Growing support for gay rights by conservatives and Republicans has reinforced a dubious political narrative: that there are fiscal conservatives and social conservatives and only the latter are antigay. But Niall Ferguson's bizarre attack on the personal life of economist John Maynard Keynes has exposed the nasty moralizing aspect of fiscal conservatism. Indeed, it's revealed a deep philosophical connection between social and fiscal conservatism and suggests the presence of unconscious homophobia at the root of the conservative mind.

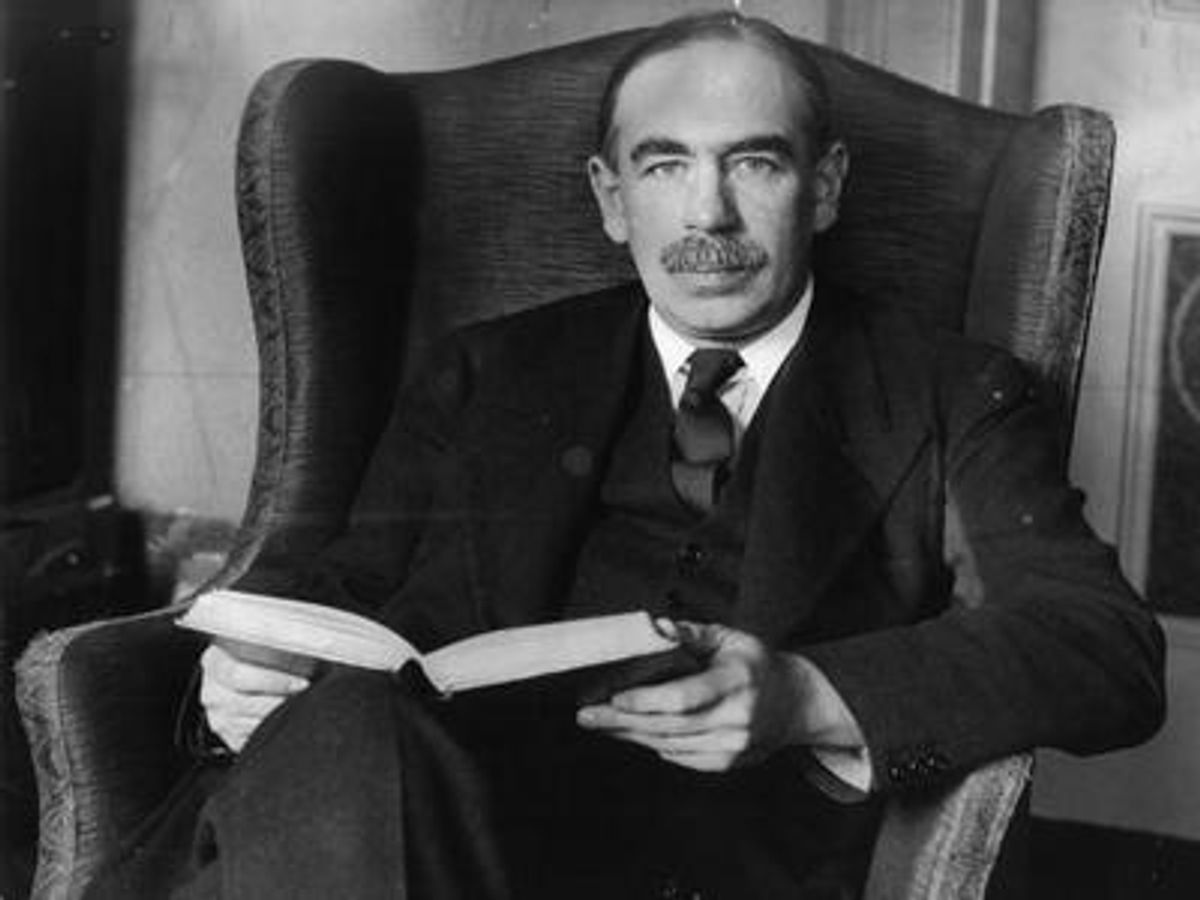

Ferguson's controversial comments centered around Keynes's famous remark that "in the long run, we're all dead." Ferguson, a Harvard historian who studies how empires decline, told an audience of 500 that Keynes's economic worldview grew out of his personal experience as a childless homosexual. According to reports, Ferguson cast Keynes as selfish and "effete," concerned more with poetry than progeny. His logic was that the economist favored high debt and short-sighted consumption over the more virtuous Protestant ethic of saving and self-denial because childless gays are less invested in the future. (Apparently Ferguson forgot the advice of heterosexual father George W. Bush following the 9/11 terrorist attacks: to go shopping.)

Ferguson apologized Saturday for suggesting that Keynes developed hedonistic economic beliefs because he was a childless gay with no investment in the future. He stated that he would never dismiss Keynes's economic beliefs by impugning his sexuality, and he claimed to "detest all prejudice." But evidence quickly materialized that Ferguson has a history of making precisely such dubious and disparaging links.

Recognizing the gravity of his misstep, Ferguson penned a longer letter to the Harvard community. In his open letter to the Crimson, Ferguson resorts to a version of the "some of my best friends are black" defense against prejudice. Indeed, Ferguson previously fought allegations of racism for comparing President Obama to a black cat, and his retort was he couldn't possibly be racist because his wife was born in Africa. Likewise, he wrote this week that he couldn't possibly be antigay because he asked a gay person (Andrew Sullivan) to be his son's godfather.

To Ferguson, these personal facts about his bio make the charges of bias "easy to refute." But I don't think they do. To be clear, I do not wish to join the chorus of critics who call Ferguson's remarks "gay bashing" or who angrily hurl the epithet "homophobe" at anyone who goes off-script about gay people. Indeed, I'd like to make this script less, well, scripted, and encourage our culture to learn from the feelings that words express instead of censoring the script.

On this, Ferguson and I agree. He says we can confront prejudice through "repression" or "education" and, correctly, chooses education, touting his own efforts to condemn eugenics, homophobia, and anti-Semitism. But just what are we to make of his having said these things in the first place? Ultimately, Ferguson gives us zero explanation for how these things could ever have come out of his mouth, simply dismissing the words as the "stupid things" that we all occasionally say.

The problem with Ferguson's explanation is that he entirely misses the difference between taking a position and having a feeling. And he misses this distinction in a surprisingly unthoughtful way. "There is still, regrettably," he writes, "a great deal of prejudice in the world." But he doesn't seem capable of applying this critique to himself.

The difficult truth is that it is very possible to love people and hold nasty and incorrect views about them at the same time (or nasty and correct views, for that matter). In fairness, if this is Ferguson's failure, it's reflective of a larger failure of our culture. Too often we prefer the WASPy dinner party to the revealing -- and healing -- heart-to-heart, opting for everyone to say the polite thing rather than to get to the bottom of the issue. As Ferguson writes, "To be accused of prejudice is one of the occupational hazards of public life nowadays." And if, in writing this, I am insisting that, of course Ferguson must be kinda antigay, I'm compelled to add that none of us is immune to prejudice.

At left: Niall Ferguson

At left: Niall FergusonStill, it's a particular sin of American conservatives, who have a long history of defining gays (and liberals) by their immorality, specifically their supposed inability to control their desires. This is probably an important source of conservatives' newfound hatred of deficits: the need for a scapegoat for their doctrinaire belief that America is ever threatened by untamed desire.

In a revealing National Review piece, Jonah Goldberg, a Fox News contributor, provided a number of instructive examples of conservatives identifying Keynes's economic beliefs with his suspect sexuality. Gertrude Himmelfarb, he points out, claimed that Keynes's views had "an obvious connection with his homosexuality" and his "childless vision," which she also linked to the "Keynesian doctrine that consumption rather than saving is the source of economic growth." She found a "discernible affinity" between Keynes's "premium on immediate and present satisfactions" and Keynesian economics, which, she (wrongly) claimed "is based entirely on the short run and precludes any long-term judgments."

Calling Keynes "a Bloomsbury aesthete and a practicing homosexual," George Sim Johnston wrote in 1986 that the economist "did not believe in self-denial" nor that he "had any obligation to posterity," adding that was only natural "if you have no children and don't want any." If Keynes had disclosed all this, complained Johnston, "we might have lower federal deficits." One editor even theorized that Keynes's sexual morality led him to reject the gold standard.

Critics of Keynes are fond of citing his own self-description as an "immoralist" to justify their distaste for his allegedly hedonistic theories. But they consistently quote him out of context -- or genuinely misunderstand his principled moral critique. Goldberg maintains that "Keynes himself" described the mindset of his peer group "as a rejection of all standards" and quotes the following: "We repudiated entirely customary morals, conventions and traditional wisdom. We were, that is to say, in the strict sense of the term, immoralists," recognizing "no moral obligation on us, or inner sanction, to conform or to obey."

What Goldberg leaves out is a key phrase just before the ones he quotes: "We claimed the right to judge every individual case on its merits, and the wisdom, experience and self-control to do so successfully." You might call this arrogant, but it's simply not a rejection of morality, per se. It's a rejection of mindless conformity, in favor of a deliberative, particularized assessment of what is ethically obligatory in a given situation. Indeed, the passage was part of an earnest and tough-minded effort to think rationally about moral obligations, a project that's far more admirable than the simple process of following rules drilled into you on your mother's knee. Keynes wanted to subject the rules of tradition for tradition's sake to the light of reason.

Elsewhere I've written of a growing body of evidence that homophobia operates in subconscious regions of the brain and that the stories told by antigay people about gay people are efforts to rationalize intuitive antigay sentiment. By all accounts, that appears to be happening here. Keynes's support for deficit spending is cast as a product of his hedonistic sexuality, while Adam Smith's virtually identical praise for self-interest and the virtues of consumption are simply empirical observations about the natural processes of the invisible hand. Keynes is viewed as a dangerous champion of debt and consumption when, as Paul Krugman points out this week, Ronald Reagan and the two Bushes were the only presidents of the last 10 who left office with a higher debt ratio than when they came in. And Keynes is cast as a lover of debt while critics entirely ignore the critical other half of his philosophy: that while you should run deficits in hard times, you should pay them down in good times. As Matthew Yglesias writes in Slate, the idea that Keynes was a short-term thinker is absurd, as he was "one of the deepest thinkers about the long-term economic trajectory of all time."

Getting Keynes this wrong is no small matter, because it raises the distinct possibility that even "serious" thinkers are pouncing on a narrative that confirms their antigay biases but does little to advance the truth. It's a damning pattern of conservative thought we'd do well to call out when it happens. Not so we can censor its expression, but so we can guard against dubious policy conclusions, and -- if we're lucky -- so we can nudge people to examine their own harmful biases.

The point is not that all conservatives are homophobes, but that a persistent feature of both fiscal and social conservatism -- what ties them inextricably together into one worldview -- is a deep distrust (one might call it a fear) of desire, a sentiment that harks back to our founders' concerns that stability in a democracy relied on citizens' ability to keep their impulses in check. This may or may not be a valid concern in the 21st century. But one thing that should be clear is that gay people have no more trouble controlling their desires, or acting responsibly toward the future, than anyone else. Suggestions to the contrary say far more about the psychology of straight people than the reality of gay people.

NATHANIEL FRANK, author of Unfriendly Fire, is a visiting scholar at Columbia's Center for Gender and Sexuality Law and a frequent contributor to Slate.

At left: Niall Ferguson

At left: Niall Ferguson