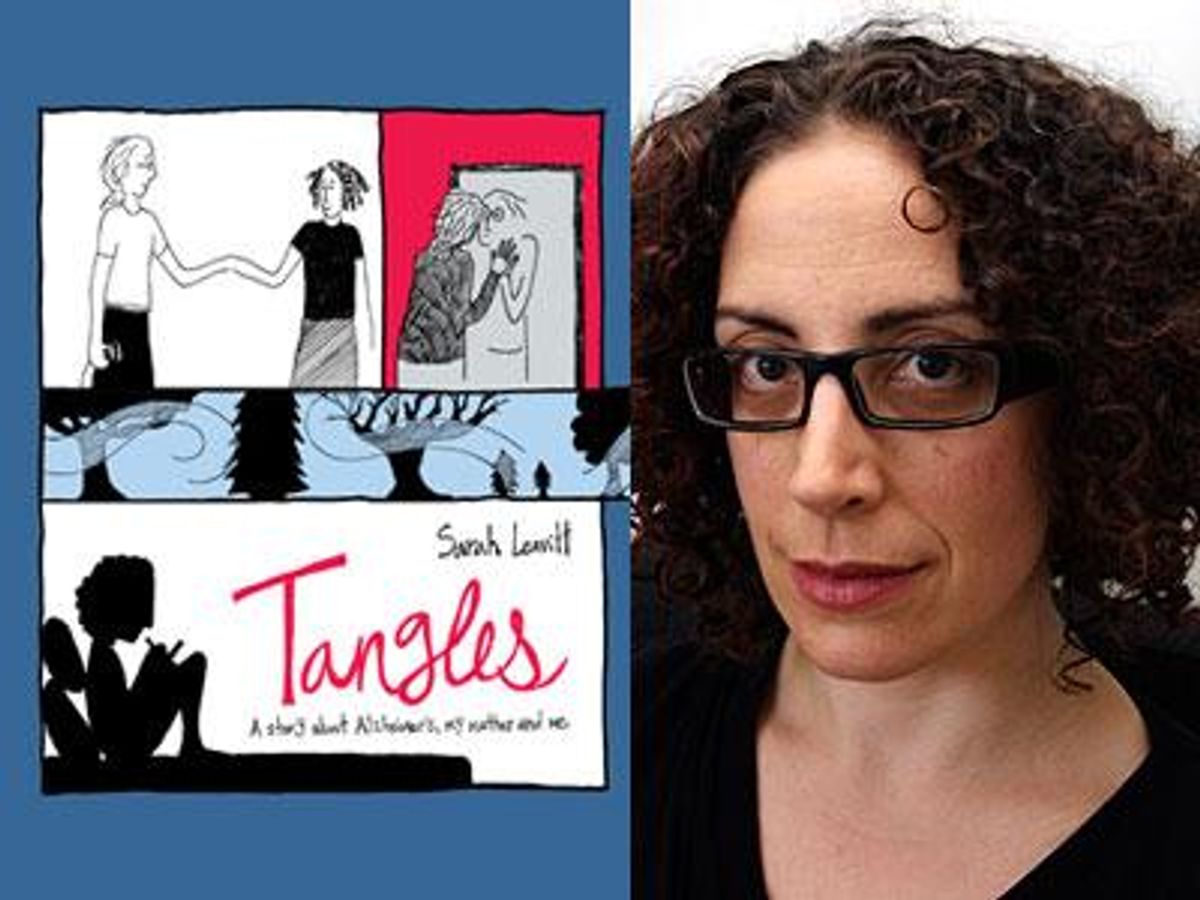

Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer's, My Mother, and Me is a graphic memoir by lesbian cartoonist-author Sarah Leavitt about losing her mother to Alzheimer's.

Today 5.4 million Americans are struggling with the terminal disease that is personally impacting more and more of us. My own grandma died of Alzheimer's in 1999, the same year Leavitt's mother was officially diagnosed.

Most people know that Alzheimer's is a progressive neurological disease that eats away at a person's memories. The Alzheimer's patient is commonly portrayed as no longer recognizing their own loved ones.

In reality, Alzheimer's is far more devastating.

As Tangles (Skyhorse Publishing, $14.95) illustrates, people with Alzheimer's often forget what everyday objects, like keys or silverware, are used for, not where those items may have been stored. They often lose what we think of as muscle memory as well, forgetting how to do common, almost reflexive physical actions like getting out of a car or brushing their teeth.

Worse, Alzheimer's doesn't just delete memories; in some ways the disease steals away the person themselves. It slowly erodes their personality until eventually, everything that made that person uniquely themselves has been washed away. For me, that became crystal clear the day my conservative and pious 84-year-old grandma began cursing and screaming at the TV, yelling, "That fucking slut" whenever Deanna Troi showed up on screen as we watched Star Trek: The Next Generation.

For Leavitt, this happened when her animal-loving mother didn't even notice that the car she was in had hit a stray dog. She describes her mother slowly receding into the distance as everything that made her began to fade.

For some readers, the real-life story that Tangles explores in sparse black-and-white drawings and straightforward prose will be a realization of their greatest fears.

For one thing, Leavitt's mother suffered from early-onset Alzheimer's. She was diagnosed at a relatively young age -- 52 when her symptoms became obvious -- and her illness progressed quickly. She passed away soon after turning 60. (My grandmother was 90 when she died). Before Alzheimer's, Leavitt's mother was a whip-smart, active, and engaged woman. She had attended Radcliffe College, was a renowned teacher in Canada, and ended up working for the New Brunswick government designing the curriculum for all of the kindergartens in the providence.

There's something particularly painful about watching a brilliant mind dissolve. And although many researchers believe that keeping the mind active can actually delay Alzheimer's, Leavitt's mother was still working when her mind deteriorated.

The fact that Leavitt's mother was such an intelligent, quick-witted woman meant that she was quite aware that she was losing her faculties. That awareness made the process all the more difficult for her; she was angry and bitter and lashed out at those closest to her. She didn't want to need their help.

Caring for someone with Alzheimer's is no easy task, and Leavitt doesn't shy away from sharing how hard her mother's illness was on their family. The disease is particularly difficult on caregivers who are related: spouses, children, siblings. As Leavitt bravely reveals in Tangles, suddenly the boundaries and intimacies that previously defined those relationships began to blur.

At some point her parents' room is no longer their sanctuary; her mother's naked body is no longer reserved for her husband's sexual gaze. Sexuality itself loses meaning. In so many ways, his wife is no longer his and no longer a wife. She reverts to an almost infantile stage but remains in the body of an adult woman, making caring for her at home increasingly difficult.

In disrupting relationships and stealing away the loved one's soul, Alzheimer's often leaves caregivers grieving years before the person's body finally succumbs to the disease.

There is one silver lining to the progression of Alzheimer's: Eventually Leavitt's mother is no longer aware of her illness and what it is costing her. With the loss of her cognitive functions, her anger dissipates.

Throughout this story of death and loss Leavitt also weaves her life: coming out as a lesbian, falling in love, exploring her Jewish identity, finding faith, and watching -- somewhat resentfully -- as her straight sister benefits from the privileges of heterosexuality, including legal marriage and biological children.

Life goes on.

Of course, this doesn't mean that life is full of sunshine and happiness. Leavitt may be a cartoonist, but she admits to some darker impulses: cutting herself, wanting to drive into oncoming traffic. She acknowledges being overwhelmed, resentful, and angry. She describes walking through her life like a zombie. For Leavitt, life is complicated. But there is something beautiful in its knotted ugliness, like the tangles of her mother's hair that Leavitt collects.

As tragic as her mother's death is, in creating this graphic memoir, Leavitt shares some of the wonderful, funny, and touching moments that were also a part of her entanglement with Alzheimer's.

And she gives us two important lessons: One, cherish the moments you do have, and two, don't put off planning for the realities of old age and death -- but keep in mind that things may not turn out as you hoped. As Leavitt's father says, "Sometimes it turns out that everything you thought about how the future would be just isn't true."

Still, the more prepared we are, the quicker we can provide our loved ones with the care they need. The more we acknowledge that disability and death await us all in the end, the more we may cherish the (able-bodied) moments we do have.