Angela Calomiris took her time emerging from the closet as informant/witness. Vague rumors about government connections and stories about famous people she had known made the rounds in the gay community. But no one came forward with significant details until the 1980s, more than thirty years after Angie's appearance on the witness stand. The McCarthy era spawned great controversy--and especially bitterness toward informants--and was generally not a topic for conversation. An older lesbian who had known Angie well in the homosexual underworld of Greenwich Village finally broke the silence, but quite by accident and unintentionally. She was Buddy Kent (aka Bubbles Kent, Exotic Dancer, aka Malvina Schwartz of East New York, Brooklyn) who, like Angie, had lived in the Village since the late 1930s. In an interview with gay historians, Buddy touched on a variety of topics about a time when unconventional people--artists, Bohemians, political radicals--flocked to the Village, and lesbians felt safe from catcalls and threats of violence. But it was also a time when identities were closely guarded, when silence and loyalty were community values. Not unlike other secret and semi-secret societies (the Mafia, the American Communist Party), the less outsiders knew about the gay world, the better, particularly sworn enemies like the police. While gays threatened with exposure at mainstream jobs were routinely blackmailed right up until the Stonewall uprising, as an entertainer working in drag shows in downtown nightclubs of the 1940s (the 181 Club, 181 Second Avenue at East 12th Street, and the Moroccan Village, 23 West 8th Street), Buddy Kent had the advantage of the best in protection from the Mafia that owned and ran those establishments.

Buddy did not intend to name names, in fact she never did. Instead, like a mystery writer, she wove a series of clues into her recording with Joan Nestle, co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, who conducted the interview. Sharing old photo albums (now lost to history), Buddy mentioned several gay friends and acquaintances long dead, which was permitted if they had been dead long enough. She added a few observations about Eleanor Roosevelt in the Village before Joan asked her, "Who else would you see in the street sometime, or hanging around here [the Village]?"

Buddy didn't hesitate. Remembering stage and screen personalities she had known, celebrities whose names still resonated with a contemporary public, she began, "Not too much theatricals, 'cause they were afraid then. But Judy Holliday ..." Buddy paused. She had named one of the brightest screen stars of the 1950s, who had won an Oscar for Best Actress as Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday, a role Judy had created on the Broadway stage. Other nominees that year included Bette Davis for All About Eve and Gloria Swanson for Sunset Boulevard. Judy Holliday (nee Judith Tuvim) was a big moneymaker for the irascible President of Columbia Pictures Harry Cohn, and her reputation had to be protected.

The plot thickened when Buddy added, her voice a bit altered, "She was going with a female who was a cop." This was not idle Village gossip. Other sources, Boze Hadleigh's Hollywood Lesbians among them, suggest that Judy Holliday went through a lesbian "phase" before she "discovered" men, married David Oppenheim, and gave birth to her son Jonathan. Of course, Judy was no longer a teenager when, according to Buddy, she was "going with a female who was a cop."

This brief foray into Judy's love life was followed up by more sensational gossip about her unnamed girlfriend/lover. The girlfriend had her own story, Buddy explained, because "somebody blew the whistle on her being a Communist. And she had quite a bad time. She couldn't get work for about eight years because of this."

"Was this in the fifties?" Nestle was quick to respond, "during the McCarthy period?" These would have been serious charges at a time when the hunt for Communists, former Communists, and Communist sympathizers ("fellow travelers") was at its height.

Significantly, Buddy pushed the date back a bit, trying to pinpoint the events she had described. "During the war, I think," she replied. "1946, yeah, '46." Then, a little fuzzy on chronology, Buddy jumped ahead to the events that defined the Red Scare for most Americans of her generation--the trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the "Atomic Spies," convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage.

"Everything was with the Rosenbergs," Buddy said. "What year was it with the Rosenbergs? That was about the era. With the spy case."

While Buddy may not have been political in the larger sense, within the closeted homosexual world of the Village, she did take a stand on principle-- the one about not informing on gay people. Returning to the betrayal of Judy Holliday's girlfriend, Buddy struggled to temper her anger with compassion. "And it was a gay girl who blew the whistle," she blurted out. "In fact, I wasn't friendly towards her until quite recently. 'Cause I figure you can't have somebody wear a hair shirt the rest of their lives. 'Cause everybody's allowed one mistake in their life."

Careful not to name anyone still living, neither the informer nor Judy's girlfriend, she added, "In fact she [the informer] is around today and I don't want to mention her name. [...] But it meant some good jobs for her [the girlfriend] and even though she turned, you know, turncoat." It seems significant that Buddy considered the "turncoat" less morally reprehensible than the informer who denounced her. Nobody liked a snitch, as Victor Navasky reminds us in his classic blacklist history Naming Names, and the snitches did not seem to like themselves much either.

Listening to Buddy Kent's interview, one has to wonder who the unnamed informant might be who had laid waste a career ("a female who was a cop") with the New York Police Department, which had offered few real opportunities to women before the late 1930s. Buddy described the stoolpigeon in different terms when she summed up: "And there was 'Petite Feminine Girl on Stand Tells Her Undercover Work for the FBI.' And that was this dyke who put the finger on one girl who was on the police force and she was going with Judy Holliday. And she [the girlfriend] never really came out of it well. She was in therapy after that."

By adding newspaper headlines and a courtroom context, Buddy deepened the mystery. When did the FBI hire lesbians to work undercover? And if this one had made headlines when she appeared in court as a witness, what had she been witness to?

Without a name for the informer (or the girlfriend) their secrets were safe. By chance, it was Victor Navasky who provided information that brought everyone out of the closet. Early on in Naming Names, he mentions some "confidential informants" who reported on Communist Party activities to the FBI, and cites two who "surfaced to testify in the key 1949 Smith Act trial in Foley Square." One was an Angela Calomiris, whose name Navasky repeated, and quoted extensively from Red Masquerade, the book she had published about her undercover work. He listed other informant/witnesses who had written books, too, about their brush with the Red Menace, and sold their scripts to radio, TV, even the movies. "Angela Calomiris," he writes, "a witness in the Dennis trial, won a citation for patriotic assistance to the FBI."5

Navasky struck a resonant chord. That name Calomiris, Angela Calomiris. It was that name, and Buddy Kent on tape, out of the blue changing the subject, volunteering:

You know Angie Calamares [as Buddy pronounced it] has started coming to our socials. [...] Fell in love with SAGE [Senior Action in a Gay Environment]. I kept telling her 'Come, come.' She says, '... That cornball shit.' I said, 'No, no, Angie, you'll like it. It's really not ...' She was there till the last one. She had a ball.

Calamares, Calomiris, Angie, Angela. Maybe Buddy Kent had revealed the name without meaning to. She would have welcomed a new supporter (Angie "Calamares") to the SAGE socials, but she could not forget that this was also the FBI informer who had made accusations against Judy Holliday's girlfriend.

At that time, in 1983, there were many people around who remembered. Others confessed that they had known "an Angie Calomiris." "Oh, sure, but I didn't like her," said Miriam Wolfson, who once lived on West 4th Street in the Village. "She was very mannish." When Wolfson was confronted with an ancient copy of Red Masquerade: Undercover for the F.B.I., purchased online, she quipped, "Angie wrote a book? You gotta be kiddin'." The masquerade in the title was Angie pretending to be a Communist in order to spy on them. A second masquerade would have been pretending to be straight in order to pull all that off. When Miriam was offered a passage or two to read from Red Masquerade, she observed, "She's talking about picking out the right dress for the trial and doing her hair. That would be the only time she ever wore a dress!" In another interview, Morry Baer, who had worked to retirement for the New York Police Department, said she had no idea how or why Angie had gotten involved with the FBI. "She didn't talk about it." Morry paused. "You know she ran Angel's Landing in Ptown for years. We used to go up there."

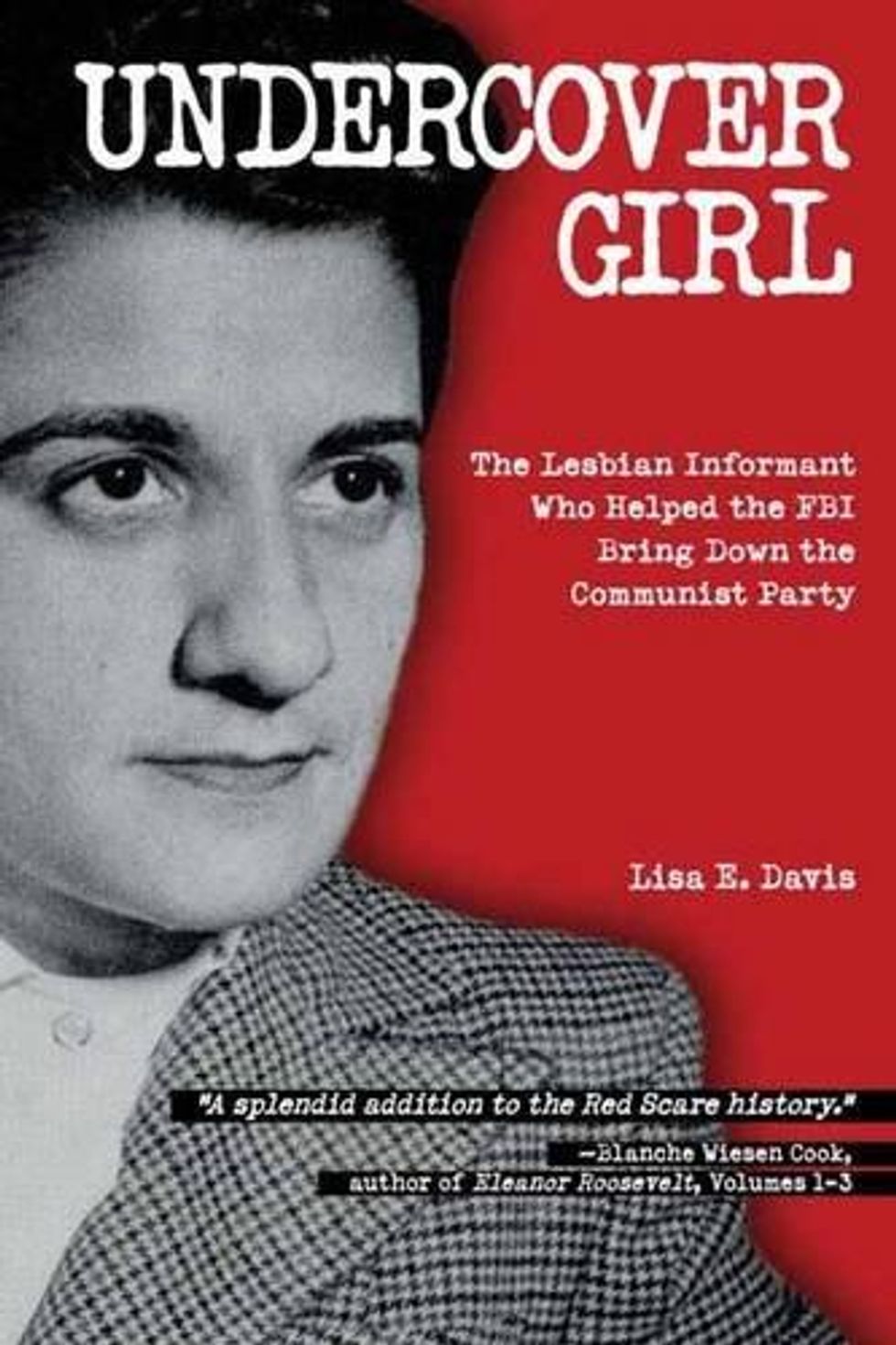

Excerpted from Undercover Girl, courtesy of Imagine.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes