Rounds was one of the current hustling hot spots, a scene that had changed little since my libido took a hike after my mother's death. Two very different bars served as two very different backdrops. The climate and clientele in Rounds, the elegant, handsomely designed and softly lit bar in the East Fifties, was light years away from the other central emporium, the down-and-dirty West Forties hangout, Haymarket. Urban renewal hadn't yet hit the Times Square area -- its shaky start would begin in 1981 -- and Haymarket, compared to Rounds, had a tenser ambience, terser conversations, tougher young men -- and lower prices.

Even some of the Bloomingdale regulars who frequented Rounds would now and then drop in -- "in a fit of madness," they liked to say -- to savor Haymarket's "adventurous" climate. Haymarket in turn seemed a fortress of safety when compared with Forty-Second Street itself, which, pre-" renewal," still retained its ancient character as a hub of illicit activity, ranging from high-risk street pickups and drug deals to a cornucopia of peep shows and porn theaters.

One evening some years earlier, when Dick and I were due to rendezvous at Haymarket, he arrived with Gore Vidal in tow, along with Gore's amiable, unassuming companion Howard Austen. Dick had known Gore rather well for some time, but (my memory's shaky here) that night may have been my first encounter with him -- though thereafter our paths occasionally crossed. At the time I was working on my play about the Beats, Visions of Kerouac (one of six plays the Kennedy Center had commissioned for its Bicentennial celebration), and knew that Gore and Kerouac had hopped into bed at some point. Always the diligent historian, I promptly asked Gore how big Kerouac's cock was.

"Average size," he urbanely replied, not missing a beat. "But what surprised me was that he was circumcised -- the Lowell working class isn't supposed to do that."

When I pushed for more details, Gore -- with trademark hauteur and no apparent irony -- obliged:

"I felt he and I owed it to American Literature to go to bed together." A look of mild disgust passed over his face: "We only 'belly-rubbed.'" (Dick later told me, true or not, "Vidal is almost never interested in anything else.")

Perhaps inspired by the cash-and-carry atmosphere of Haymarket, Gore then proceeded to claim that

"a man named Kelly used to pay Kerouac and Cassady to have sex together while he watched and jerked off. As you must know," he loftily concluded, "Kerouac was mostly homosexual, Cassady mostly trade."

The conversational gambits at Rounds were in general more mannerly and indirect. Assured young college students (for which substitute incipient filmmakers, struggling actors, aspiring rock stars) mingled with unembarrassed ease among snottily elegant, conspicuously successful older men. Hustlers and Johns were often indistinguishably fashionable in dress and indistinguishably glib at banter. To be sure, some traditional gauges still prevailed to separate youth from age: skin texture, hairline, muscle tone (tightness of buns being the critical differentiation).

Yet not even these distinctions were any longer infallible, thanks to the ubiquitous use of Nautilus machines and the marvels of modern cosmetology. The tight young look-alike bodies poured into designer jeans and open-neck Armani shirts that came in and out of Rounds concealed far more diversity than was immediately apparent. Yes, there were college students and out-of-work actors aplenty, many of whom, on cue, would subject you to some variation of "I don't regard hustling as any big deal. I simply decided it made much more sense to sell my body for a few hours every week and spend my time working on my craft rather than doing some stupefying nine-to-fiver."

But there were many others who might dress the part of upwardly mobile youth but disdained its class manner. On my very first foray to Rounds following Dick's stern directive, I ended up talking for several hours not with an aspiring artist attentive to safeguarding his "instrument" but to a full-time locksmith from the Bronx who was also a part-time auxiliary cop. After several drinks Tony confided in me that he was currently letting a sixteen-year-old Puerto Rican kid -- whom he'd met in a gay bar -- stay in his apartment. He was doing it as a favor for a friend, another cop, who'd fallen for the lad but had no place to house him.

That night Tony and I exchanged phone numbers. He called the next day, came down for another three hours of talk, told me he wasn't interested in hustling me, acknowledged that he was carrying a gun, gave me a big hug at the door, expressed the hope that we could get together again later in the week, and promised -- as one might an older brother or duenna -- to call me later that night to let me know he'd "gotten back to the Bronx safely." At this late date I've lost all memory of what followed, but not much of anything, I think. What I wrote in my re-inaugurated diary that night was that I thought he was an "enticing package of nonconformities, though so muted and underplayed as to seem the essence of normality -- New York normality. My interest more cerebral than chemical. His, too, I suspect."

I didn't return for a while to Rounds, but Dick's instincts had been right: chatting up an enjoyable storm with Tony -- the hustling context irrelevant -- did help push me to going out more, to start accepting invitations that I'd been almost automatically turning down. A few of the parties were even fun. At a shindig hosted by Joe McCrindle, founder of the Transatlantic Review, for Denis Lemon, editor of the London Gay News, I ran into some old political comrades, Betty (now Achebe) Powell and Ginny Apuzzo, and we got happily high on two joints I'd brought along. I didn't care for either McCrindle or Lemon, but the novelist Bertha Harris (Lovers) was also at the party, and every time I saw her I liked her more -- tough integrity, smartass funny.

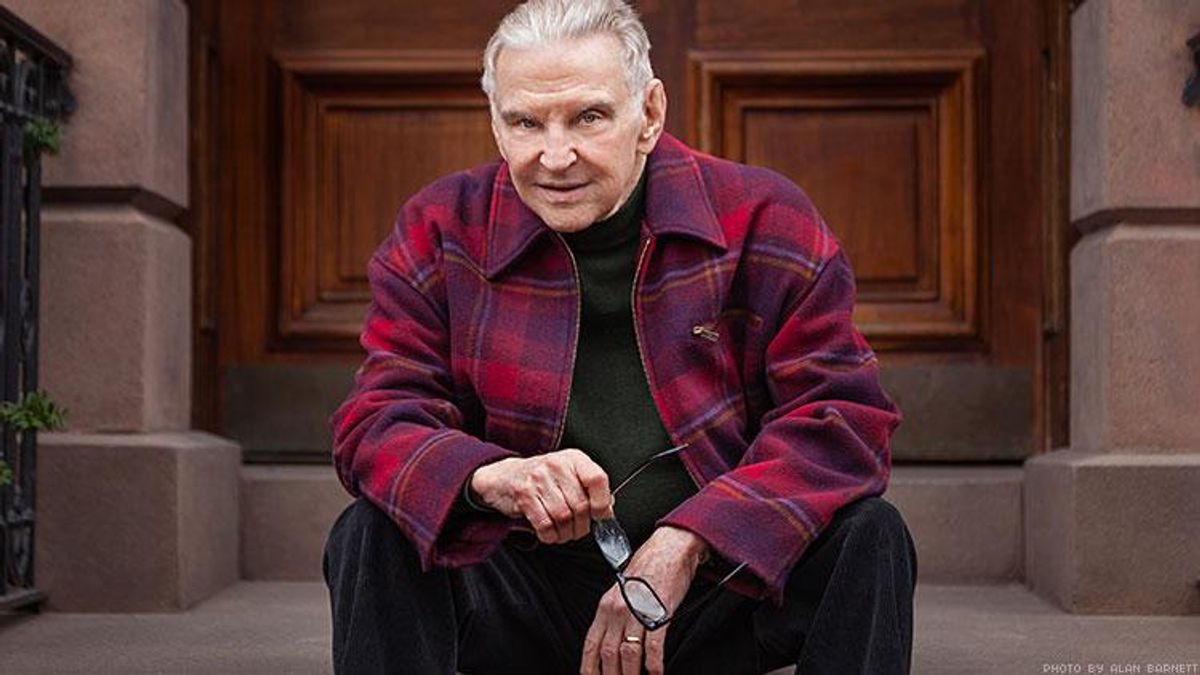

Excerpted from The Rest of It: Hustlers, Cocaine, Depression, and Then Some 1976-1988 by Martin Duberman, courtesy Duke University Press.