The United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs has recently been working to overcome backlash from a revelation that a therapist with a long and active history in "ex-gay" ministries was leading the academy's mandatory cadet counseling program. Academy brass contend that the therapist in question, Mike Rosebush, Ph.D., does not directly counsel cadets, but he reportedly developed the academy's "Character and Leadership" coaching curriculum, which every cadet who hopes to graduate from the academy must complete.

The academy issued a joint statement with members of the institution's gay-straight alliance, Spectrum, contending that the academy was a "safe and welcoming place to be [gay lesbian, bisexual, queer or questioning]," and insisting the articles reporting on Rosebush's involvement "do not take into account the extensive support our LGBQ cadets have received from Academy leadership or the reality of the Academy's inclusive environment."

LGBT people are likely to notice one letter conspicuously absent from the acronym used to refer to their population -- and that's because military policy still bars transgender Americans from serving openly in the armed forces. When "don't ask, don't tell" was repealed in 2011, it had no impact on the military medical regulation that deems a transgender identity or any gender-confirming clinical treatment indicative of a mental illness that makes one unfit to serve.

But that doesn't mean there are no transgender people in the military, or even at the nation's hallowed military academies. As a former midshipman, Navy veteran, and activist who happens to be transgender, I am in contact with several transgender cadets and midshipmen who continue to be in the closet at these institutions.

In the wake of the latest Air Force controversy, I reached out to these students and asked them to share what conditions are like for them as closeted cadets and midshipmen at various military academies. Read their first-person responses on the following pages.

At left: Members of the graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point stand during graduation ceremonies May 22, 2010, in West Point, N.Y.

At left: Members of the graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point stand during graduation ceremonies May 22, 2010, in West Point, N.Y.

Kyle, a transgender man who graduated this year from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, writes:

There are two types of hiding -- the kind that requires you to lurk in the dark spaces of the day, behind shadowy places, and from your own memory; and there is hiding in plain sight.

The latter is a sort of hiding out loud. It's liberating and at the same time denigrating. That is what is required of you if you are a proud and well-adjusted transgender person serving in the military. You can be you, so long as no one actually sees you -- the real you -- for who you are.

As a transgender [female to male] cadet at USMA, my experience was uniquely wonderful and simultaneously awful. I was never hazed or even disrespected (to my face). No one ever bothered me -- past freshman year, where being bothered is standard. I was always treated fairly. The ideals of excellence and meritocracy were promoted and reinforced over and over again as I was rewarded with several amazing opportunities -- even a cadet command position my senior year. I could be the best me as long as I wasn't the real me or honest about who the real me was. That was a funny thing at an institution that prides itself on excellence and honesty.

The more I achieved and was noticed, the more I was forced to endure the daily indignity of being silent about who I am, even with people I knew and who knew. I began transitioning while a still a cadet, so everyone noticed changes. Some classmates, and even instructors, who I viewed as mentors told me that they understood, but that they could and would not recognize who I was -- "for my safety," of course.

After I sidestepped all the fear and used all the courage I had to come out to them, they continued to misgender me, "for me." There's a different kind of indignity in being disallowed your identity. To be denied your identity means to be denied both the joy and pain of your living experience. That kind of denial transcends identity. It becomes a disavowal of your humanity.

When DADT was repealed for LGB soldiers, it was a feeling [among enlisted trans people] that, I would guess, is akin to never being picked for a team or being publicly bullied. Those are the instances that come to mind when I try to think of the kind of heartbreak that is accompanied by public humiliation. That's the worst kind of heartbreak. You endure the gossip while being precluded from addressing it. You endure the stares while never actually being seen. You endure the daily reminder that no matter how good you are, you will never be good enough.

And that is a painful thing -- for the full spectrum of your identity, the full weight of your humanity, to never be recognized; to be proud of who you are and have to live out loud in the darkness of other people's shame. I rebelled as often as I could, but you can only do so much living in the shadows of who you are.

At left: The midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy march onto the field before a game between the Army Black Knights and the Navy Midshipmen last Saturday at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia.

At left: The midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy march onto the field before a game between the Army Black Knights and the Navy Midshipmen last Saturday at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia.

Kris, a transgender midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., slated to graduate in 2014, writes:

Before I enlisted, I thought I was straight. During DADT and while I was in A-School [enlisted trade school after boot camp], I figured I was a lesbian. After DADT was repealed, I saw little change. The big thing was that they couldn't kick us out for being gay anymore. But people could still give us the cold shoulder, they could still disagree with us in a very loud way, they could still tell us that we were going to hell because we are gay.

