I meet Dr. Wilson in the early evening as we always do, after her official office hours. It's the middle of fall so the sun has already set. She knows the NFL guys need discretion, so we don't meet at her office, but at some school for kids with disabilities, a quiet spot where she has access to some space. When I pull up in my truck, she is there in her car, waiting for me.

Damn.

I haven't snorted a thing in almost an hour.

I gotta down this Vicodin.

"I started to wonder if I'd missed another cancellation," she says.

I kind of enjoy the little bit of snark out of her. She's earned it.

We go inside and I walk straight for the bathroom where I can snort the stuff.

I can't lose the high right now.

When I finally walk into our meeting room, she is sitting there thumbing through some notes. I figure she's annoyed with me after all the cancellations, now making her wait for me once again. She couldn't be more professional.

"How have you been since we last talked?" she asks.

I sit down across the long boardroom table from her.

"You know, same."

She pauses, looking at me, studying me. I am spacing the fuck out, can't stay focused on her. My eyes are everywhere.

Fuck, did I overdo the pills? She knows. She has to know.

"Tell me about your day . . ."

Fuck this.

"Okay, I need to tell you something," I say.

She sits back, her eyes laser-focused on mine, like she is some Jedi working one of her mind tricks.

I stir in my seat. I can barely sit up straight; the drugs are shooting through my veins, electro-charging my whole body.

Stop fucking dragging this out.

"I gotta tell you something I've never told anyone," I say. "And you can't tell anybody, right?" That is my biggest paranoia, that she will tell someone at the Chiefs and all hell will break loose.

"As I've said, I cannot legally discuss anything we talk about," she responds.

"Not even the team?"

"Not even the team," she assures me. Then leaning in, gravely: "But if I believe your life is in imminent danger, I am obligated to intercede." She knows my life is on the line. She knows.

I have cried by myself so many times, so many nights. All of it is bubbling to the surface now. Even with the drugs pulsing through me, I can't suppress it. Tears spill down my face. This big behemoth of a man crying in front of this woman. I feel embarrassed, but I can't stop it. Every time I open my mouth, I am consumed with thoughts about all I have been through. The drugs. The guns. Pretending to date women. Lying. Practicing lying. It's probably a good thing I'm high, because there's no chance I would say anything more if I were sober.

"Dr. Wilson . . ." I focus really hard, staring at the table. The blank table. No distractions.

Say what you gotta say.

". . . I . . ."

She sits there patiently, not saying a word, that fucking silent game again, waiting and waiting like she has so many times before. Silence but for the buzzing of the fluorescent lights and my quivering body.

Just fucking say it.

"I'm . . ."

Say it, you f****t!

Deep breath.

"I'm gay."

I feel like I'm hyperventilating, struggling to breathe. I've never said those words aloud to anyone. Not even myself. I cover my face with my hands, hoping to crawl into a hole and die. Tears are streaming out of my eyes now. I am at the same time relieved to finally share my truth, and ashamed of the words even as I say them.

What the hell did you just do, you fucking idiot?

Dr. Wilson doesn't say a thing at first. She just sits there, watching me blubber like a fucking f****t. Then: "That took a lot of courage, Ryan."

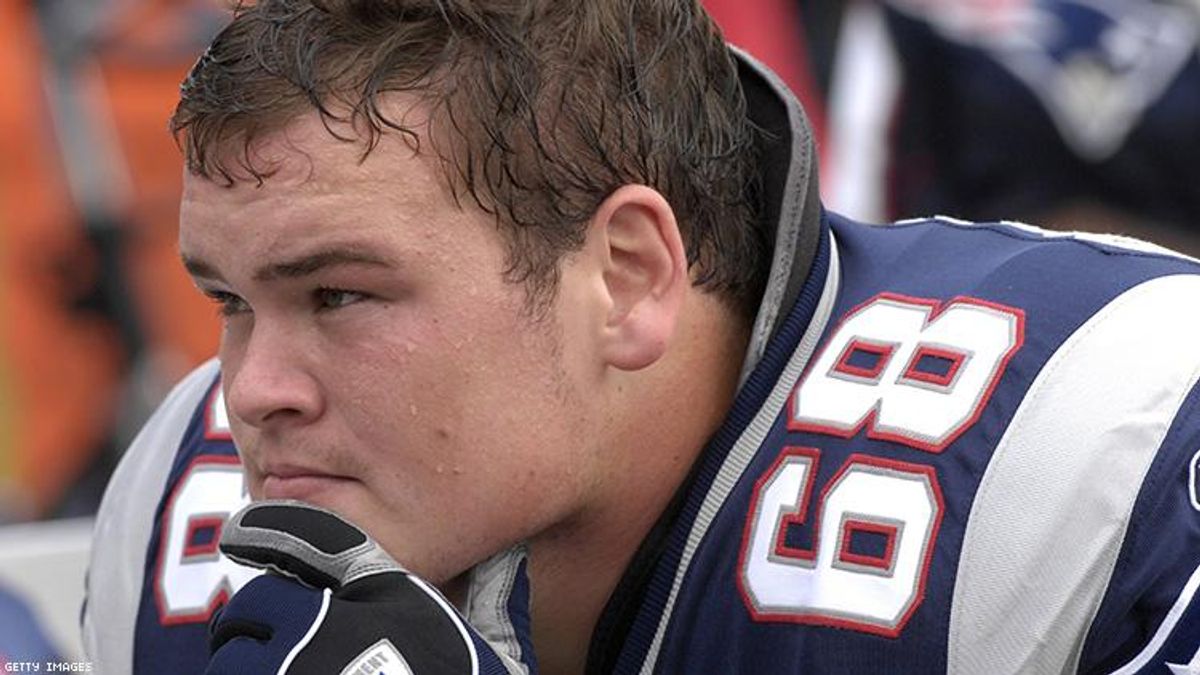

I look up at her, this sheepish expression on her face. She gets out of her seat, walks around the table, and wraps her arms around me. All my life I have told myself that people will hate me if they know the real Ryan O'Callaghan. I'd have to kill myself if they knew. This woman, a stranger just a couple of months prior, hugs me. She's supposed to hate me, but she hugs me. It takes a lot more strength to be honest with myself, about myself, than it does to lie. It took awhile to build up that strength to tell Dr. Wilson. In that little classroom that evening, she meets that strength with strength.

"I want you to know," she says as she walks back to her seat, "that you're not the first NFL player to sit in that chair and tell me that very thing."

The tears are slowing now. I pull my hands away and look up at her.

"You're not alone," she says.

To know I'm not the only one isn't a shock. I had already heard Esera Tuaolo talk to us at our Rookie Symposium years earlier. Still, hearing that she has counseled another gay player, maybe not so long before I sat in that chair, gives me a glimmer of hope, like this particular woman has been sent to me by some greater power. And I don't even believe in that hocus-pocus shit.

After that the floodgates open. I tell her about the cabin and all the guns. I tell her about the drugs. She already knows about some of the painkillers, but this time I tell her everything. And I tell her about the suicide note, just waiting for the wrong moment.

But telling some stranger I'm gay doesn't suddenly change the outlook I have embraced since I was a kid. The life of a gay man is still not worth living, the people closest to me will still hate me for it, and I am still going to have to end it all.

"Why?" she asks. "Why do you assume you have to kill yourself?"

I start telling her about being a kid in Redding. The isolation of those family picnics. The constant jokes I heard from the men in my family about being gay. The shit guys said in the Enterprise High School locker room all day, every day. Forget about the messages in the media or the lack of role models. The people closest to me told me constantly, from my first memories, that I was straight and gay people were bad. I share with Dr. Wilson that all of this has translated in my head into gay people deserve to die. Whether or not that's what they said, that's certainly what I heard.

"That was a long time ago," Dr. Wilson says. "How do you know your parents will reject you, their son, today?"

In so many ways, adults and their parents fail to know each other, clinging to a past that they all left long ago, but that they assume the others still live in. When I go home to visit, my mom makes me meals I loved as a kid. Yet my tastes have changed. I love her for making my "favorites," yet she doesn't really know what my favorites are anymore. But my mind isn't ready to believe they have changed their thoughts about gay people, even if twenty years have passed.

"I just know," I reply.

"So you're just going to end it all without ever testing your game plan?"

She's good. If you make it all the way to the NFL, you know a thing or two about developing game plans, the importance of running them by people and testing them at practice. She knows that one way to get through to a guy like me is to appeal to the sense of reason instilled in me from a decade of organized football at the highest levels. She convinces me that adjusting my game plan makes a lot more sense. Why not go home, tell my terrible secret to my parents, and then if they have the reaction I expect from them, at least I will know before I put a bullet through the barrel of one of those guns.

When I get back into my truck that night, the tears become a river right there in the parking lot. Telling Dr. Wilson my secret fills me with just about every emotion I have ever felt before or since. Anger. Worry. Fear. Hope. All my life I have been living with my own personal thoughts about being gay. Just telling her feels like a million pounds off my shoulders. This is the very first time I have ever been totally honest with someone about myself. And it has only taken twenty-eight years.

Twenty-eight fucking years.

More than just being two ears to hear me, Dr. Wilson is helping me see that maybe, just maybe, all of that stuff my dad and my uncles and so many people around me have said about gay people might not be how they actually feel. She helps me see that if I am suddenly the gay person they are talking about, they might change their tune. For the first time in my life, it seems possible that all those jokes in the park as a kid weren't actually about me at all.

Excerpted from My Life on the Line: How the NFL Damn Near Killed Me, and Ended Up Saving My Life by Ryan O'Callaghan and Cyd Zeigler, courtesy of Akashic Books.

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4