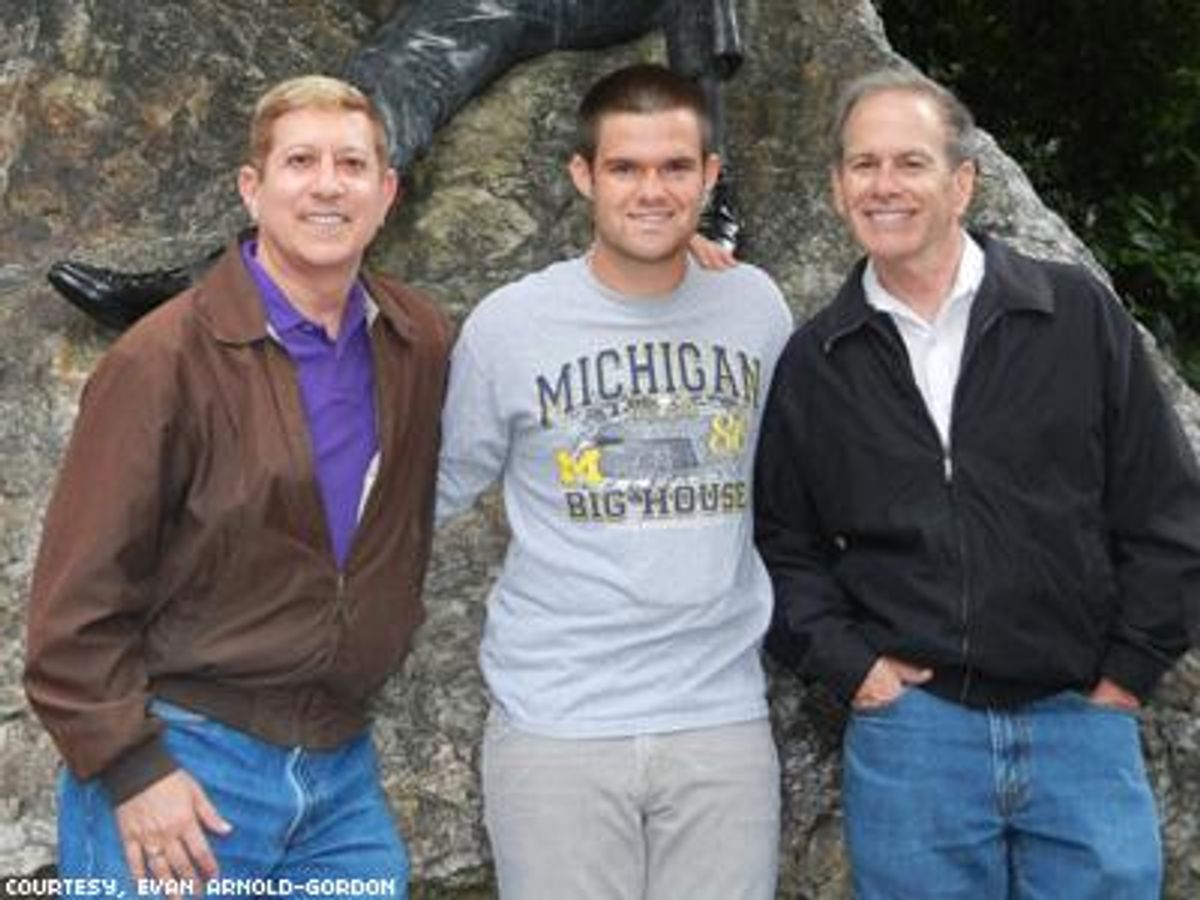

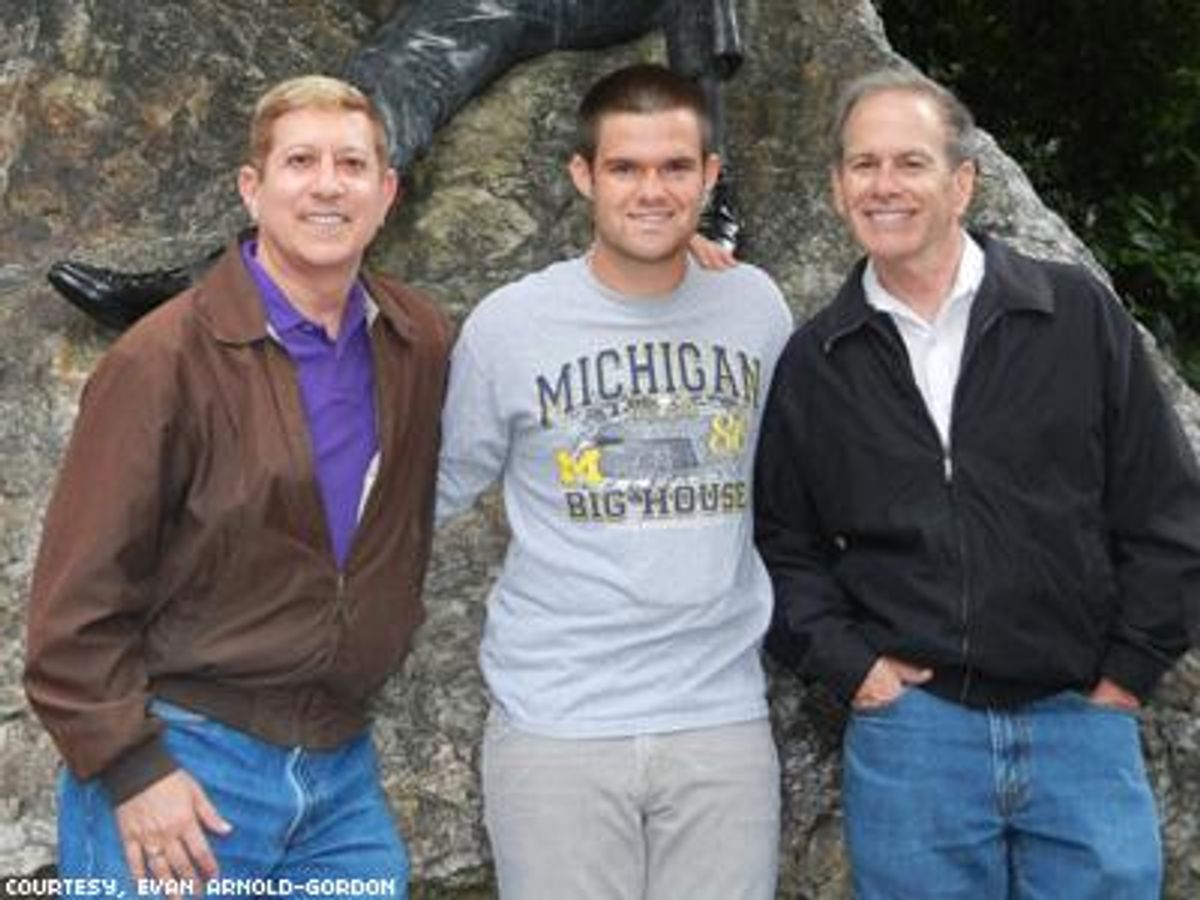

College student Evan Arnold-Gordon knows having a unique parenting set-up isn't necessarily easy, but he wouldn't trade it for anything.

April 30 2014 7:00 AM EST

November 17 2015 5:28 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

I am standing outside the steps of city hall in San Francisco. Jonathan on one side of me, and John on the other. It is August 13, 2009 and after 23 years of a domestic partnership, the state of California is finally recognizing my fathers's marriage. Other gay and lesbian couples are here too, celebrating what they only had dreamed possible. All I can wonder is how could any of these marriages possibly affect the detractors of gay marriage?

And why was I so embarrassed by my alternative family? Why did we have to be so different from the families that come with picture frames?

"That's so gay."

"You're so gay."

"Fucking faggot."

I was in sixth grade when these phrases became common among my classmates. I can still remember going out to recess to play "smear the queer." As I run through the grass field at the back of my school, clutching the football in one hand and holding off oncoming tacklers with the other, I realize the goal of the game is to attack the gay person. I would always play because I love sports, but could never figure out why anyone would want to tackle a gay person.