About a year ago, I went back in the closet; I started figuring out that I am transgender. It's something I should have probably figured out a very long time ago, but it's not surprising, considering how late I figured out that I was a lesbian. My fiance helped me out and is my closest ally. But I can't talk about it in the Navy. I get a short haircut, and people make fun of me. I go to the women's restroom and I get looks, yelled at, or even physically pushed out of the bathroom.

I even get called out on the first day of class when the professor calls roll:

Professor: "[Calls my last name]"

Me: "Here, sir."

Professor: "No, this is for [female name.]"

Me: "Yeah, I got that. I'm still right here."

People say that it's all in the haircut, but that's not true. Even when I had long hair and kept a bun, I was constantly called "sir" and would surprise women when I walked in the bathroom. I am who I am, and no one can change that. I hate that I am back to lying to my classmates and my coworkers.

I hate that I have to lie at all. As a prominent member of Navy Spectrum [the GSA at the Naval Academy] I am constantly told by members and by my leadership that I have to "watch it on the trans stuff," since the military doesn't accept it. Hell, even with our "Safe Spaces" program, we have just been told that we cannot incorporate transgender. Of all the people who need a safe space, transgender midshipmen are on the top of the list.

It took us until this semester to finally get the truth that our counseling center was a safe place for transgender midshipmen. Luckily, a few of us are trusting it and attending regular sessions there. I personally attend a session every week for about 45 minutes at a time. My psychiatrist has been doing a tremendous amount of research in order to help me.

Like I said earlier, it sucks, or is highly uncomfortable, being back in the closet. And it will most likely be the deciding factor of whether I stay in the Navy or leave, so I can live my life the way I know I feel. I believe in service and the Constitutional Paradigm, but if the country I serve cannot protect me or at least treat me with some respect, I think it's time I find a different way to serve.

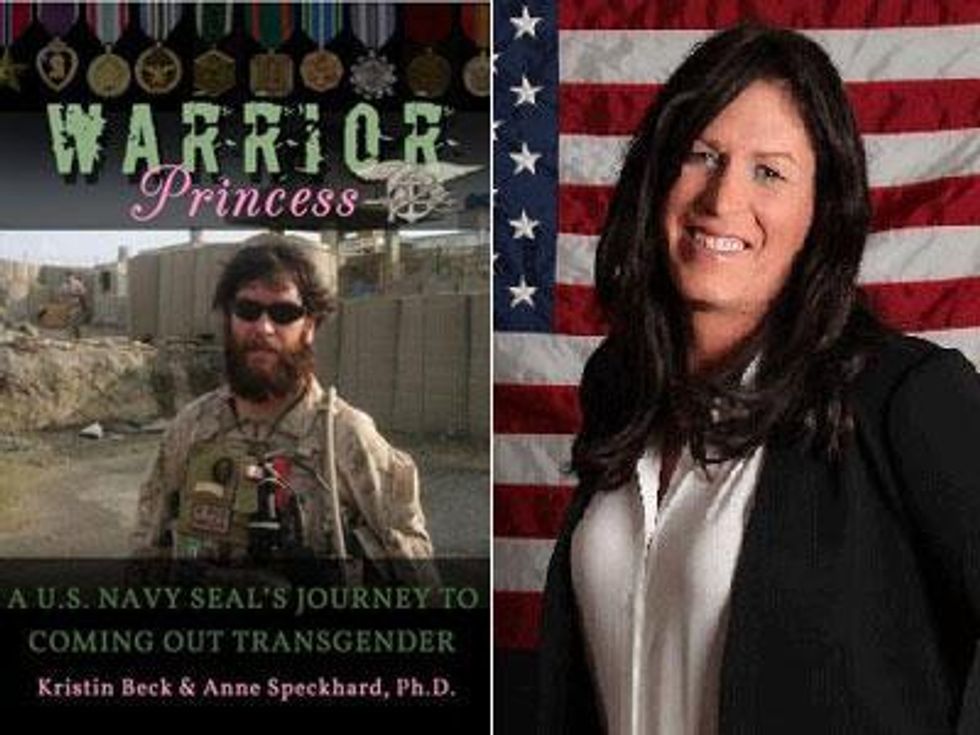

At left: trans former Navy SEAL Kristin Beck.

At left: trans former Navy SEAL Kristin Beck.

Allison, a transgender midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, class of 2015, writes:

I have seen very little hatred toward gays or lesbians from the other midshipmen. Most of them leave the gay and lesbian midshipmen alone or are good friends with them. Yes, there are still some times where someone makes a gay joke, but I don't recall a gay midshipman ever being the butt of the joke, and those jokes are usually discouraged or even reprimanded. This all might just be because of a fear of getting in trouble. With sexual harassment awareness being stressed so much, most people just try to avoid anything that could be taken as harassing gay or lesbian midshipmen. Take note, however, that this is my perspective; I am not out, and those who do not know about me do not suspect me or lump me into the LGBT community. So it might just be that I am oblivious, since I have not had to deal with that personally.

I have noticed, however, that there is still a transphobic attitude from many midshipmen. This is probably just a reflection of general society as a whole. With Kristin Beck coming out earlier this year, a few conversations were started that usually ended up with people considering her to be weird or unnatural.

The other day, my roommate called me over to his desk, saying he had something funny to show me, and then played a video that was very offensive to transgender people. I, of course, had to laugh and say it was funny, but inside I cringed and struck my roommate off the list of who to come out to in the near future. Many midshipmen just do not realize that not only are transgender people humans with hopes, dreams, and feelings, but they could also be some of their best friends. If they could be made aware of this fact by allowing us to serve openly, more people would realize that things they thought were funny could be very offensive to a close friend.

Pretty much all gay or lesbian midshipmen can come out without backlash. The only reasons they may choose not to would be for family or religious issues. I feel that those who do choose to come out get plenty of support from their companies, classmates, and the academy.

Being one of the few who still cannot come out makes it harder for me to get close to those who have come out as gay or lesbian. I sometimes get a sense of pride that I am part of an elite group of people who must keep our identities secret or risk compromising everything, but that doesn't always help make me feel better. The fact that I have to hide who I am to my friends taxes me, and the stress of keeping myself together daily has affected my job performance. Basically, being one of the few people that it is still all right to make jokes about, but who can't be myself, pretty much just sucks.

From Brynn Tannehill (pictured at left), a Navy veteran and graduate of Annapolis who is also a transgender woman:

From Brynn Tannehill (pictured at left), a Navy veteran and graduate of Annapolis who is also a transgender woman:

I know that academy leadership has no direct control over the medical policy that bars transgender people from service. But some of the people who are bearing the brunt of this policy are the academy's people, and leaders have a moral obligation to do everything in their power to take care of those under their command; they are charged with training a generation of leaders who do not lie and who maintain the highest ideals of personal honor.

Yet the policy in place forces cadets and midshipmen to lie about who they are, just as DADT forced LGBQ service members to. It forces the friends, allies, and medical personnel surrounding transgender service members into ethical quandaries. It was unethical to put people in such no-win situations when we were talking about gay and lesbian cadets, and it is no more defensible when discussing transgender cadets and midshipmen.

Leaders at the academies possess the influence to quietly push for a better policy that doesn't hurt their troops and force their people into ethically questionable situations. Sidestepping the issue by saying your hands are tied by regulations is only valid when one has no capacity to push for changes to those regulations.

When I was a midshipman, we were taught that taking care of your people is one of the hallmarks of an effective leader. So are being bold and doing the right thing, regardless of the personal cost or popularity.

As a plebe I had to learn inspirational historical quotes such as "I will find a way or make one" and read "A Message to Garcia." Both carried the moral that great leaders make things happen, regardless of circumstances.

I can only hope current academy leaders remember these values when it comes to the silent transgender cadets and midshipmen in their commands.

At left: Members of the graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point stand during graduation ceremonies May 22, 2010, in West Point, N.Y.

At left: Members of the graduating class of the United States Military Academy at West Point stand during graduation ceremonies May 22, 2010, in West Point, N.Y. At left: The midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy march onto the field before a game between the Army Black Knights and the Navy Midshipmen last Saturday at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia.

At left: The midshipmen of the United States Naval Academy march onto the field before a game between the Army Black Knights and the Navy Midshipmen last Saturday at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia. At left: trans former Navy SEAL Kristin Beck.

At left: trans former Navy SEAL Kristin Beck. From Brynn Tannehill (pictured at left), a Navy veteran and graduate of Annapolis who is also a transgender woman:

From Brynn Tannehill (pictured at left), a Navy veteran and graduate of Annapolis who is also a transgender woman:

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes