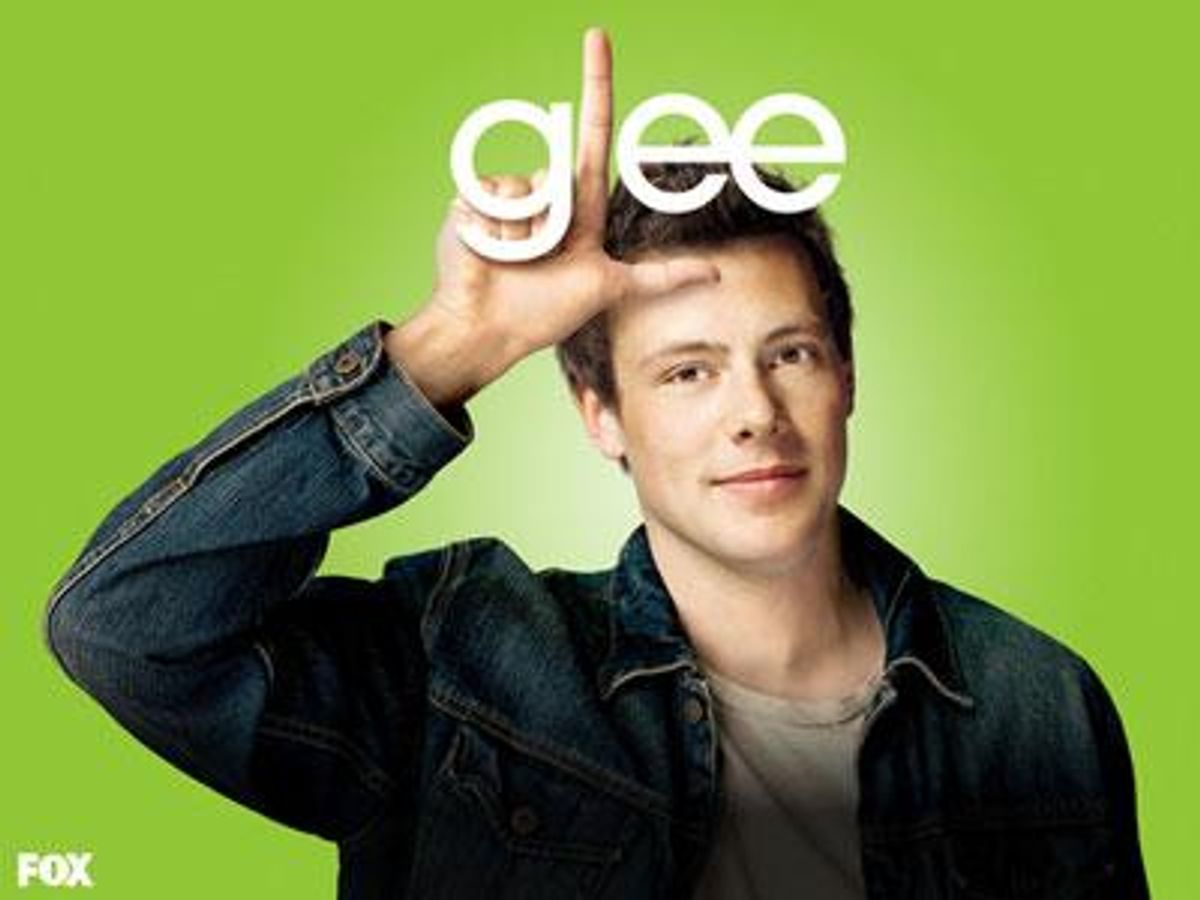

When I first saw a Facebook post featuring Cory Monteith making an L-shape on his forehead in signature Glee promo fashion, I thought Fox canceled the show. But, as I scrolled through my feed and saw the same photo with "he was so young" written again and again, I realized Monteith had died. But then I thought, these statuses could have been about my own potential relapse.

At 26, I'm a recovering alcoholic, two years sober. Earlier this month, Monteith died at age 31 in his room at Fairmont Pacific Rim Hotel. Toxicology reports show the cause of death was mixed drug toxicity, involving heroin and alcohol. "He did it to himself," a friend's status read. "He snorted his life away." This comment was a reminder on how people really feel about recovering addicts like me.

Months ago I read that Monteith struggled with substance abuse issues, and it immediately made me relate to him more. As Finn Hudson on Glee, he came off as whiny and pedestrian and too much like the boys in high school who made me feel lesser. Knowing Monteith had an addiction made him more real to me. That probably sounds cruel or evil, but knowing that a fresh-faced TV star shared similar struggles, gave me some type of comfort. It bonded us. If you've ever felt out of place somewhere, then you might know what I mean.

Like him, I abused alcohol in my teens. Like him at age 19 I went to rehab (mine an outpatient treatment, court-ordered because of a DUI). Like him, I got sober. Recovering -- the "ing" means a constant and evolving state. Even if I'm not still using, it's there. It's a mental state. Like him, relapse is always a possibility.

People on my Twitter and Facebook feeds expressed confusion and shock over Montieth's death. He wasn't a hot mess in the media like Amy Winehouse, a celebrity whose addictions unfortunately made almost as many headlines as her immense talent. Monteith looked fine and healthy and normal. I never heard any stories about Monteith getting kicked out of clubs or driving around with liters of vodka in the passenger seat. His death made me think of addicts I know with spouses and kids and jobs as accountants. Everything in their life seemed controlled until one day they passed out in their front lawn during a child's birthday party. Montieth seemed to keep it together, at least publicly. Before I quit drinking, I went through a period of "perceived stability" or more accurately called: secret binging. When it comes to addiction, someone doesn't have to look out of control to actually be out of control.

A few days before Monteith's death, a friend and I talked about her recent heroine relapse. As these things tend to go, a one-night indulgence turned into a three-week binge.

"Nothing scares me more than relapsing," I told her. "It sneaks up on you."

For me, a healthy fear of relapse helps keep me sober. Most people don't plan their relapse - it can happen on a random Tuesday night when you go to the corner store to get Sour Patch Kids and cigarettes and end up with a jug of wine. Addiction is a progressive disease, which means that it gets worse with time. A lot of non-addicts don't want to talk about it that way, acknowledge it's not as easy as "putting down the bottle." We have to learn to deal with stuff like going to a dinner party and passing up the wine. We have to re-learn how to function in society. We have to re-program ourselves.

When a celebrity dies of an overdose, people usually lament the loss of talent, not the actual person. In Monteith's case, people wonder how they'll write Finn out of Glee. This is the truth for any addict -- a young addict, especially, because we are known to be selfish and destructive. The stigma around addiction still moves the conversation toward "he did it to himself" like you can turn off addiction whenever you want. The danger in this type of thinking is that it stops dialogue surrounding healthy ways to deal with addiction. I understand the cynicism. We usually are toxic people when actively using, but the sentiment trivializes our struggle.

In March, Monteith voluntarily checked into rehab, a sign that he was struggling but still trying to work on his issues. His openness about addictions was commendable and brave. He starred on a wildly popular show about high school, he didn't have to ever publicly address it. By doing so, he saved kids's lives because his honesty showed addiction can happen to anyone. He was working on it and he let other people know it's OK to be working on it.

While I never met Cory Monteith, I've known plenty of people like him. He is in my friend who talks to me about her problems on a Friday night, he is your former roommate, and he is someone like me. We need to examine how we address addiction, and not just assign blame to the deceased. Not every addict relapses, but some people do. Some die from it, others don't. For those who do die from it -- celebrity or not -- I hope we can move toward remembering what addicts did as people and not just as their disease.

TYLER GILLESPIE has written for Out, the Chicago Reader, Time Out Chicago, The Huffington Post, Windy City Times, Splitsider, and Paste, among other outlets. He is currently finishing a memoir about his younger brother who has Down syndrome. Follow Tyler on Twitter @TylerMTG or Tumblr.