In this excerpt from his new book, the gay intern who worked for Rep. Gabby Giffords recounts the day the congresswoman was shot and how he stepped up to help save her life.

February 05 2013 5:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Saturday Morning

"Gun!" someone said, and it clicked: I remembered some of the things that had happened over the past several months. There had been a campaign event where an angry constituent had brought a gun but had dropped it. And the door of Gabby Giffords's congressional office in Tucson had been shot at last March, after the vote on health care. Gabe Zimmerman, Gabby's aide, had come up to me that morning and said, "If you see anything suspicious, let me know."

So I heard shots, and the first thing I thought of was Gabby -- making sure she was OK. I was about 30 to forty feet away from the congresswoman. I heard the shots and ran toward the sound.

I don't consider myself a hero. I did what I thought anyone should have done. Heroes are people who spend a lifetime committed to helping others. I was just a twenty-year-old intern who happened to be in the right place at the right time.

That Saturday, January 8, 2011, started like an ordinary day. I got dressed in business casual clothes: shirt, argyle sweater, khakis -- what I wear to the office. Gabe Zimmerman had organized a Congress on Your Corner event at a shopping center just north of Tucson. Representative Giffords liked to meet her constituents in person and talk to them about what was on their minds, and discuss what was happening in Congress that they were concerned about. Weeks before, I had applied for an internship at her office, and they had accepted me halfway through the interview. I was supposed to start on January 12, when school was scheduled to begin. I'm a student at the University of Arizona and major in political science. But the office was short-staffed, and I'd volunteered to start early.

I had known Gabby for years. I'd worked on her campaigns since I'd met her in June 2008. She's the kindest, warmest individual you will ever meet. "I don't do handshakes, honey," she always says. "I do hugs."

Gabe had asked me to be at the Safeway market at the corner of Ina and Oracle by 9 a.m. to help with the setup. By mistake I went to the wrong Safeway and didn't get to the right one till 9:30. Everyone else on staff was already there, and they were almost done with setting up folding tables and a few chairs in front of the store. I put a sandwich board outside the market near the entrance that advertised the event. Then I helped Gabe hang a banner from poles that read, "Gabrielle Giffords, United States Congress," and the Arizona flag and the American flag. I made sure we had pens that were actually working so people could sign in.

Ever thoughtful Gabe was the consummate social worker. He was beloved by all who knew him for his kind heart and the good head on his shoulders. He was what we called the Constituent Whisperer, because he had the uncanny ability to take even the angriest constituent and calm them down.

It was cold that morning but clear. Pam Simon, the community outreach coordinator, went into the market for coffee. Before she went she asked Gabe if he'd like anything. But Gabe said no and instead made sure to ask her if she had asked me if I wanted anything. I thought it was so incredibly sweet of Gabe to ask Pam on my behalf. Sometimes interns are forgotten in situations like this.

When constituents started arriving, they had to go through me. I was standing with my clipboard to register them at the back wall of the market close to the adjoining Walgreens drugstore. That's where they had to get in line. Gabby was about forty feet away near the entrance to the Safeway market. As people lined up waiting to speak to her, they wrote down their names, addresses, and phone numbers. We were keeping track of how many folks stopped by and how many lived in the district. I talked to everyone.

A girl named Christina-Taylor Green was there with her neighbor Suzi Hileman. Suzi signed in, and I made sure that Christina-Taylor got to sign in too, because she was so young and so excited to be meeting a congresswoman. I asked Christina-Taylor how old she was, and she told me she was nine. And I asked her what school she went to, and she said Mesa Verde Elementary. We talked briefly about her being on the student council. Then she said she wanted to ask Gabby a question, but she didn't want to ask something stupid and needed help. We had information on the table that had been issued, in the form of press releases, on the accomplishments of the congresswoman. Even though it was way over Christina-Taylor's head, I gave her copies of three different press releases.

Then I went to the back of the line to continue registering people.

Gabe had set up stanchions, the metal poles with polyester bands that are used at banks to help customers form lines. He liked to have them at events so that we had a clearly defined entry and a clearly defined exit. There were chairs against the brick wall where those at the very front could sit before speaking to the congresswoman.

At 9:55 Gabby pulled up in her car. At ten o'clock she greeted everyone and said, "Thank you for being with us on a chilly Saturday morning." She wore a bright red jacket. Gabe stood nearby in case a constituent were to ask for help from the office. Ron Barber, Gabby's dedicated district director, stood at her side as well, listening and watching proudly as his boss carefully and adeptly talked with constituents. Jim and Doris Tucker were at the head of the line, but the first person who actually spoke to her was Judge John Roll. He had stopped by to say hello. Then she talked to the Tuckers and Dorwan and Mavy Stoddard.

Meanwhile, at the back of the line, I checked in Bill Badger, a retired army colonel. Although he was a Republican and Gabby was a Democrat, he admired her and knew she would answer his questions.

I had just checked in Bill Badger when I heard what I thought was gunfire. It was 10:10 a.m. For about half a second I thought, Oh, maybe it's fireworks. Then I heard someone say, "Gun!"

Stop the Bleeding

There was blood everywhere. Bodies on the ground. Screams. As I rushed toward the sidewalk in front of the market, I passed the gunman. I saw him shooting with a pistol. He was running away through the entry line we had set up outside, and I was running through the exit. The whole time he was continuing to fire into the line of people who were there to see Congresswoman Giffords. He was indiscriminately shooting.

I'm big, but I didn't think of tackling him. In that split second I figured it was more useful to go to the front, where people had been injured, than to try to stop him. I didn't know how many weapons he had, and I didn't know how many rounds he had left in his magazine. It was probably not the best idea to run toward the gunshots, but people needed help. I had limited medical training in high school and knew that people could bleed out in seconds from gunshot wounds. When I went to the front, it wasn't just to find Gabby; it was to find out who was injured. I knew that Gabe and other staffers were in the vicinity too.

I checked for pulses in the two victims closest to me. First the neck, then the wrist. Gabe Zimmerman was dead. Ron Barber was on the ground bleeding. He was still conscious, and he was in shock and in a lot of pain. Ron had been shot in the leg and the face. But even at this moment he was asking me to move on and check others who needed more help. "Make sure you stay with Gabby," he said. "Make sure you go help Gabby."

I moved from person to person checking pulses. The first rule in a trauma situation is you do what you can and move on. Ron was in serious condition but not as serious as the congresswoman, who had been shot in the head and was still alert and conscious.

I saw Gabby. At first it looked as though she might be in a defensive position. I had hoped that she had been uninjured, but as I got closer, I saw that she had fallen and was lying on the sidewalk bleeding from a head wound. I quickly started looking around her body to see if there were any other visible injuries. Seeing none, I applied pressure to the entry wound on her forehead with my bare hand.

I pulled Gabby into my lap and helped her sit upright so that she wouldn't choke on her own blood. She was still alert and she was still conscious. That was a good sign. Her eyes were closed and she couldn't talk, but she was moving her right hand and using that to respond. I wanted to make sure she knew what was going on around her. I let her know she had been shot in the head and that the authorities had been alerted. My main priority was to keep her engaged, keep her calm. I kept asking her questions like, "If you understand that the ambulance is coming, squeeze my hand." And she squeezed my hand. I said, "We're going to take you to the hospital. Everything's going to be OK."

While there was a lot of blood, it didn't look like she had an arterial bleed. If she'd been bleeding from an artery, she could have lost a lot of blood in a very short amount of time. Her gunshot wound was through her brain. Not too much blood is lost in that kind of injury. I had learned this in high school when I'd trained to be a nursing assistant and phlebotomist. Although the subject of trauma injuries hadn't been covered in my studies, I had had conversations about this topic with different doctors and people who worked in health care. I had asked questions about anything I thought was interesting.

So now I felt confident that I was doing the right thing for Gabby. After I had been with her for a minute or so, a couple who had been shopping in the market dashed out to help. He was a doctor and his wife was a nurse. They came over to me and checked really quickly to see what I was doing. Dr. Bowman told me to continue applying pressure to Gabby's wound. "Don't let her move around," he said. "Keep doing what you're doing."

Pam Simon was dead. Someone looked her over and said, "She's a goner."

Sirens wailed. Minutes later police and paramedics arrived. The police secured the crime scene with yellow tape before they let the paramedics assist the victims. The police had to make sure there were no other assailants.

Gabby kept trying to move around. When the paramedics were finally allowed to come over to us, they asked me where Gabby had been shot and if there were any other injuries. There was one obvious gunshot wound to the head, but there wasn't any other injury that we knew of. First they had to immobilize her neck. So while she was still in my lap, they put a neck brace on her. They wrapped an Israeli bandage, which was used to stop the bleeding, around her forehead. She still kept moving, so they asked me to hold the gauze in place until they could get more. Then they got a stretcher and put her on it. The paramedics wanted to wait for a helicopter. "What's the ETA?" I asked. They said about 20 minutes. "We've got to get her out of here in the first ambulance," I yelled at them. "She's still alert and responding to commands." Everyone was in shock. There was so much confusion that it helped that I yelled. No one was giving clear instructions. So the paramedics listened when I said, This is what we're doing. I told them to take her to the hospital right away. I held her hand as they hurried her to the ambulance. "I'm going with her," I said to the paramedics.

They told me they could take only family, but I pushed my way into the ambulance. Sirens screamed as we sped along.

Gabby was in a lot of pain. They were trying to get an IV started, but they couldn't find a vein. They poked her repeatedly. She kept writhing around. I think having me there to calm her down helped the paramedics focus on their work. I was trying to figure out what I could do at that point. I told her we were going to try to get ahold of her husband, Captain Mark Kelly, and her parents, Gloria and Spencer Giffords. But I didn't have Mark's number or her family's number. I had a new cell phone, and I hadn't had a chance to put in numbers for people I would have normally called who were involved with the Democratic Party and knew Mark and Gabby.

The only one I could think of was Steve Farley. Steve is the state representative from District 28, Tucson, and I had worked as his campaign manager. I had become friends with Steve and his wife, Kelly, and his daughters, Amelia and GiGi. And he and Gabby were friends. So I called him before I called my parents, and told him what had happened. In the background I could hear Kelly and the girls laughing and saying hello; they were on their way to Kartchner Caverns State Park. I immediately told Steve, "Steve, shut up, stop talking. Gabby's been shot. I'm in an ambulance with her. I need you to call Gloria and her husband. We are headed to UMC. HURRY." I assumed we were going to the University Medical Center because it's the only trauma center in the city of Tucson, and, in fact, all of southern Arizona.

Then I called my parents to let them know I hadn't been injured, but I didn't tell them anything besides that. I knew that they would be frightened, but I also knew that time was limited and it was more important for me to talk with Gabby to try to keep her calm on the way to the hospital. Keeping my parents and sisters informed was secondary to my job of tending to Gabby.

When we reached University Medical Center, the ambulance doors opened. The medical staff rushed Gabby into the hospital and told me to stand there and stay still. Sheriff's deputies said, "Someone will be with you shortly." They said I wasn't allowed to talk to anyone or use my cell phone or interact with anybody until the sheriff's deputies questioned me.

People had started to gather to see what was happening. Media trucks began to arrive.

My clothes were covered in blood.

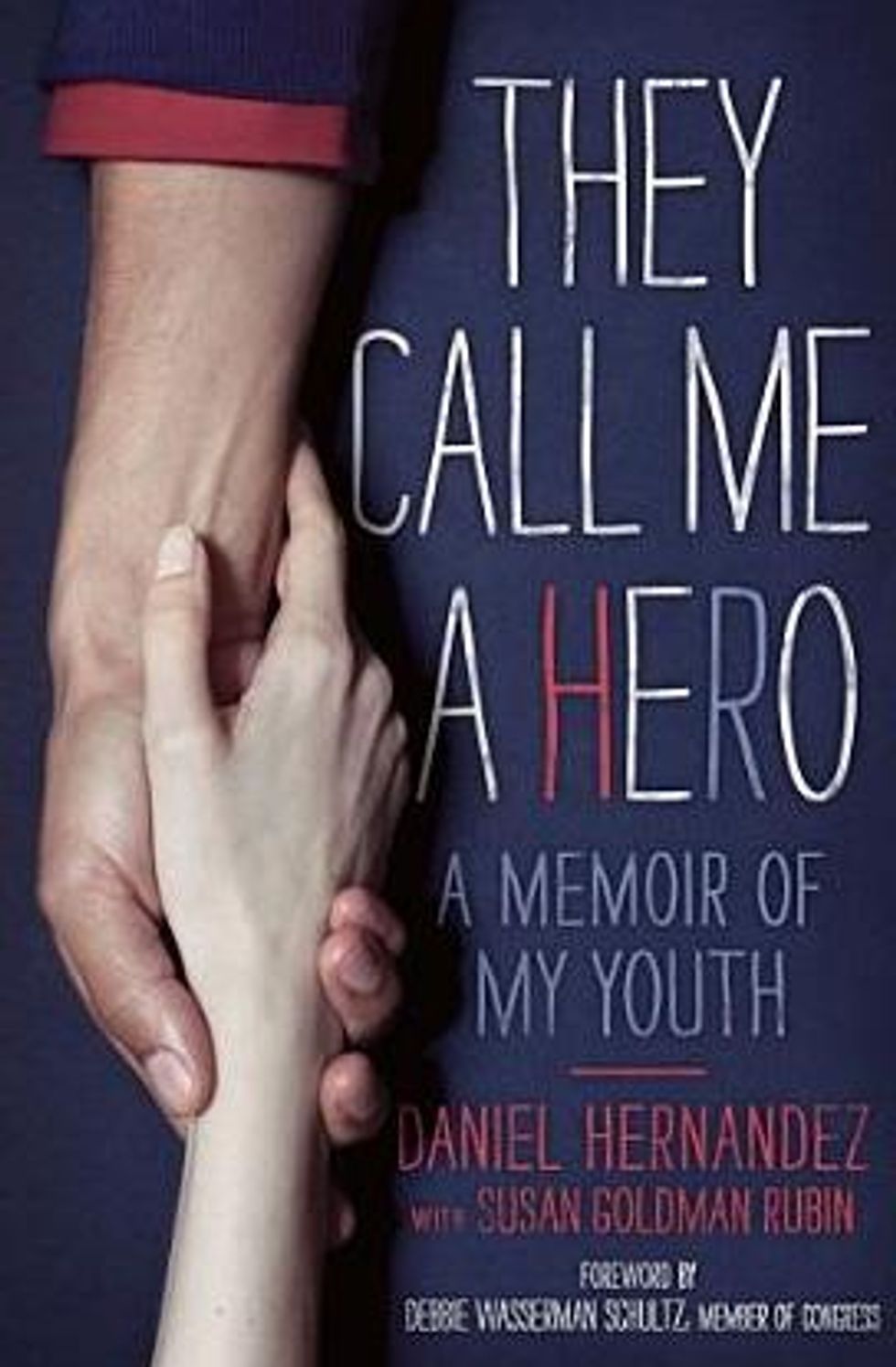

Excerpted from They Call Me A Hero: A Memoir of My Youth by Daniel Hernandez, with permission from Simon & Schuster.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes