In January 1978, driven by a longing to find home in the big sense--a place of belonging that I returned to every day, where people loved and counted on me, a place signifying permanence--I bought a house with Linda and moved in with her and her two children.

Coming out was one thing, but coming out like this was far beyond my knowledge and experience level. I had barely claimed my identity as a gay woman, and now I was about to become a gay parent. The term "blended family" had been coined just a few years earlier, but in 1978, it didn't mean this blended. The powers that be would consider this more of a scrambled family, and not in a good way.

Custody cases favored the father if the mother was known to be in a relationship with a woman. Anita Bryant was still on a soapbox declaring that gays and lesbians were threatening to our children. She clearly hadn't thought about the fact that most gay people were the products of heterosexual coupling and had grown up in heterosexual households. In vitro fertilization was only in its experimental phase. Perhaps she should have worried more about straight people. Masters and Johnson were in support of "conversion therapy" for homosexuals, asserting that they could all be "fixed." It was not a comforting environment in which to announce your bonding preference for women, let alone that you were in a super-blended family.

Soon I would learn that being a parent was harder than being gay. Having never babysat or changed a diaper or listened to a child scream for three hours at a time, I was completely outside my comfort zone--piloting a space shuttle to Venus would have been less daunting--and if the children hadn't been in equal portions as charming as they were exasperating, I wouldn't have made it past the first month.

As it turned out, they became two of my most important teachers about what it means to be family and for people to count on you. This was first poignantly illustrated in a series of conversations with Sara over several weeks, during drives in the car. By now, Molly was two and Sara was four. I often picked the kids up from preschool, and, long before the day of car seats, Sara would stand up in the back as I drove, usually to reprimand me for going twenty-seven miles per hour in a twenty-five miles-per-hour zone. But today she had something else on her mind. Standing up, she leaned over the front seat and, seemingly unprovoked by anything other than her own thoughts, addressed me in an authoritative voice:

"You know, Carol. You're not a part of our family."

Thanks for sharing, I thought. Since it was far from easy to take up family life as a lesbian, it was good to be put in my place by a four-year-old who made it quite clear I didn't belong there. We got home, and she asked me to cut her some salami for a snack, oblivious to my hurt feelings.

Time went on, and a week later, as I was again driving the kids home from school, and Sara, taking her usual place standing in the back seat, leaned over and said, in a more invitational tone, "Well, Carol, since you live with us, why don't you be a part of our family?" She shrugged her shoulders as though saying without words, Doesn't this seem like a reasonable thing to do?

"Sara, I would love to be a part of your family; thank you for that lovely offer." We got home, and she skipped off to play with some friends--nothing more was said about it. I sat down on the couch bemused by her comment and curious about how her thinking process had unfolded.

A few days after that, Sara and I were again driving in the car when, from her usual place, she leaned into the front seat and, in an excited voice that revealed pride in her ability to reason, said enthusiastically, "Since you live with us and are a part of our family, we should change our names to the Anderwetts!" My last name being Anderson and theirs being Hewett, she had figured out a way to merge the two and make up a new name that would formally show that we belonged together.

"That's a fabulous idea, honey," I said. "We will have to discuss it with your mom at dinner."

About a week later, when Linda and I had driven separately to visit my mother for dinner in Plymouth, Sara said she wanted to ride home with me and suggested that Molly go with her mother. We got in the car, and Sara, now buckled in the passenger's side, said eagerly, "C'mon, Carol. Let's race them home."

"That's a great idea," I said. "And I know a shortcut." I stepped on the gas, and off we went. I cut down a side street and flew as fast as the speed limit would allow. "Hang on; we're going to make a sharp turn." Sara squealed with glee, looking over her shoulder to make sure we had lost them.

"Faster, Carol, faster!" The pitch of her voice rose at every turn as she cheered me on for thirty minutes all the way home. Both of us overjoyed as we screeched into the driveway ahead of her mother and Molly, Sara blurted out, "You're the best, Carol! Why don't you and mom get married?" It was 1978, and even the shadow of such a possibility was so remote from our consciousness that no one could imagine that option in our lifetime. Yet a four-year-old had somehow, in the course of several weeks, processed the idea of home and connection and family and marriage as a totally natural conclusion for any group of people who lived together and who loved each other.

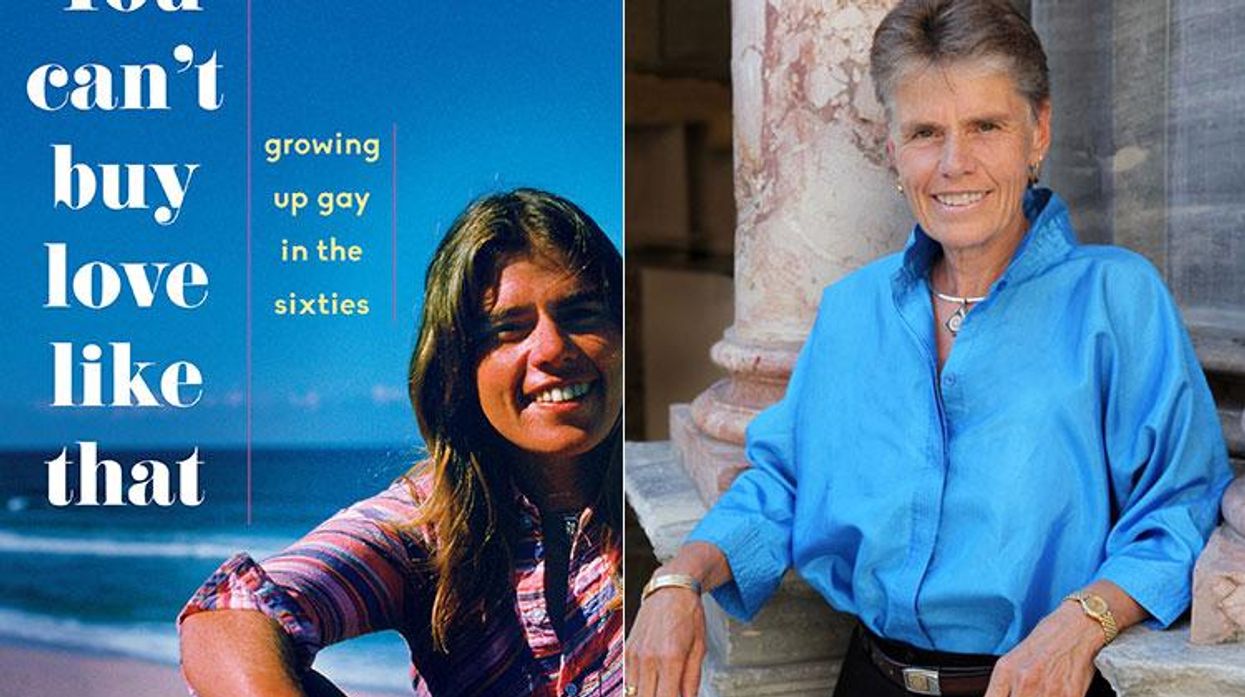

Excerpted from You Can't Buy Love: Growing Up Gay in the Sixties by Carol Anderson. Published with permission from She Writes Press.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes