Picture it: New York City, 1983. It was the dawn of the HIV epidemic in America, when love and loss were practically synonymous for those in the queer community. As the plague raged, killing tens of thousands of gay men in a matter of years, our government did virtually nothing to stop it. It was a time of lawlessness, a time of integration, and a time to revolt.

Richie Jackson, then 17, had just started attending New York University, where he discovered there was a queer community. As the celebrated TV and theater producer (Nurse Jackie, Torch Song) notes in his new book Gay Like Me: A Father Writes to His Gay Son, "It was as if I'd joined a secret society, bound together by oppression, and we reveled in our clandestinity even as we fought to assimilate."

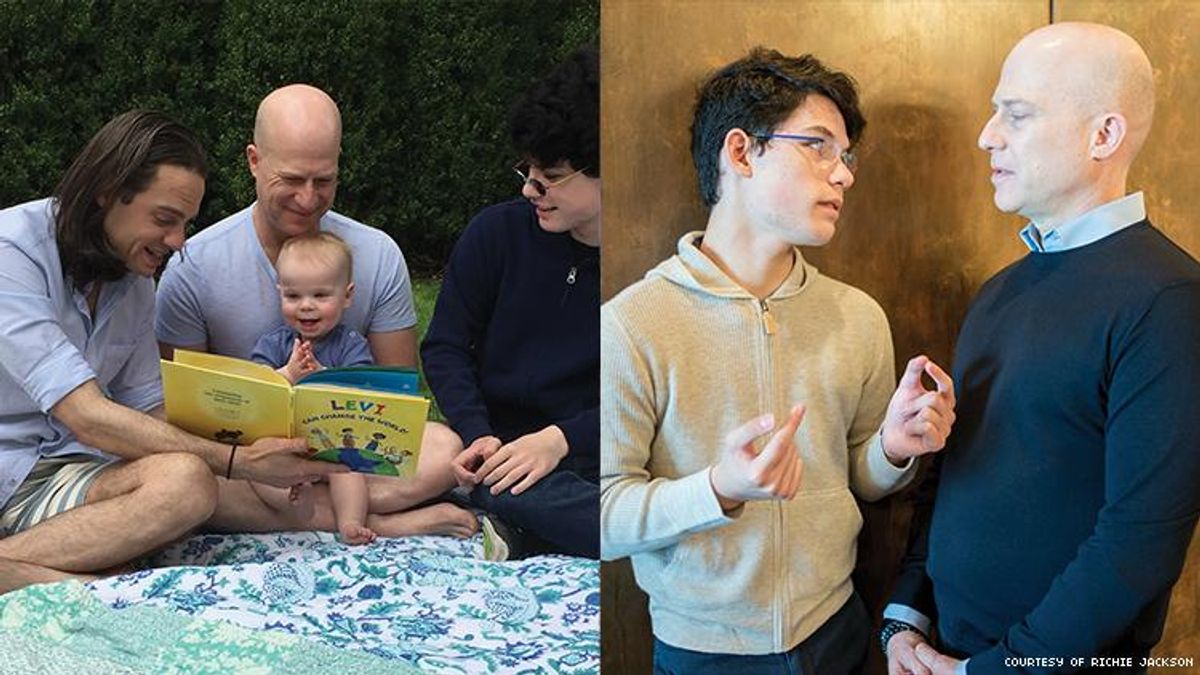

Thirty-six years later, his 18-year-old gay son, Jackson Foo Wong, is following in his dad's footsteps at NYU. But Wong's experience as a gay man in America is vastly different in 2019.

For starters, HIV is now a chronic manageable condition and the advent of PrEP (and U=U) has changed the landscape of safer sex practices. Marriage equality is no longer a fantasy, but the reality. LGBTQ visibility is part of most American's daily lives thanks to wider representation in television, film, and politics. And social media has united those previously isolated, reminding us that we are never alone.

When Wong (whose biological father is Jackson's ex, actor B.D. Wong) came out at 15, Jackson and his husband since 2012, theater impresario Jordan Roth, were naturally accepting. But a generational divide exposed itself when Wong retorted that being gay is "not a big deal" nowadays.

It was a sentiment that inspired Jackson to write Gay Like Me to Wong -- and other young queers -- explaining, educating, and sometimes warning him not to get complacent.

He writes, "It is critical that I tell you everything I know -- of everything that I have learned, of every rise and of every depression, of so much that I have kept to myself so that you would feel safe. All of that I have to tell you now."

The language is paternal and nurturing, and dives deep into Jackson's own experiences and the lessons he gleaned about relationships, sex, love, friendships, and resistance against the backdrops of the AIDS crisis, "don't ask, don't tell," marriage equality, gay parenting, and the era of Donald Trump.

While his son was the inspiration, Jackson's intention is farther reaching. In many ways, Gay Like Me is a manual for all LGBTQ youth coming of age with minimal access to queer history or those whose circumstances prevent them from gaining knowledge directly from LGBTQ elders.

"Think about this: for centuries we have been stigmatized by religion," Jackson explains to The Advocate. "We have fought back battle after battle with our government. We've survived the plague. We disappoint our parents. We survive bullying from our childhood friends. And all of that lines up against us, not because we are a defect, [and] not because we are worthless. The government and those religions, they all know our power is our gayness. That's what they're trying to stop."

Jackson recalls a grade school gym teacher who learned he'd joined the chorus and "told all the other kids to 'jump on the f****t.' And they did. I literally couldn't understand. I knew what that word meant and I knew he identified it in me. He saw it, and I couldn't understand why it was a negative."

Although the taunting and bullying followed Jackson well into junior high, he says his queerness wasn't a prison but a refuge.

"I am the most alive when I am reveling in my gayness," he says. "Every gay person has to keep a double vision of themselves: how America sees them, but they [also] have to keep secure so that America's negativity doesn't seep into their beautiful, clear vision of their gayness. That is what makes them special. And you have to hold both."

Earlier this year, Jackson combated writer Andrew Sullivan's contention in New York magazine that LGBTQ people should get "on with our lives, without sexual orientation getting in the way."

While being interviewed at the Atlantic Festival, Jackson retorted, "It cannot be that we have fought back centuries...all just to get our liberation so that we can say being gay isn't a big deal.... I don't want to celebrate being gay just one day at the end of June every year. I want to be able, every day, to say this is why I am as successful as I am, why I have a beautiful family."

Jackson wants to share that message with younger LGBTQ people and to learn from them in return.

"Part of the reason I wrote Gay Like Me is because of the generational divide," he continues. "Guys my age don't recognize the community we were born into. I do think speaking to each other, sharing what the older generation went through and know and learned is useful. And then, we have a lot to learn from young people. My son is the one who helped me understand the positiveness of the word 'queer,' which I really struggle with."

Strong, determined, and intentional, Jackson doesn't hide the fact that he's ready to go toe-to-toe with conservative groups like One Million Moms, whose mission it is to convince the country that LGBTQ families negatively impact children.

"I have been through a plague, so One Million Moms don't scare me," he says. "Here's what I know about gay parents, about LGBTQ parents: You have to be deliberate about it. It doesn't just happen that you have a family. It takes enormous work and a lot of hurdles.... So I promise you, the gay parents who do exist, they are full of purpose and love and potential."