I had been taught never to use these words by my parents because of the malice they represented. But did everyone else know why I didn't conform to all my other classmates? Going to a Spanish immersion program for elementary school meant there were other diverse kids, either by their religion or race. Somehow that didn't necessarily equate to a completely tolerant social life.

My dads met many years before I was born at a party in San Francisco. My biological father, John, lived in Davis and commuted to Sacramento while my other father Jonathan worked and lived in San Francisco. One of my dad's favorite stories is the three of us walking past a television in the Castro district of San Francisco and me yelling, "Hey, that's Mary Martin!" This flabbergasted the people around us who came up to my dads saying, "What have you done to this poor child?"

Nina, my mother, also lived in Davis and commuted to Sacramento. Eventually, she and John became friends, and their collective relationships led to a three-way decision to have a child. In simply deciding to have a family on their own terms, my parents seemed to be trailblazers -- they went to parenting classes and had to explain their respective parental titles.

Being an only child has its perks. I am my parents' sole pride and joy, after all. However at times it also feels as though I'm a part of a whimsical, comical theatre that has never been rehearsed.

My close friends knew. They had been over to my house, met my dads, my mom, presumably with one of her girlfriends at the time and saw us as an ordinary family. Something was missing however, an empathetic ally who could act as my sibling going through the same trials and tribulations I was going through at school.

My mom had a close lesbian friend who was raising a daughter named Emily with her partner. Then one summer at my Jewish sleep-away camp, I met a boy named Ben who also had two moms. Emily and Ben were my allies, my sympathetic friends I thought of as siblings. They understood the unique act of making two Fathers Day cards, or having different names for each of your dads. It wasn't skin color, or religion we all shared. It was our shared understanding that human beings should not be discriminated against because of who they love. In hindsight I feel sorry for the other kids I grew up with, some of whom came from broken families or troubled households. My family may have been different, but our love for each other was as strong as any other family. The only obstacles we had to overcome were society. And Proposition 8.

Marching in pride parades, or trying to persuade voters to oppose Prop. 8 will always be a responsibility I have. I know that Ben, Emily, and I have a duty to speak for a new generation, especially as the children of gay and lesbian parents.

But in school, I never joined the LGBT clubs for fear of people thinking I was gay. I was always the class clown and jock -- most people knew me, but in actuality, they knew very little about me. I always befriended gay and lesbian students, and still could not come forth with the truth.

I so wanted to tell my LGBT friends that they could come to my parents for advice and support, but I never did. I was afraid that word would spread about my family's situation. The gay jokes would not have stopped, to which my close friends can attest (they say it's a force of habit). But isn't being a bystander the same as bullying? Maybe if I had the same courage my parents had when they came out to their friends and family, I could have spoken up. But I was afraid of how utterly different my family was from all the rest.

I would be lying if I said it has not been difficult. Why couldn't I have a typical set of parents like everyone else? A family I could bring a girl home to and not have to explain how the whole dynamic works. What if I met a close-minded, Republican girl who I really like but who couldn't accept my family?

But to put this in perspective, how ungrateful am I? I could be living in a country, where it is a crime to be gay, let alone a gay couple raising a child. If anything my parents love me too much. They've said before that when they were first realizing who they truly were, raising a son or daughter was practically an unfathomable dream. The older I get, and the more I think about that simple fact, the more I realize I wouldn't trade my life for anyone's in the world.

Burdens can oftentimes end up being a blessing however and in my case, I am extremely blessed. There is a universal truth I learned during the campaigns to allow gay and lesbian couples to get married: If it doesn't affect you at all, why should you give a fuck? I often like to imagine a Twilight Zone episode, where every family has gay parents and saying, "that's so straight," would be the accepted term for "dumb" or "bad."

But then I think to myself, You wouldn't have a story to tell Evan. And there are plenty. One time, a flight attendant bumped my dads and me up to First Class because she "loved our family." And then there was being the only child in the Castro district, and getting as much chocolate as I could eat. And there was the time a couple of years ago, when my dads and I were getting off the subway in San Francisco. As we're about to get off we saw two men, holding hands with their son, no older than 8, standing between them. We immediately smiled at them and as we walked past my dad nodded at me and said to them, "This is what you have to look forward to."

EVAN ARNOLD-GORDON is a junior journalism major at the University of Oregon.