'Last Call Chicago' Reveals the Rich History of Queer Bar Culture

09/30/22

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

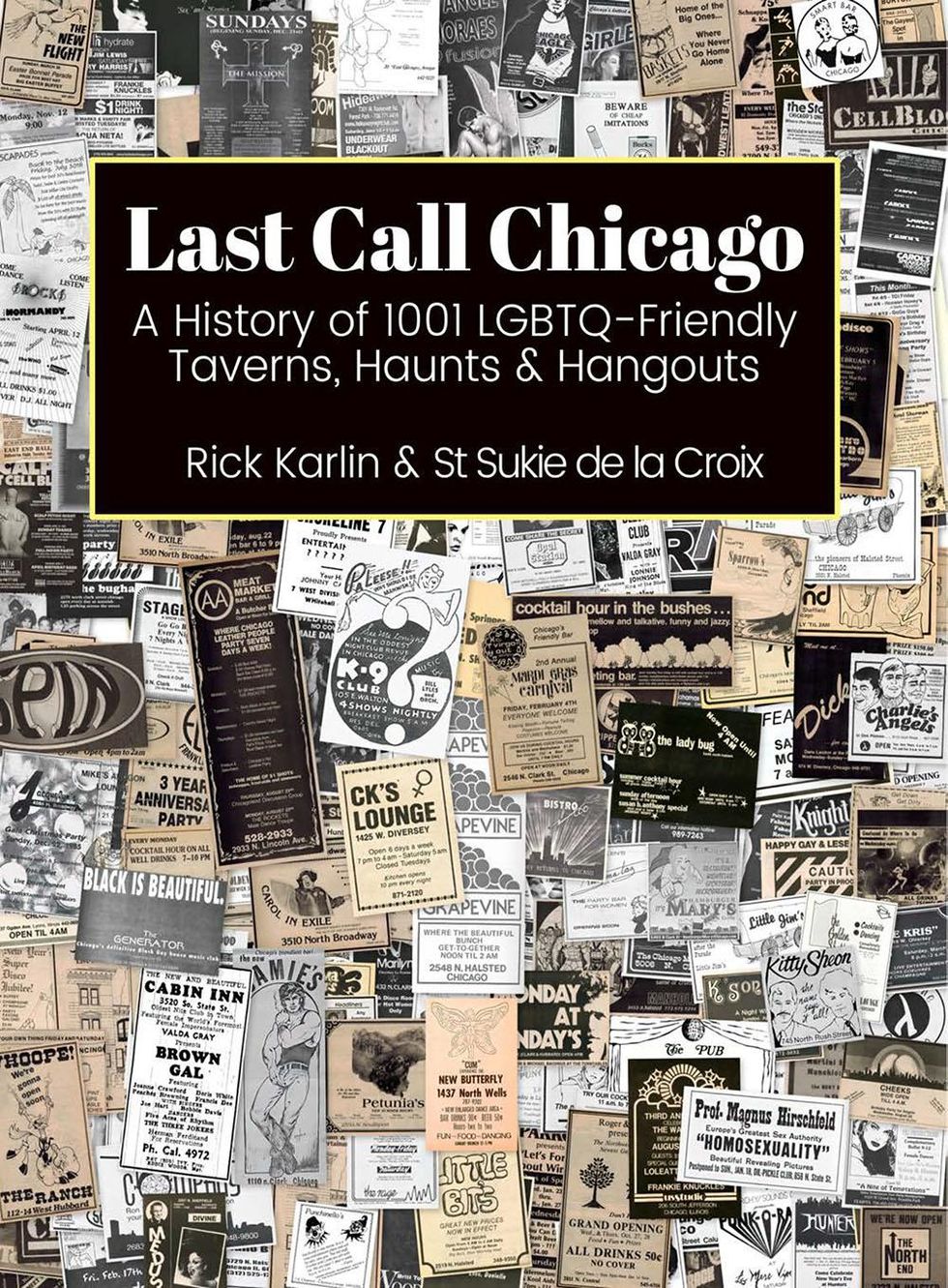

Members and allies of Chicago's LGBTQ+ community have an invaluable resource in Last Call Chicago: A History of 1001 LGBTQ-Friendly Taverns, Haunts & Hangouts, a book by journalists Rick Karlin and St Sukie de la Croix.

The book is "a history of LGBTQ venues in Chicago going back in time as far as records of such venues exist," according to publisher Rattling Good Yarns Press. Along with vintage advertisements and detailed records of where the bars were located and when they were in operation, it documents personal stories from the people who found refuge and community with these businesses, many of whom died decades ago.

"So much of our life is in the bars, and that's where so much gay history took place," Karlin told The Advocate. "Before there were organizations, any kind of planning took place in the bars. So it's really important to document that history. It's really our hope that this will encourage people to do the same for their cities, because I think it's a really important document to have."

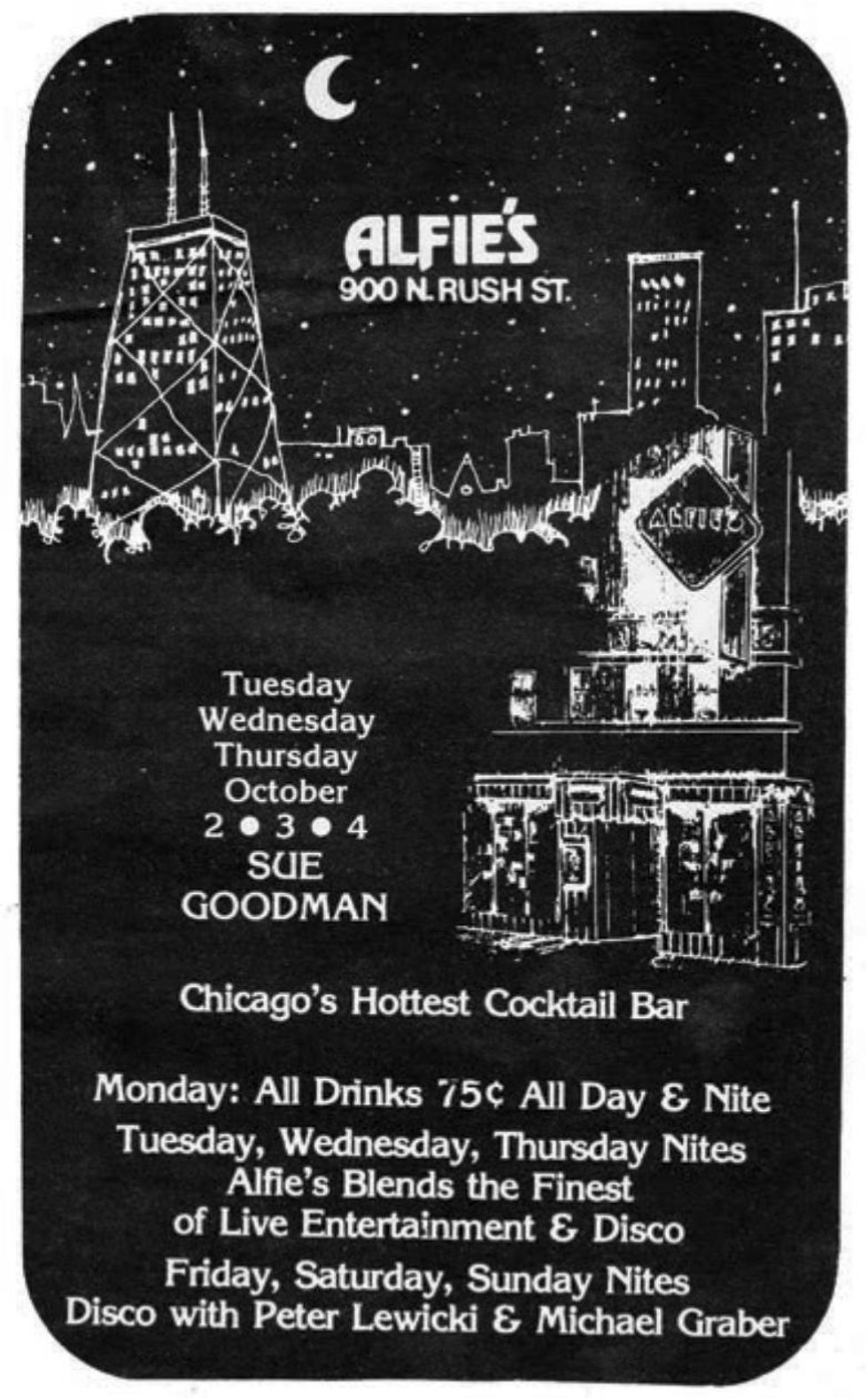

Alfie's, circa 1976-1980. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 7

Karlin got the idea for the book while reminiscing with friends about the gay bars in Chicago. He'd been the entertainment editor at various publications for 25 years, so he had a lot of knowledge about the local bar scene. "I can't remember my niece's birthday," he joked, "but I can remember that the bar on Elston Avenue was called Scooters."

To flesh out those stories, Karlin knew he needed to collaborate with another journalist on the project. For years, de la Croix wrote a column in the gay papers called Chicago Whispers, which later became a book of the same name, where he'd interview people about bars from as far back as the Prohibition era of the 1920s and '30s. "The original idea for [Last Call Chicago] may only be four years old, but Sukie, without knowing it, has been doing the research for it for 20 years."

"I'd interviewed about 500 people, just about their lives in Chicago," de la Croix said. "The bars cropped up a lot, because the bars back then were the community centers. There was no gay Catholic group, none of that stuff. Before Stonewall, that didn't exist.

"I did think about doing this years ago, but I thought, No, this is too much for one person. So when Rick called me, I thought maybe we could do that, but I didn't just want to do a list. I wanted it to be more than that."

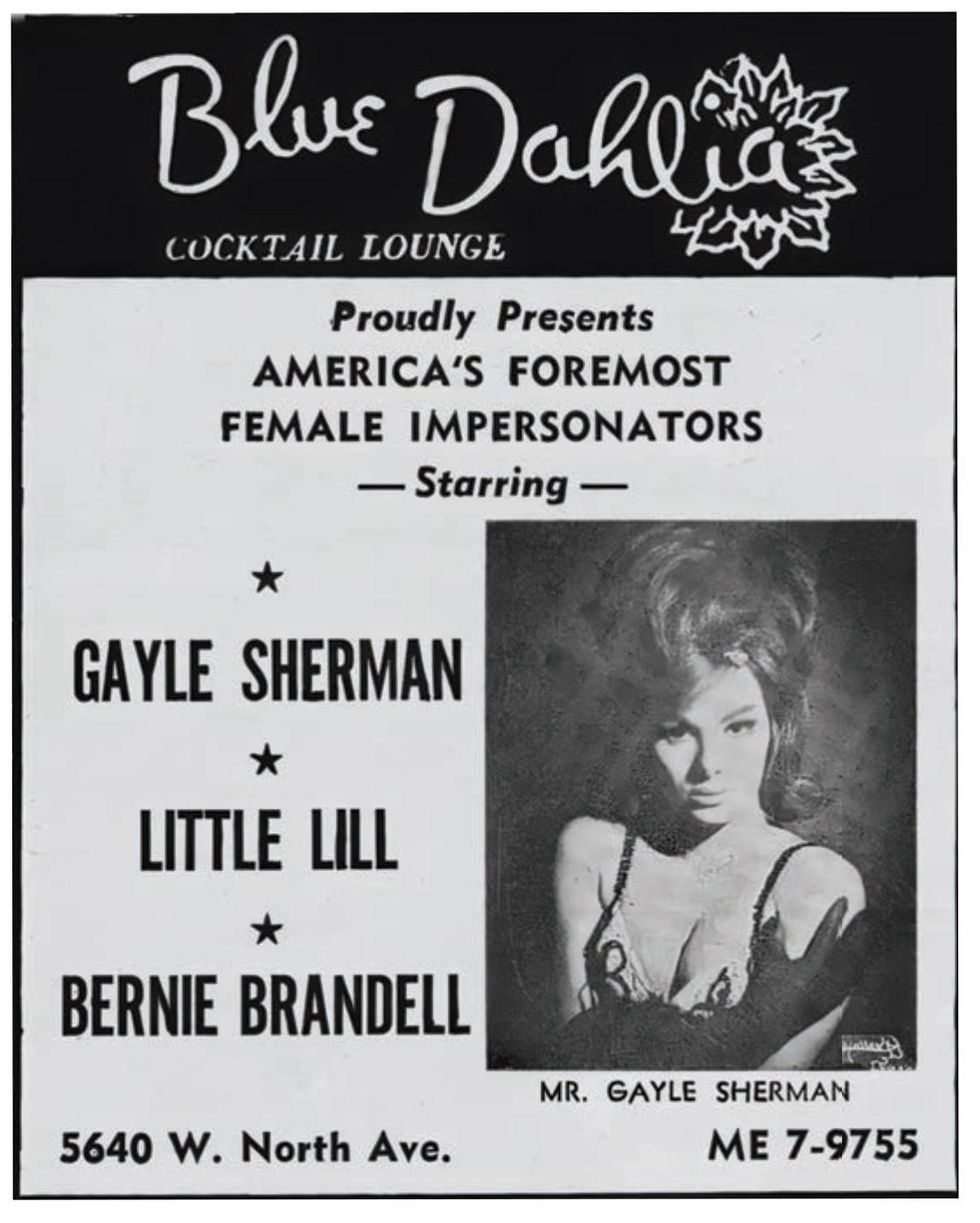

Blue Dahlia, circa 1955-1979. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 24

A lot of the book's charm comes from funny stories from bar owners and regular customers, written in the style of Karlin's gossip columns going back to 1978, where he kept readers up-to-date on the local drag queens and performers.

"We had a person who would go around to the bars and write things, and he'd bring in a bunch of crumpled-up bar napkins, and I had to decipher what it was," he said. "Normally there wasn't really enough there to make a whole column, so what I would do is take the information the bars were advertising, and I'd make some funny way to make it into kind of a gossipy thing. If you're really broke, head over to Berlin on Thursday night, where they have 75-cent drinks and a dollar cover. Helen Highwater was seen there opening her purse for the first time. I'd make up these characters and I'd write about them."

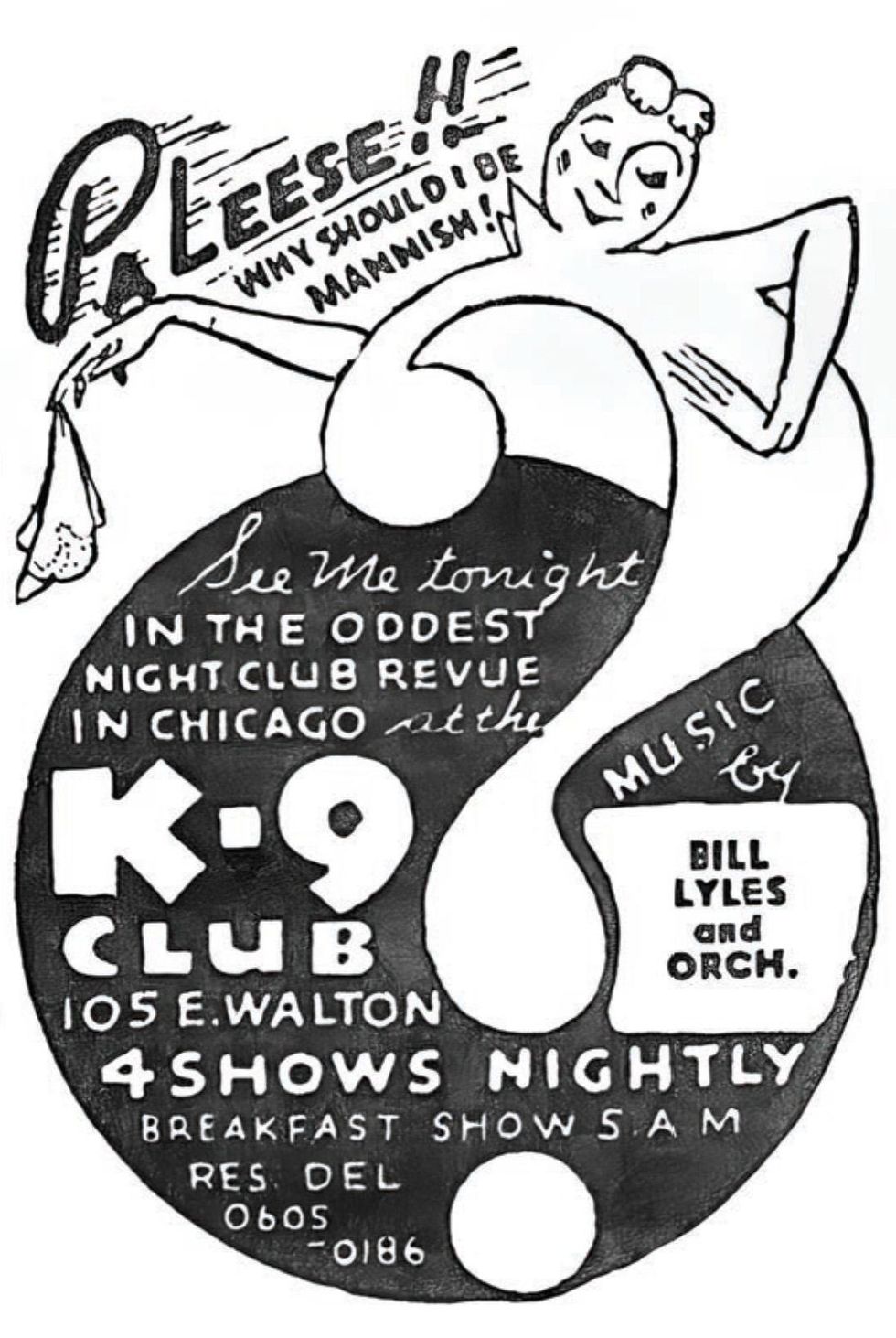

K9 Club, circa 1920s-1934. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 111

To cover the pre-Stonewall establishments, de la Croix had to do some digging through the archives. "I interviewed a man in his 90s, and he died the week after I interviewed him," he said. "He told me that he snuck into a speakeasy during Prohibition and saw a drag show. He remembered the name of it, but he couldn't remember the address, and of course it was a speakeasy, so I couldn't look in the phone book."

Before he could write the story as a journalist, he had to prove that this speakeasy, the K9 Club, actually existed. "When Prohibition ended, the next day all these clubs opened overnight. I found this old writer [who] wrote books about anarchism in Chicago, and I said, 'What was the scuzziest newspaper in 1933?'"

Sure enough, he searched the paper and found old advertisements for the bar. "It did open, this drag club. It was a speakeasy, and it did advertise in the paper. Of course, when [Mayor Edward J. Kelly] came along and found out about it, he closed it down."

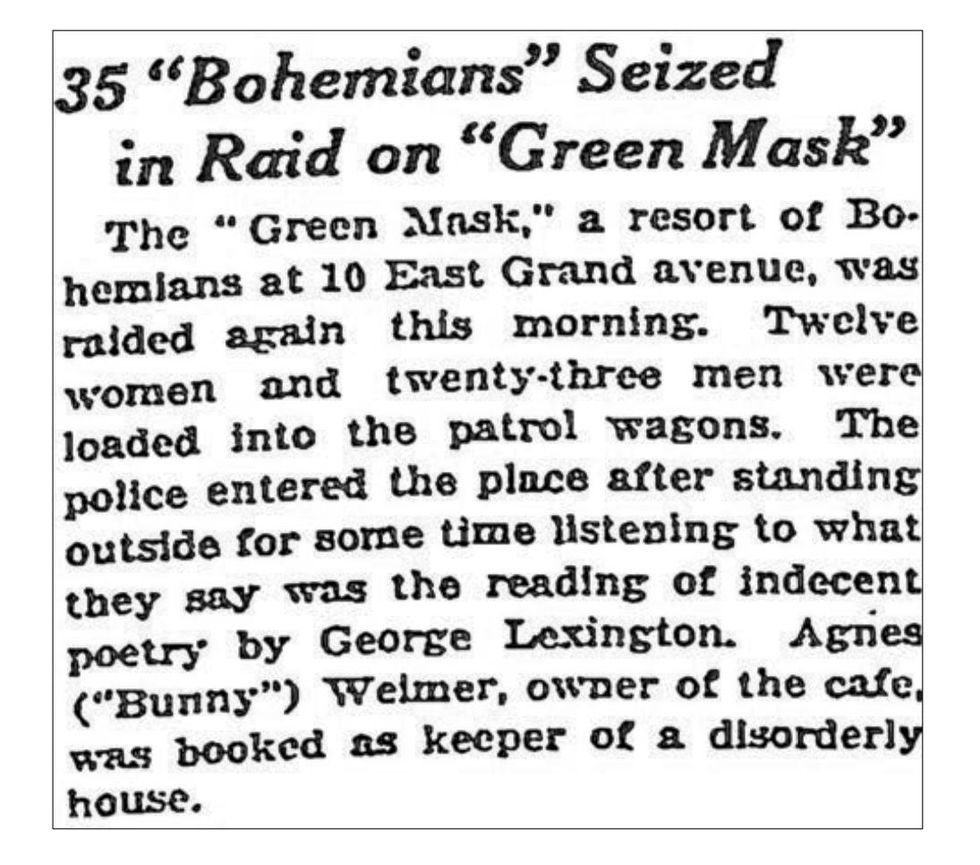

Green Mask Tearoom, circa 1920s. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 89

Many of the Prohibition-era businesses were documented because newspapers would cover police raids and arrests for public indecency. One was called the Green Mask Tearoom, located in the basement of a brothel. It was owned by chorus girl and burlesque performer Agnes "Bunny" Weiner and her lover Beryl Boughton, a silent movie actress.

Beryl "was in a cowboy movie," de la Croix said, "and she had to be in a sandstorm and it took a lot of her face off. She sued and won a lot of money, and they opened this lesbian cafe. I'd heard of this place, but I couldn't prove it until I looked back in the newspapers and found that they'd been raided many times."

At another lesbian bar called the Volli-Bal, located next to the site of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929, women had to think fast to avoid being arrested. "In Chicago right up until 1973, the law was that women had to wear three items of female apparel. When the cops were coming, they would all run into the bathroom, bar the door and swap clothes. [Butch lesbians] all had to swap with their femmes. When they opened the door it was a sight to behold, because everybody was wearing all these ill-fitting clothes, shoes that didn't fit."

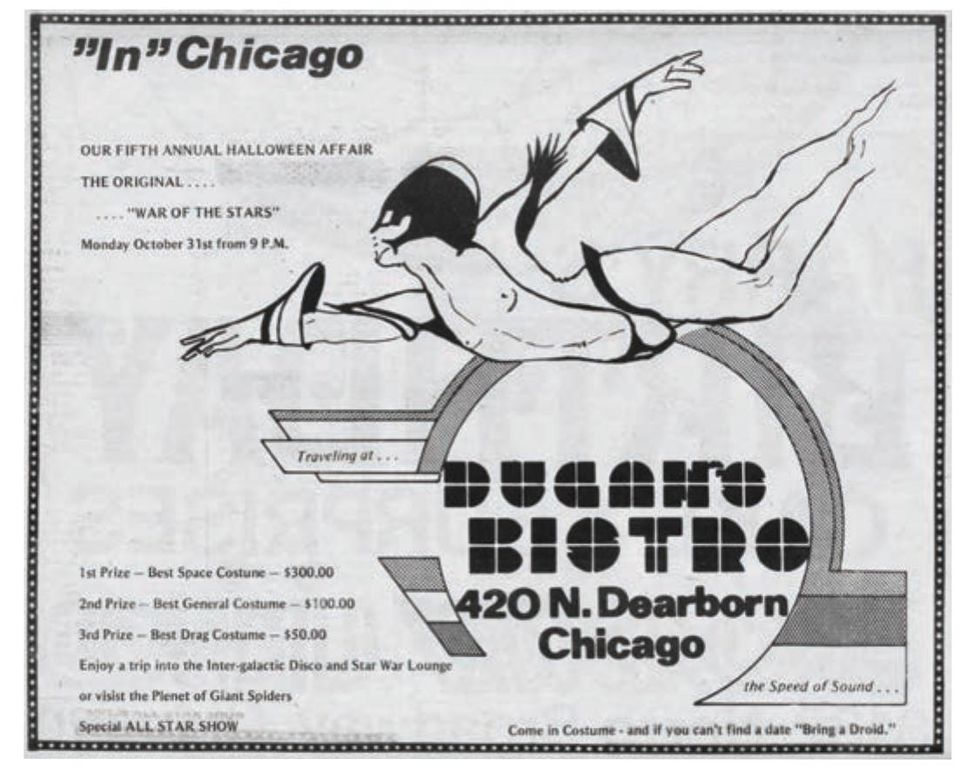

Dugan's Bistro circa 1973-1982. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 21

"I never interviewed any of the famous people, I honestly wasn't interested," said de la Croix. "I wanted just regular people. I remember I interviewed this woman, an African-American woman, and I had the tape recorder on and she told me about her life on the South Side of Chicago. At the end, I turned the cassette recorder off and said, 'Is there anything I should have asked that I didn't ask?' She said, 'Well, I was a member of the Black Panthers...'

"Maybe we all do it -- we lead our lives, and nothing seems spectacular. But I discovered during this that everybody's life is fascinating, and they don't think it is.

"I know somebody who I interviewed who performed oral sex on a mob leader. He's dead, I'll name him: Tony Accardo the mob leader. Somebody said they blew him in the back of a cab. But you don't know what's true, unless two people confirm it or it was in the newspapers."

Hamburger Mary's/Mary's Attic, circa 2005-2020. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 91

One of the reasons Chicago has such a unique LGBTQ+ history is that the city's bar culture is different from places like Los Angeles or New York. "When I was growing up here, it was not unusual for every block to have a bar on it," Karlin said. "It was a very blue-collar, beer-centric town. I grew up thinking [brewing company] Schlitz was somebody's name that lived in Chicago, because all of these buildings [where] Schlitz built the facades with their logo on it."

Until recently, a quirk of the city's liquor laws meant that licenses were connected to an address, rather than the owner of the bar. "If you had a liquor license and you wanted to move your business three doors away, you couldn't do that -- but you could let your liquor license be used by somebody else in your space. So what happened is when people got tired of running their business or they ran out of money or whatever, they just let somebody else open a bar in their same address."

Near the end of the book is a section called "Shared Spaces," listing addresses that were home to several gay bars and clubs over the years.

AA Meat Market, circa 1989-1994. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 5

"Illinois was the first state to decriminalize homosexuality, in 1961," de la Croix said. "All the obvious homosexuals in the Midwest living in small towns, drag queens and things, they all thought, This is great, so they all moved to Chicago. They moved from Indianapolis, from all over the Midwest.

"The other thing I think that helped is a weird thing to say, but the Mafia owned all the bars, and the cops took money from them. That corruption actually gave gay people a space in Chicago. So we could go to the bars and it was probably safer than other places, because the mob and the cops were actually keeping the bars going."

"Even when the cops would raid the bars, the bars would know ahead of time," Karlin added. "They would phone first to say they were raiding the bar, so they would get people out. My father was a Chicago cop, and we found out that he was one of the cops that was not only raiding the bars but on the take from the bars."

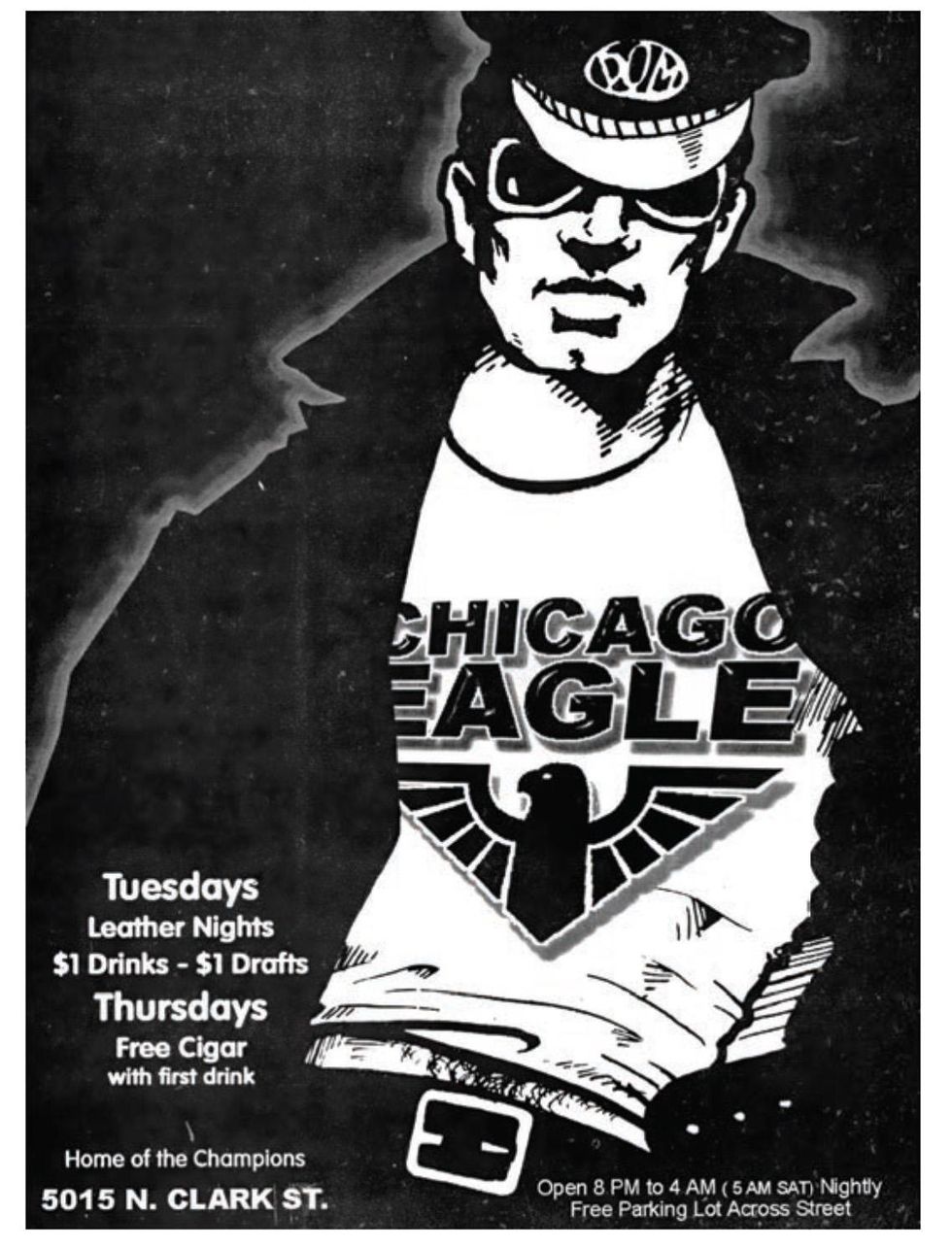

Chicago Eagle, circa 1993-2006. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 45

This complicated relationship between the cops and the gay community led to some arcane rules for bar patrons. "In the '60s, in some of the bars you had to keep your elbows on the bar," de la Croix said. "You could not put your hands below the bar, you couldn't touch anybody else at all."

"You couldn't get up and walk from your table to another table with a drink," Karlin said. "If you wanted to go to another table, you had to go, and then the bartender had to bring your drink over."

Nobody's Darling, circa 2021-present. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 145

As cultural and political changes came to the city, the local bar scene changed too, providing important meeting places for community and activism.

"In the '60s when women's liberation started in Chicago, women were sick of going to these Mafia bars," de la Croix pointed out. "[Bar owners] were trying to get lesbians to go there and they would put pictures of showgirls on the walls with their breasts hanging out. So women started their own coffee shops. And then when AIDS came along, you knew about AIDS because there was all the fundraisers in the bars, and they would raise money for DignityUSA, the Catholic group. It's not about alcohol at all -- it's about gay life."

Glory Hole, circa 1972-1987. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 83

In recent years, the LGBTQ+ community's relationship with bar culture in Chicago has changed, with younger generations using online spaces to connect with each other and being less tied to specific neighborhoods and businesses.

"One thing we've been asked before is how young people don't go to gay bars as much anymore," Karlin said. "They just go to any bar they want to because they feel comfortable doing that, which is what we fought for all those years -- that gay people could go anywhere and be accepted anywhere.

"Unfortunately, now it's biting the gay business community in the ass, because people don't feel as much of a need to go to gay bars. Between that and social media, going out cruising is not what you do anymore. You do it on your apps."

Photo: Sidetrack / Instagram / ART AND PEP documentary

Jose "Pep" Pena and Art Johnson, owners of the famous Sidetrack bar, wrote a foreword for Last Call Chicago about the tension between queer activism and bar culture, with "newly minted activists [who] wanted to abandon all old ways, including 'top down' bar owners who had often been de facto community leaders." So far, however, the feared "epic split between Chicago gay bars and modern gay activism" has not happened.

"In Chicago, the bar owners tend to be really invested in the community," Karlin said. "Art [Johnston] who owns Sidetrack, the most popular bar in Chicago, would give tons of money back to various causes. They basically ... I wouldn't say blackmailed, but strongly encouraged liquor companies to become active and donate money. If they don't, they don't carry them in their bar. They used their clout in a good way."

"There's always disagreements in the gay community, that's how we advance," de la Croix said. "In the early '70s, women didn't even talk to men; there was separatism and all that. It's discussion and even conflict that moves things forward."

Loading Zone, 1978-1986. Last Call Chicago by Rick Karlin & St Sukie de la Croix, Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2022, p. 124

Now, as bars and restaurants across the country attempt to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, Chicago's queer bar scene has decades of resilience to fall back on.

"I think in Chicago there will always be a gay entertainment district, because they learned their lesson early on and started buying the properties when they moved in to what is now known as the Halsted area and Andersonville," Karlin said. "They actually bought the properties, so they don't get priced out as much. I think there will be less of that transience and it will be kind of like any other area -- it will depend on if they keep up with what the people are looking for at that time.

"Hopefully the pandemic is somewhat over, or it's on the edge at least, and things will pick up again and they'll be back in business."