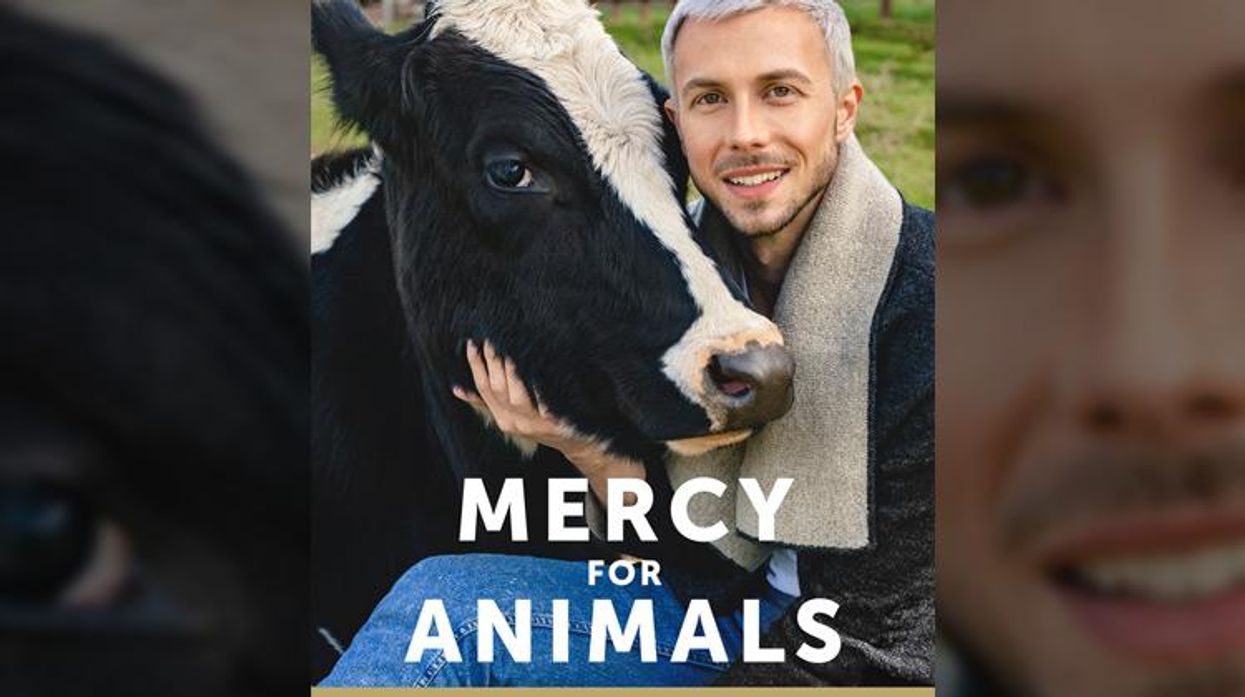

At the same time as I was leading Mercy For Animals, I had been growing up -- or at least, trying to. Physically, I had shot up from an undersized boy to a nearly six-foot-tall teenager. Emotionally, I was struggling to understand who I was, much less where I was going. When I was young, I'd been fully aware that I was different from other kids. I never fit in at school. This was one reason I was home-schooled, and why I never considered going to college. With my heart set on helping the only real friends I had -- animals -- I felt as though those four years of study could be better spent in the real world mastering the ropes of activism. MFA felt like my child. I knew it needed constant attention to grow and mature. If I abandoned it for college, it might well wither and die. Besides, there was no such thing as a Bachelor of Science in Animal Advocacy.

It was time to hone my craft and build my organization; to do that, I decided I should apprentice myself to the largest and most famous animal rights organization in the world: People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA. Established in 1980, PETA was co-founded and run by the British-American animal- protection advocate Ingrid Newkirk.

For three years, starting at age 15, I split my time between nurturing MFA and working directly with PETA. I traveled around the country with senior staffers to help them coordinate and lead scores of always eye-catching (and often controversial) demonstrations. For example, in the summer of 2000, one of my mentors, PETA vice-president Bruce Friedrich, asked me to go to the Southern Baptist Convention in New Orleans. The mission: dress up as Jesus and hold a sign reading "Blessed are the merciful--Go vegetarian"...all day, every day of the three-day convention. The atmosphere was hot, humid, and hostile. The Baptists kept approaching us and reading us quotations from the Bible-- proving, they said, the spiritual virtues of eating animals. It was exhausting and frustrating, and I didn't make a very convincing Jesus.

After the second day, I told Bruce I'd had enough. So he put me in a chicken costume. Going from Jesus to a chicken was a good move. The costume was hot, but I preferred heat stroke to hearing all these people tell me that Jesus wanted them to eat meat.

Not far from us a group of gay activists was practicing civil disobedience. One by one, they would walk peacefully up to the entrance of the convention center, try to go in, and be refused entry. They were then arrested, one after another. I started crying inside my chicken costume. I was so moved by these people, all willing to stand up for, and be arrested for, gay rights. Standing up for me, at a time when I wouldn't stand up for myself.

Inspired by what I learned at PETA, I began organizing and leading more colorful protests of my own. In the freezing Ohio winter, I led "I'd Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur" protests. As the campaign slogan implies, the demonstrations center on a stunt: stripping naked in public to protest fur sales. The idea is you'd rather wear nothing at all than support an industry that profits off gassing, trapping, clubbing, and skinning innocent animals alive for their pelts. I was too young to strip down myself: The law forbade it. So I convinced others (including my brother-in-law, a buff all-American football player) to shed their clothes and stand out in the snow in their underwear. Covered only by a vinyl banner bearing the campaign slogan, my partners in activism stood there for hours with their lips turning blue and their bodies nearly going into shock. The outrageous stunts (performed all over the country, not just by my little crew) proved successful, generating national headlines. We were putting the issue of animal cruelty in the fur industry on the public radar right as the holiday shopping season was about to begin.

Another time, during a 2001 campaign to pressure Burger King into adopting minimal animal-welfare standards, I was dispatched to a local elementary school along with Caroline, a 65-year-old volunteer stuffed into a brown cow costume. The mission: distribute bloody "Murder King" crowns to kids as a media stunt. The crowns featured images of bloody, dead animals impaled on the crowns' golden spikes. The stunt lasted only minutes, but did the trick. Parents, teachers, and the principal weren't happy, but the press loved it. They swarmed Caroline and me as the kids grabbed the crowns. That night, every local TV station carried the story. They also aired graphic undercover footage: cows hung upside down at slaughterhouses, chickens crammed in cages, and pigs locked in stalls at Burger King suppliers. A few weeks later, Burger King agreed to make changes.

Then there were the naked tiger women. I was traveling the country with PETA, standing anywhere from the front lawn of the White House to downtown intersections in cities from Memphis to Los Angeles. We were shadowing the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus, showing up a week before they did in each city. The goal: to get people thinking about the miserable lives endured by tigers, elephants, and other animals held captive by circuses. These animals were not only forced to perform unnatural acts, but also "trained" to do so using violence and intimidation, their spirits broken by beatings and deprivation.

My job was as makeup artist: painting naked women up as tigers. First I'd brush on a solid coat of orange paint, followed by the all-important black stripes. A black nose and whiskers topped off the look. I traveled with the painted tigers to each protest location, helped them disrobe, and then lowered a small, makeshift wire cage over them. I'd hold up a banner behind them reading, "Wild Animals Don't Belong in Cages. Boycott the Circus." Once again, the protests captured the media's attention (as well as the interest of creepy men hoping to catch a glimpse of naked women). Every now and then, the authorities would arrest one of the naked tigers for indecent exposure, leaving me to speak with the press, deal with the cops, and bail the tiger out of jail.

As I said, these tactics were controversial. That was the point: to grab the attention of the media and public just long enough to get people to consider the plight of animals on factory farms or in circuses. We didn't care what people thought of us. We cared that they thought about the animals they were eating, wearing, or exploiting for entertainment. And it worked.

So while other teenagers were stuck in classrooms studying textbooks and taking notes during lectures, I was already out in the world, having dived headfirst into working for social change. I was learning complicated adult lessons in activism, campaign strategy, public relations, mass media, and corporate relations. And I was able to travel around the country, even if that sometimes meant seeing it through the eyeholes of an animal costume.

Reprinted from Mercy for Animals by arrangement with Avery, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright (c) 2017, Nathan Runkle/Mercy For Animals.