Books

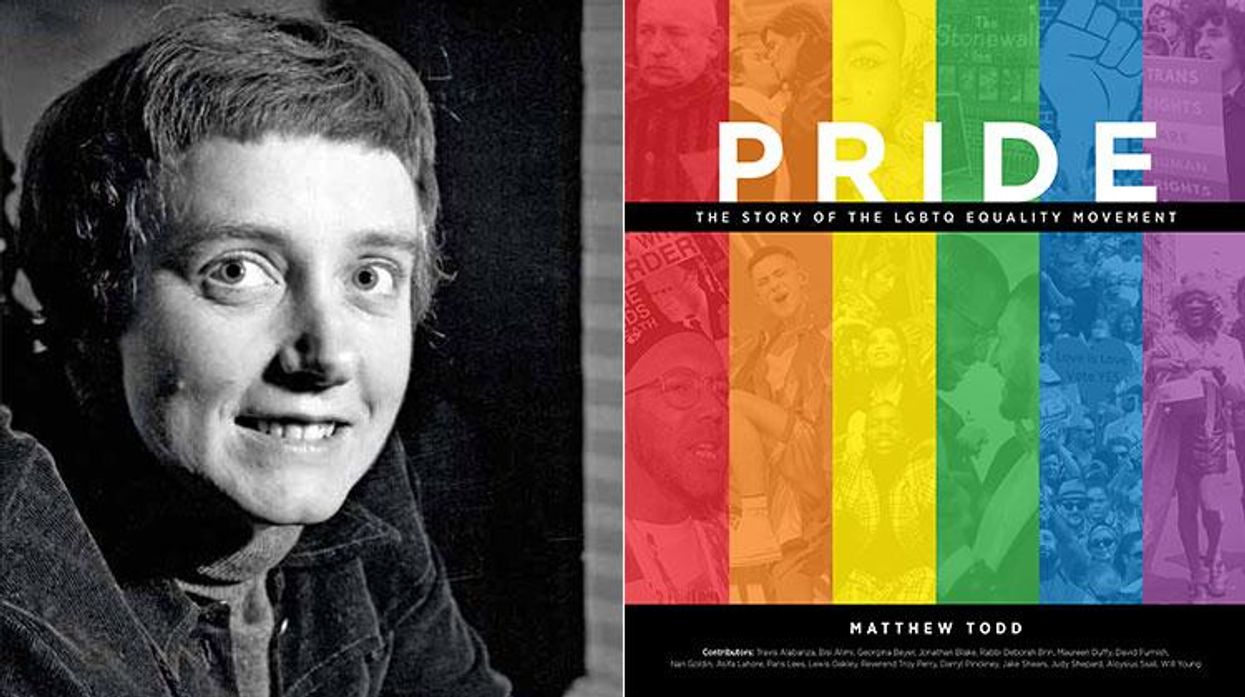

Maureen Duffy on Becoming Britain's First Out Woman in Public Life

The 86-year-old writer of The Microcosm recounts the early days of LGBTQ+ activism in the United Kingdom.

June 23 2020 10:57 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

The 86-year-old writer of The Microcosm recounts the early days of LGBTQ+ activism in the United Kingdom.

The following essay by English gay rights activist and novelist Maureen Duffy is from Pride: The Story of the LGBTQ Equality Movement, a new book by Matthew Todd, the former editor of Attitude magazine. Excerpted with permission from Weldon Owen.

When I first came out to myself in the early 1960s, both gay men and gay women were very much in the closet. There were notable gay male pubs in Earl's Court and Soho, and dotted throughout the capital, but social venues for gay women were much less common knowledge. A series of gay trials of well-known figures, principally of Sir John Gielgud in 1953, had culminated in the setting up of the Wolfenden Committee to look into the whole question of male homosexuality along with seemingly related matters.

So uptight was the closet, due in part to a respectable working class mantra that "you don't talk about such things," that a closely knit group of us of both genders went through the three years of university together without ever knowing that any of the others were gay.

So when I came out to myself, in the belief, held by most British people, that the French were better at sex, or at least more open about it, I turned to Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex for enlightenment - and I wasn't disappointed. After reading what she had to say, I thought, "Well, that's alright then." But there was still the question of what to do and where to go to find others.

Fortunately my then "partner," to use a contemporary word, knew a gay vicar who invited us to join him and his "boyfriend" at a pub on the Embankment, where we might find someone who knew where the girls went. And that was how I found myself in the Gateways in Chelsea, dancing to the jukebox until closing time. Leaving there could be tricky. Sometimes there would be a group of men waiting outside to shout abuse or even spit at us. Cries of "Come on over here, darlin', and I'll show you what it's all about," although seemingly good-natured, could be threatening.

Meanwhile the campaign for the decriminalization of male homosexuality was in full spate. The Wolfenden Committee had reported favourably in 1957. Not only did I strongly believe that the prosecution of male homosexuals was wrong but also that homosexuality was, and always had been, a facet of human nature. But I was also becoming increasingly aware that although the clamour for the law to change for men was growing louder in all forms of the media, including voices against it giving it an even greater boost, the fact that there were also gay women receded further into the background - as just the left-behinds who couldn't get a man. Finally I decided that I would write a companion book to D.J.West's Homosexuality, talking about the jobs we did, and our lives, in an attempt at equality. The very word "homosexuality" was misinterpreted as being derived from the Latin word "homo," meaning "man," rather than the Greek word meaning "same."

Accordingly I interviewed a selection of gay women with my clunky tape recorder and drew up a synopsis. I gave this to my agent, who arranged a meeting with the publisher Anthony Blond, known to publish some titles thought risque, such as The New London Spy: An Intimate Guide to the City's Pleasures.

However, Blond's view was, "As you don't have a sociology qualification no one will let you do it. Why don't you write a novel instead?" I turned this over on the way home, rang my agent and told him that was what I was going to do. And so I began The Microcosm, banned by the Vatican, put on the Index and banned in Ireland, then banned in South Africa because it showed Black and white characters socializing together. But I was also written to by dozens of women thanking me and saying, "I thought I was the only one in the world."

As a result of the publication of that novel I became very much involved in the male campaign - the TV clip of an interview I gave can still be found on the BBC archive.

Wolfenden succeeded in 1967, but even so Gay News was prosecuted in 1977 for blasphemous libel with its James Kirkup poem centred on the crucifixion. In reply I published "The Ballad of the Blasphemy Trial" and waited for the skies to fall. But nothing happened. However, the secretary of the National Secular Society was also prosecuted for sending copies of the Kirkup poem through the post. Brigid Brophy and I attended his trial to show our support for him.

Gradually things have opened up in the U.K., first with recognized civil partnerships, then same-sex marriage - except in Northern Ireland. But still LGBTQ people in many parts of the world are persecuted, and even tortured and killed.

When I first came out to myself, it was into a completely buttoned-up society where to be gay was stigmatized or at best jeered at. The temptation for many, both women and men, was to hide their terrible or humiliating secret which set us apart from "normal" society and its norms. The wealthy women of Britain and America, Gertrude Stein, Radclyffe Hall and many others, holed up in Paris between the wars. For those of us who didn't have that option, we had either to live in secret or like me be bloody-minded and brazen it out. So it was I found myself in battle again against Maggie Thatcher's Clause 28 in the 1980s. Then came the AIDS epidemic and I was writing poems to be read at the funerals of three of my friends. We have come a long way, but we must never forget the clock can always be put back.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes