Books

Eddie Murphy's Blisteringly Antigay Comedy Act Scarred Guy Branum

In an excerpt from his new memoir, out comedian Guy Branum recalls the damage wrought by a stand-up special.

August 01 2018 3:02 AM EST

October 31 2024 6:14 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

In an excerpt from his new memoir, out comedian Guy Branum recalls the damage wrought by a stand-up special.

Eddie Murphy: Delirious begins with the exhortation "f****ts are not allowed to look at my ass while I am onstage." This gets an applause break. It is a joke in and of itself. What follows are four minutes of exhaustive detail about everything that is gross about gay men. He declares that he has nightmares about gay people; he does impressions of popular celebrities, imagining how ridiculous it would be if they were gay. He expresses concern that his girlfriend will "carry AIDS home with her" after a tennis date with a gay man.

I did not remember this. In my head, Eddie Murphy: Delirious was the special that made me fall in love with stand-up, that taught me the language of the art form, and stood as the paragon of what confidence in comedy can and should be. When I naively decided to rewatch Eddie Murphy: Delirious a few years ago, to let its greatness wash over me, I was stunned to discover its beginning was this unrelenting tirade against the ridiculous putrescence of the gays.

I thought back to me, lying on a carpet at nine years old, consuming this work wholly, lapping up Murphy's every word, intoxicated by the power and humor behind it. I thought about the way I had also consumed ideas that would poison my understanding of myself before I knew they were about me. I had to confront the very confusing reality that this special that was one of the building blocks of my love of stand-up, that contributed to my understanding of the language of the thing I do professionally, also taught me the building blocks of the homophobia that would keep me closeted and self-hating into my twenties. I was forced to accept that as deeply as my love of stand-up comedy was baked into me, Murphy's disgusted view of gay men was as deeply in my bones. These things cannot be extricated from each other, and I cannot wholly dismiss or reject Eddie Murphy: Delirious any more than I can wholly dismiss or reject my father. Both of them did things that scarred, abused, created, and nurtured me.

In the special, Murphy says, "I kid the homosexuals a lot, because they homosexuals." The audience laughs: f****ts deserve what they get, they seem to say. Then he says, "I fuck with everybody, I don't give a fuck." This is a common refrain among comics who don't want to be criticized. The implication is that everyone is a fair target, so everyone gets mocked equally. But do they? Does Murphy take aim at Kazakhs or Methodists or white men or people with over a 750 credit rating? Would he think to? Would he have the capacity to dehumanize these people in the cultural landscape of 1983? Can you ever reduce a white, cisgender, heterosexual man to nonexistence with the completeness that a word like "f****t" so simply, elegantly achieves?

When I was nine, I was pretty certain I was a person, and Eddie Murphy was powerfully, resoundingly telling me that f****ts weren't people. For over a decade afterward, I would solve that equation with the clear answer that I was unequal to the word "f****t." To quote the West End musical Everybody's Talking About Jamie, I built a wall in my head. It took years of experiencing my own life as a gay guy to question these terms that had been defined for me.

When I started doing stand-up comedy, I didn't realize there were no gay men who were nationally headlining comedians. I didn't think about it. I was used to living in a world without gay people, or where gay people were confined to the cultural spaces defined for them. I never noticed.

As I sat at open mics, I heard comics, mostly straight men, some straight women, using "fag" and "gay" as shorthand, defining themselves away from the danger and disgust of these characters. That's the thing: f****ts in these comics' acts were characters, cartoonish caricatures without a soul or identity outside their faggishness. I realized this bogeyman of a fag was able to persist only because it was a space where no fags were actually talking. In stand-up comedy, fags were constantly discussed but never discussing. It became my obsession; my only desire, to get up onstage after one of those perfunctory, half-hearted open-mic fag bashings so I could talk back.

There's a Margaret Atwood poem in which she describes her daughter playing with plastic letters, "learning how to spell / how to make spells." She talks about women of the past who ignored domestic life to "mainline words," and punctuates it with "A word after a word after a word is power."

There are not currently A-list out-of-the-closet gay male stand-up comedians. This is an absence, and it is more. Stand-up comedy is laid thick with spells, spells about f****ts and women and Asians and Muslims and airplane food. They are spells that define people as subjects and objects, heroes and monsters, and we cannot, in a field in which the spellcasters are overwhelmingly male and straight, behave as though these spells bind everyone equally or similarly. "I make fun of everyone" doesn't exonerate anyone, because the issue in the sentence isn't the object; it's not "I make fun of homosexuals" or "I make fun of everyone." The issue is the subject. Who gets to be "I"?

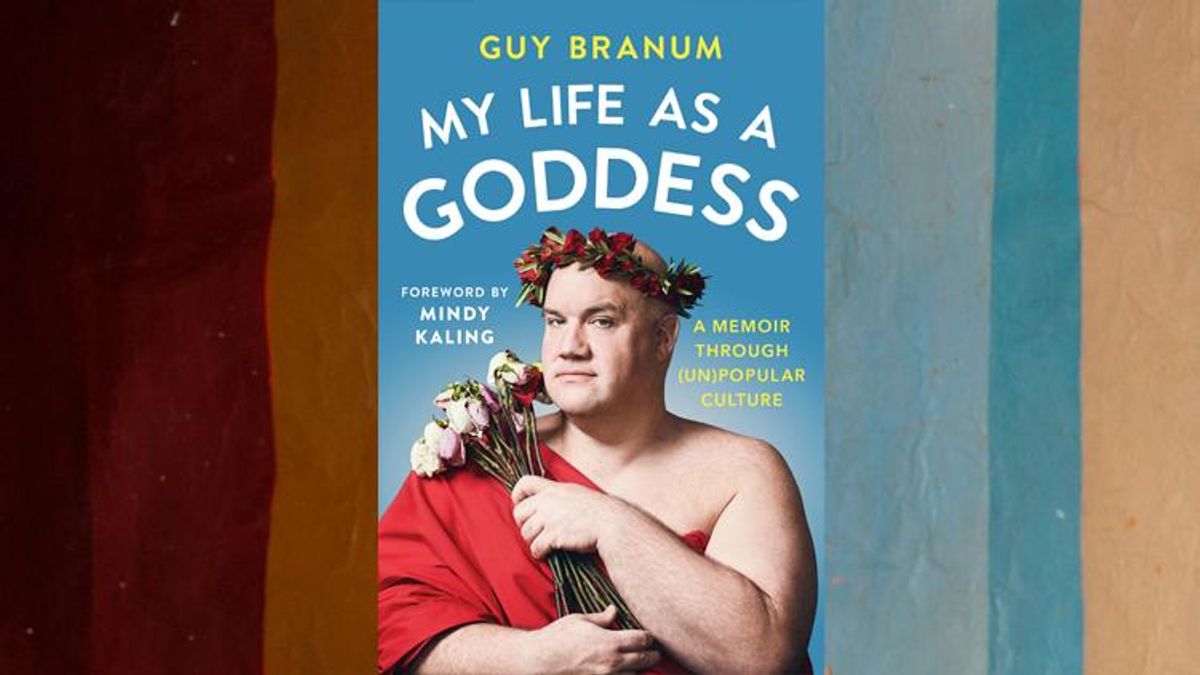

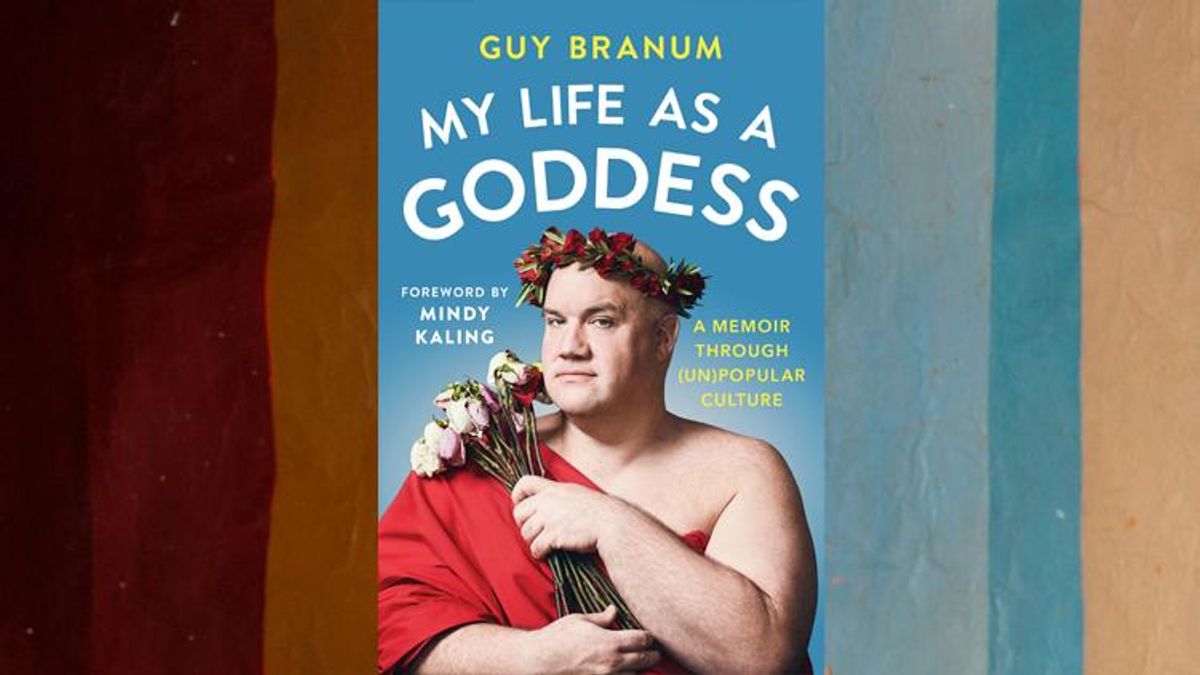

Excerpted from My Life as a Goddess: A Memoir Through (Un)Popular Culture, courtesy of Atria Books.