn't be controversial. In fact, it should be expected.

Some people -- though not usually atheists -- actually argue against taking religion out of politics, citing the civil right to free expression. And sure, the First Amendment has its place in these conversations. A person who pushes homophobia or transphobia under the guise of religion is allowed those opinions privately and even publicly, to an extent. But once religious beliefs are invoked to interfere with the civil rights of others -- say, to justify firing a qualified employee, or to provide a legal loophole for segregating LGBTQ customers -- the First Amendment exits the equation. Personal beliefs cannot infringe upon the rights of others to pursue life and liberty however they choose. If atheists sit idly by as religious Americans target LGBTQ communities, they are endorsing it.

And yet America's failure to protect LGBTQ citizens is a direct result of the overstepping of religion into politics. It's a flagrant rejection of the Establishment Clause, and a refusal to prioritize objectivity and fairness. Equal rights for LGBTQ people should come naturally to a society that operates on evidence and reason (the kind of society atheists generally advocate for). Atheists should be invested in removing religious influence from the rule of law. And they do their own cause a disservice when they fail to defend LGBTQ people, politically and personally.

As both an atheist and a queer person, I'm doubly baffled by the intensity of religious hatred against my people -- all my people. I write a lot about LGBTQ issues, and I've received countless anonymous messages (and some not anonymous) outlining all the reasons I'm a hellbound dyke. Sometimes, the message is just a list of Bible verses -- as if I'm going to take out my copy of the New Testament and flip through it to learn why my life displeases a higher power whose existence I reject. I'm lucky to have lived mostly in liberal parts of the country (not that religious bigotry doesn't exist in all 50 states) and that I've never faced faith-based discrimination outright. But thousands of others aren't as fortunate.

LGBTQ people are fired, kicked out of their homes, pushed out of local businesses, and refused social and health services because of the "religious consciences" of others. To make matters worse, we don't even know exactly how many LGBTQ people face discrimination every year. As in other situations when victims must choose whether to report what's happened to them, many people refrain out of the fear of retaliation, outing, or worse. (And just because it hasn't happened to me yet, there's no guarantee that it won't in the future.)

LGBTQ people and atheists aren't the only groups hurt by religious fundamentalism. For example, the Religious Right targets women with a similar fervor. Employers fight to deny insurance coverage for birth control on the grounds of religious freedom. Women are fired for being pregnant and unmarried. Puritanical beliefs about women's rights and roles trickle down into other elements of society. The wage gap and sexism in the media aren't necessarily a result of religious misogyny, but they're peddled by a lot of the same people.

And historically -- though not long ago at all -- people deployed religious arguments to defend segregation and other manifestations of racism. "In the 1960s, we saw institutions object to laws requiring integration in restaurants because of sincerely held beliefs that God wanted the races to be separate," according to the ACLU. Integration was seen as an affront to God. Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist Protestant school in South Carolina, didn't drop its ban on interracial dating until the year 2000.

When you consider how extreme the consequences of bigotry can be, the harassment and disrespect atheists face for their non-belief can seem pretty mild in comparison. Society certainly doesn't embrace atheists, but there are far fewer attacks (physical, legal, and otherwise) on atheist "lifestyles" than on LGBTQ people, women, people of color, or even other religious groups. But plenty of atheists can be and are members of all these groups, facing attacks not for their non-beliefs, but for visible elements of their identity. Virtually every minority group in the world has faced some defamation, discrimination, or mistreatment at the hands of religious extremism, one way or another. It only makes sense that we would rally together in our respective times of need.

Why LGBTQ people in particular? Because when it comes to religious suppression of civil rights, LGBTQ people have too much at stake. In recent years, the Religious Right has focused much of its energy and resources on limiting -- or even eliminating -- the rights of LGBTQ people. Anti-LGBTQ ideals littered the 2016 Republican Party platform and continue to serve as talking points for many GOP politicians, even though religious beliefs are supposed to be absent from the legislative process. According to the Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBTQ rights group in the country, only four Republican senators and seven Republican members of the House of Representatives supported marriage equality in the lead-up to the 2016 election. Even Barack Obama, arguably the most progressive president in U.S. history (certainly on this issue), didn't announce his support for marriage equality until the end of his first term, after a handful of states had already enacted same-sex marriage and Proposition 8 had twice been ruled unconstitutional.

LGBTQ issues have never been more visible, and anti-LGBTQ religious extremists have never been more fired up. If equal rights advocates don't fight back aggressively, we can expect sweeping victories for state-approved religious bigotry. That kind of upheaval would deal a significant blow to atheism, too: imagine trying to defend secular education, the scientific method, or the separation of church and state in a country that explicitly favors one belief system over others (let alone over non-belief). We may be a long ways off from falling into an extremist religious dystopia, but it's still worth keeping our guard up.

And it's not enough for atheists and LGBTQ people to be allies in name alone. In order for both these groups to be treated with civility and humanity, we must support each other loudly and unapologetically, in our schools and our workplaces, at the dinner table and at the ballot box. In 2015, atheist writer Adam Lee penned an editorial for the Guardian with the headline, "If peace on earth is our goal, atheism might be the means to that end." While that sentence might suggest a simplistic answer to a complicated problem, there is little evidence for more religious influence leading to social harmony. LGBTQ people have been political targets for decades. As society slowly begins to see us with more empathy than ever before, we deserve the peace we've been denied for so long. Atheists must help us get there.

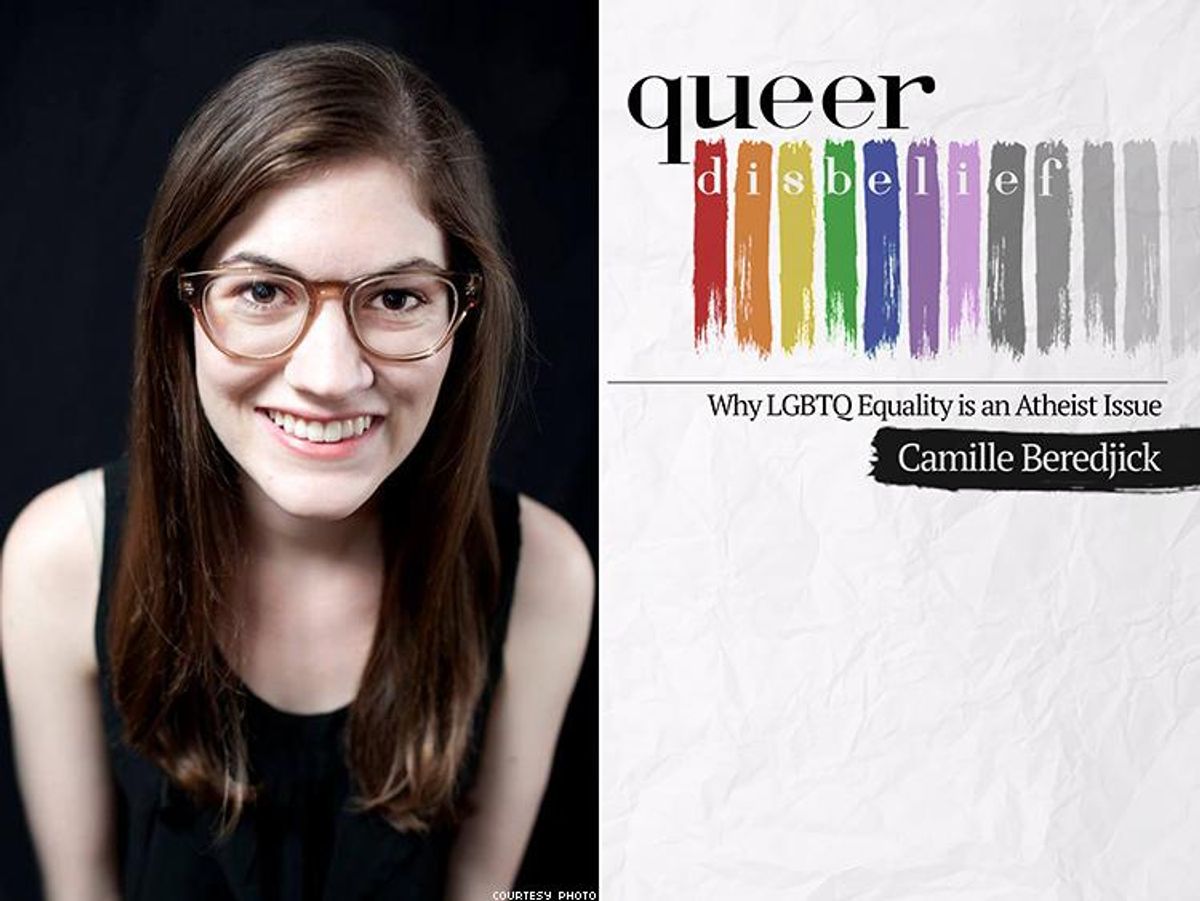

A Kickstarter campaign is currently underway to help fund this book's formatting and printing, tweaking the cover design, and helping with shipping and packaging fees.

CAMILLE BEREDJICK is a nonprofit social media manager by day and a writer by nights, weekends and lunch breaks. Queer Disbelief is her first book. Beredjick has worked as a communications and digital media specialist at nonprofit organizations throughout New York City. Her work has focused on issues including LGBTQ rights, bullying, HIV/AIDS, PrEP, sexual assault, and domestic violence. Beredjick is the editor of GayWrites.org, a daily blog where she covers LGBTQ news, media, and culture for an audience of more than 200,000 subscribers. Her writing about LGBTQ rights, politics, health, identity, and other topics has appeared in The Advocate, In These Times, BuzzFeed, Time.com, Mic, Daily Dot, HuffPost, Patheos and the Establishment, among others.