I recently told someone that my mom was a drug addict. "Was it prescription pills?" he asked. Perhaps because so many mothers in the 1970s took what the Rolling Stones made famous in "Mother's Little Helper" (i.e., valium and amphetamines), there's a presumption that because I look white and middle-class, my mother must be a nice old lady who used to dabble in stuff that wasn't illegal and wasn't really drugs.

The truth is, my mother and her friends drank, snorted cocaine, and smoked marijuana. And after she married another addict, she began shooting up heroin. She was an IV drug user, the kind that Americans imagine as dirty, shady, (usually male) criminals who live and die in roach-infested, pay-by-the week motels or crowded urban homeless shelters.

None of those descriptions fit her. Yes, she is a gender-based abuse survivor with enduring mental health issues, but, more importantly, like Philip Seymour Hoffman and River Phoenix before him, my mother is an addict with a brain disease that both causes drug-seeking behavior and, after drug use, literally changes the brain forever. That fried egg commercial with the "This is your brain on drugs" voiceover? It was quite apt; that cautionary tale was about my mother.

There's a distinction we make between drug addicts and us, yet many LGBT people are addicts without even recognizing it, in part because we have a culture built on imbibing. Happy hour socials and circuit parties act as addiction tourism. Yet, how many people at any given Pride festival this summer, drunk or high, would consider themselves addicts? From poppers to booty bumps, drugs were long a part of LGBT culture before our image -- if not the reality of our lives -- was cleaned up for mainstream appeal. "Many people view an addict as someone who doesn't have strong will power or discipline and lacks moral character, but nothing could be farther from the truth," says Joe Putignano, a gay athlete and author of the addiction memoir Acrobaddict. "Addiction is a progressive, chronic disease that if left untreated could be fatal." In his memoir, Putignano vividly describes his decline from healthy, competitive gymnast to homeless heroin addict and back to active performer. "I started drinking, smoking pot, and taking acid and ecstasy while I was competing in gymnastics," he recalls. "I was 17 years old and it was only recreational use at that time. However, the more I experimented with chemicals, the quicker I found a solution to the many challenges I experienced in my life."

One of those challenges was being gay.

"I'm not an addict because I'm gay," Putignano is quick to point out. "However, being gay may have exacerbated my need to blot out negative emotions. Not every gay person experiences this, and many people find different ways to cope with life, gay or straight. Using alcohol and other drugs can instantly and significantly alter moods from sadness to euphoria. Once I discovered how easy and powerful this was, I made a decision to never live without it."

That's one of the drivers of the crystal meth epidemic among gay men, too. It relieves inhibitions, not just in the bedroom (we've all heard about marathon sex-on-meth sessions) but those that come from residual guilt from internalized homophobia left over from childhood. A study from the University of Pittsburgh in the academic journal Addiction put the risk of substance use among LGB youth (trans kids were not included in study) at 190% higher than for heterosexual youth overall -- for bisexual kids and lesbian youth, it was 340% and 400% higher, respectively, than non-queer youth.

But you don't need to be queer to use. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an estimated 23 million Americans age 12 or older use illegal drugs each month, and 15 die every hour due to addiction. For every party monster there is a Hoffman, a nice, respectable, middle-aged professional with a lifelong addiction who died not in front of a bustling nightclub but alone in the silence of his own home.

The day before I sat down to write this, two gay men were found dead of alleged overdoses in New York. Jovin Raethz, a much-beloved 37-year-old trainer from West Hollywood, and Shaun Murphy, 34, were both found, along with GHB and cocaine, in the latter's Chelsea apartment. This came on the heels of new funding allocated by the West Hollywood City Council to raise awareness of the danger of crystal and GHB among the city's gay residents. Gay councilmember John Duran, who championed the cause, told reporters, "Meth will make you lose your teeth and your mind. G[HB] will stop your heart."

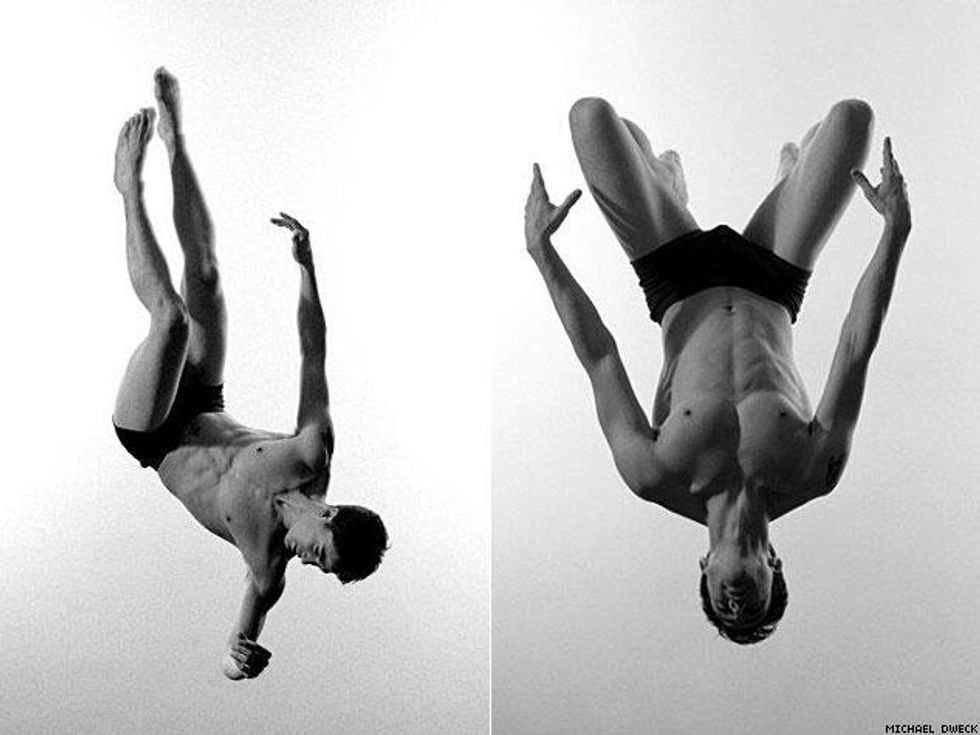

Above: Joe Putignano

By the time Putignano got to college he had already developed an obsession with cocaine, which led to a horrendous prescription drug problem. He was kicked out of college, became violent with his parents, and even wore out his welcome crashing on his dealers' sofa. That's what finally landed him in a homeless shelter. "The strange thing was that I hadn't even started using heroin yet, but by the time I did, I believed I was a 'professional' drug addict and knew how to use without it turning into a problem. This is one of the popular lies we like to tell ourselves: 'I can do this. I'm not as bad as so-and-so. I'll quit tomorrow. I don't have a problem because I don't do it every day' -- and then there's my all-time favorite: 'Just one more time.'"

Hoffman's death dovetailed with a rash of heroin-related deaths in the Northeast. In Pennsylvania, 22 people died after a batch of heroin that was mixed with fentanyl, a narcotic that can be up to 100 times more potent than morphine, hit the streets. For some addicts, learning of the deaths propelled them to seek sobriety; for many more, it led to the oft-repeated mantra "That must have been some really great stuff."

What pushed him to sobriety, says Putignano, wasn't something catastrophic. "What really scared me wasn't dying of addiction, but living with addiction." He felt a constant struggle between being high and attempting to get clean: "I had been trying to get clean from the time I was 19 to 29 years old. I was just throwing punches at a tornado."

When he was 27, the world-class gymnast, who had once trained at the U.S. Olympic Training Center, decided to return to acrobatics. "A therapist in my last rehab gently pushed the idea on me that maybe I could go back to something I had loved as a child, but do it without the restraints of perfectionism and overachieving. In other words, do it because I loved it. This idea burned inside me and while I was in the rehab, I started doing handstands, pushups, and splits. I'm not special, but I can say I worked hard and didn't give up on my dreams."

After his recovery, he joined the cast of Cirque du Soleil's Totem, began studying for a degree in health studies, and started writing his second book. He's become a champion of recovery, appearing on television shows such as Anderson Cooper 360 and CNN's Sanjay Gupta, M.D. as a gay former addict.

Putignano is especially interested in reaching gay and trans users. We're a set of communities that have historically relied on nightlife as the only discrete way to congregate with other LGBT people, and many who have felt what Putignano calls the "soul-crushing feelings of worthlessness, shame, self-hatred, perfectionism, and many other negative emotions" are self-medicating with alcohol and other drugs, even in today's more tolerant America.

But experts like Joseph Sharp, author of Quitting Crystal Meth, agree that drug use is not a moral issue -- and by not recognizing this, we're creating a public health crisis. Meth users, for example, are five times more likely to become HIV-positive than those who don't use drugs. The escalation of meth use is rapid, too: 25% of gay men now use meth, and as much as 70% of users inject the drug rather than smoking or snorting it, increasing their risk for HIV, Hep C, and many other conditions.

And most won't face their addiction and the risky behaviors it causes. "When I was in active addiction, I could not comprehend people who didn't drink alcohol or use other drugs. I thought they were boring, unadventurous, and uptight," Putignano admits.

Today, at book signings, Putignano -- now healthy, fit, and attractive -- is frequently approached by people who want to talk. "The people who approach me are usually friends of addicts or addicts themselves. These people have been touched by pain, and all romantic endeavors take a back seat to this. So while it might be nice to meet my future husband at one of my book signings, it hasn't happened yet." But the point is that with his addiction under control, it might.

My mom has been (mostly) off drugs and alcohol for over two decades, but her mind will never really be her own, and the stigma only adds stress to an already fragile psyche. She is still, simply, an addict, fighting a lifelong battle that many people lose. But what surprises most people is that she has always looked like any other nice, middle-class white lady, and now, at 62, a year after a stroke and a brief hospitalization for psychosis, she's just another senior in her senior village. Is she the only addict there? It's unlikely. One has to wonder if the conversation after Hoffman's death and the new gay tell-alls are part of America finally coming out about addiction. Maybe by holding up the mirror and looking honestly at what we see, some of us will recognize something of ourselves, our friends, our mothers, in these stories and be sufficiently inspired to get the help we need -- or get our loved ones the help they need -- before it's too late.