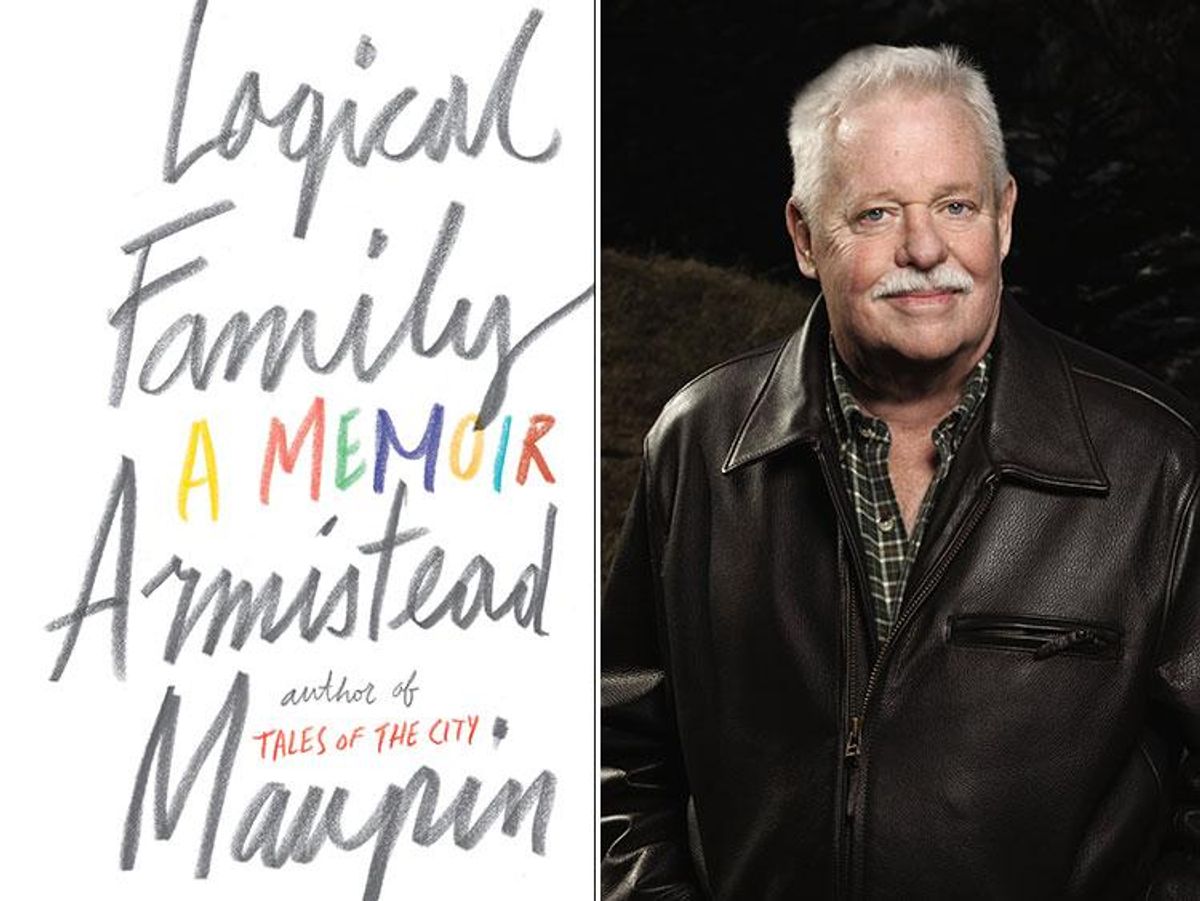

As a young man, Tales of the City writer Armistead Maupin worked briefly as a reporter for WRAL TV, a station in North Carolina. The following is an excerpt from his new memoir, Logical Family, which details a memorable interview from that experience.

That summer at the television station remains largely unmemorable except for the time that the newsroom sent me to cover a Ku Klux Klan rally in a tent on the edge of town. By then, the Klan had become an embarrassment to many white Southerners, even the ones, like my father, who still defended segregation.

"They're just a bunch of crazy folks," he said, "and common as can be. It's not like it was during Reconstruction when there were gentlemen under those hoods. Plantation owners and such. They needed it then to keep the n****rs and carpetbaggers in line."

I don't recall there being hoods at this rally, just a lot of overalls and blue serge suits and a smattering of robes with gaudy insignia. It felt more like a revival than anything else, and the Imperial Wizard had the leathery, rheumy-eyed look of a country preacher. Pressed for something provocative to ask, I brought up Peggy Rusk, a young woman whose wedding photo had just appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Peggy Rusk was the daughter of Dean Rusk, Lyndon Johnson's secretary of state, and her groom, a recent graduate of Georgetown University, was African-American. Only three months earlier the Supreme Court had struck down Virginia's ban on interracial marriage, declaring marriage to be "one of the basic civil rights."

The subject was topical, to say the least, and I figured the Wizard would have something quotable to say about it. He seemed to be composing his thoughts, so I signaled the cameraman and leaned in with the mic. This could be my first big story.

"Well," began the Wizard, "I don't think anyone should be even slightly surprised."

And how was that?

"Because Dean Rusk is a liberal. He's one of the most liberal men this country has ever seen. Naturally he would've approved of this marriage. And his daughter must have been raised to think that way. To think there was nothing wrong with it."

This was disappointingly reasonable for my purposes.

"No sir," the Wizard continued. "I think that's exactly what you should expect from the daughter of a man who's a practicing homosexual."

I stood there dumbstruck until the cameraman nudged me to indicate it was my turn to say something. I cleared my throat to buy time, then began: "You're saying that the secretary of state is . . . um--"

"Yes sir. That's exactly what I'm saying."

I drove back to the station with a racing heart, thrilled that I had a story so big that it might go national in a matter of days. Somehow, in the name of the almighty scoop, I had completely disconnected from my own reality. It's possible, I suppose, that I saw this story as a smokescreen. I had already learned the cowardly trick of mentioning homosexuality with a tone of amused and tolerant detachment.

Normally, I would have gone straight to the newsroom when I had a story to write, but I couldn't resist the urge to brag to my boss, the commentator. I spilled it out in the door of his office. He stared at me for a moment then took off his glasses and began to clean them with a tissue. He told me to come in and shut the door.

I obeyed, but I didn't sit down. He had a very grave look on his face. "We can't run that story, son."

"Why not?"

He returned his glasses to his face. "Because it's libelous. The station can get sued from here to Kingdom Come."

"But we're not saying it. The Imperial Wizard is. I have it on film." His mouth hitched to one side, revealing that dull pearl of froth inthe corner. "Dean Rusk is a terrible, terrible fellow, I'll grant you that. But we can't say that about him. That's the worst thing you can say about anybody. It's an abomination."

It was awkward for him to get that long word out of his off-center mouth, but he said it more earnestly than anything I had ever heard him say.

"You understand me, don't you, Armistead?"

I understood all right. This was deeply personal to him. He cared about this subject in a way I'd never heard him care about anything. His usual response was to become red-faced in times of serious agitation, but now he had turned deathly pale. I found it disturbing in a way that I couldn't define.

What happened to him? I thought.

I'm certain he had no idea about the abomination standing right there in front of him. As far as I know he didn't learn about me until ten years later, when I finally came out in the most irrevocably public way I could manage -- in Newsweek magazine. By then my former boss would be serving the first of five terms in the United States Senate, where he was already becoming known as the nation's most rabid opponent of gay and lesbian rights. He called us, among many other things, "weak, morally corrupt wretches." Though he never paid me the honor of naming me--that, no doubt, would have been impolite to my parents -- I condemned him publicly on a number of occasions, most notably perhaps on the steps of the North Carolina State Capitol at the conclusion of Raleigh's first Gay Pride March in 1989.

Several years later I returned to WRAL-TV on a book tour. The female half of the nightly news team was one of those lazy, tell-us- about-your-book spokesmodels that touring writers come to know all too well. (In those days I never got the male anchors; they weren't comfortable being seen with men who loved men.) So, when my chirpy interviewer slipped into cookie-cutter mode about my novel, I decided to use the airtime for my own amusement and volunteered some useful information:

"You know, I used to work here."

"Really? In Raleigh, you mean?"

"No. At this very station. I was a reporter."

"Well, isn't that a hoot?"

"I worked here when Jesse Helms was here. Now he's in Washington, ranting about militant homosexuals, and I'm out running around being one."

No response.

"Life is interesting, isn't it?"

Somehow the poor thing got to the commercial without losing it completely. I was supposed to be given a full six minutes, but they showed me the door as soon as the camera was off and brought on an adoptable puppy from the Wake County SPCA -- the very organization that my late mother had founded.

My mother and Mrs. Jesse Helms.

ARMISTEAD MAUPIN is the author of Tales of the City. His new book, Logical Family: A Memoir, recounts his conservative upbringing and his journey toward becoming a prominent chronicler of the LGBT community.