Even the uninitiated art critic is likely aware of the common use of female bodies as passive subjects in academic, figurative art. Historically, the bodies shown have overwhelmingly belonged to cisgender (nontrans) women.

Throughout modern history, (mostly male) painters from Titian to Cotton have depicted nudes as mythical, allegorical, or, less frequently, as the individual herself. The typical image falls into a tradition called "odalisque" -- images where a female nude is prone and looking off into the distance, her body offered for the eye to consume or appraise.

Such images, at heart, are about physical beauty. The beauty is interconnected with desire, framing the entire tradition within a complex understanding of sexuality, passivity, and personality.

But despite the nude's endurance among classically trained painters like myself, someone is missing: trans women.

Even while contemporary painters such as Jenny Saville have looked at trans bodies, trans women have rarely been seen within artistic traditions as simply women. Women who are interesting people with beautiful bodies worth honoring in paint. Women as the subjects of portraits because of who, not what, they are.

Not that trans women have been entirely absent from art history. Indeed, trans women have been depicted more frequently in the past half century -- but only under the more general category of "gender variance." Over the decades, there's emerged a slew of art that looks at trans people "in general." This can be considered what is known as "third-gendering," which disregards how trans people want to be seen and instead labels them primarily as trans. It is the same as the cultural fascination with intersex subjects, trans or not, which has existed for centuries and often conflated the two.

It's worth noting that art forms besides painting have made efforts to depict trans women, albeit in ways focused on a limited range of gender expressions, as with Andy Warhol's hyperfeminine muse Candy Darling. Meanwhile, photography and film have become broader forms of representation, seemingly expanding simultaneously with clinical options for transition. Within these mediums, pornography has become, in a sense, the "odalisque" of our day. But even in pornography, trans women are a niche, and far too often porn is the first -- or only -- representation a trans girl may see of the woman she could be.

Some of the most impactful art, of course, has come from trans women themselves. In conceptual art, contemporary trans women artists such as Zackary Drucker, Sybil Lamb, Annie Danger, and Juliana Huxtable have made themselves both the subject and object of their own art.

But what of trans women who don't see themselves as artists, who are brilliant and beautiful in their everyday lives, but who do not make themselves into art beyond the daily efforts to avoid misgendering? And what of trans women who do not wish to maintain a highly objectified role in relation to their portrayer, as with Warhol and Darling?

As a classically trained oil painter, I've specifically wondered where trans women have been portrayed within my own medium, and how. I had to ask, Where are the trans women being appreciated in, and through, representational art? I had to conclude that it was up to me to use the skills I had to depict the beauty and diversity of the women I knew.

Since my rather extensive art education did not present me with examples of trans women portrayed in art, it seems most likely that trans women have been inaccurately discussed in art history. I can only imagine how many times a trans woman was incorrectly described as a man dressed in "drag" or someone who was possibly considered "mentally ill," without any validation of their trans status.

Today, it is completely plausible to think that many portraits my professors showed me may, in truth, have been of trans women who were never "read" as such by the artist painting them. This applies to subjects who were seen as "male" as well as those seen as female. Many trans women today, and likely in the past, want nothing more than to be seen as women, without a history of a different gender assignment. So, in some sense, depictions of trans women that haven't "seen" their trans-ness might be considered "successful."

But as with social "colorblindness," such "success" coexisted with persistent mainstream misunderstandings about the realities of trans women's lives. And, of course, as labels change throughout history, there's a good chance many subjects we might consider trans women today would not have self-identified in such terms.

So, where does all this history find today's classically trained oil painter who works on female odalisques? Well, for this painter, it's led to a realization that we artists -- as well as other non-artist LGBT folks as a whole -- need more support in examining the diverse beauty of trans women, especially because trans women face the worst of the violence directed toward sexual and gender minorities.

These days, my art critically engages with feminism's request to see "real," genuine bodies -- bodies not seen solely through male-centric or patriarchal gazes, but through women's eyes. I engage with the feminist call to resist classical painting's preference for uncontroversial models, fully understanding that in reality, some women's bodies were assigned male at birth.

To enact this belief, this year I've begun a series of full-size portraits, entitled Daughters of Mercury, driven by the personalities of their trans female subjects and, in part, inspired by my own love for my close trans female friends. The work includes both nude and clothed subjects, and aims to counter the dizzying, simultaneous desexualization and hypersexualization that society places on trans women's bodies.

My work aims to push back against the social affects that demand women should either explicitly announce their body's trans history to avoid "surprising" others, be considered inherently "undesirable" in the eyes of heterosexual (and sexist) male audiences, or be categorized as automatically "pornographic."

Daughters of Mercury explores more than the passive female and generates admiration based on attributes beyond physical beauty. The series also engages with the history of commissioned and "character" portraiture, which is a genre built on depicting interesting people. Character portraits respect their subject, while operating without the restrictions of having to flatter a client or portray an idealized image.

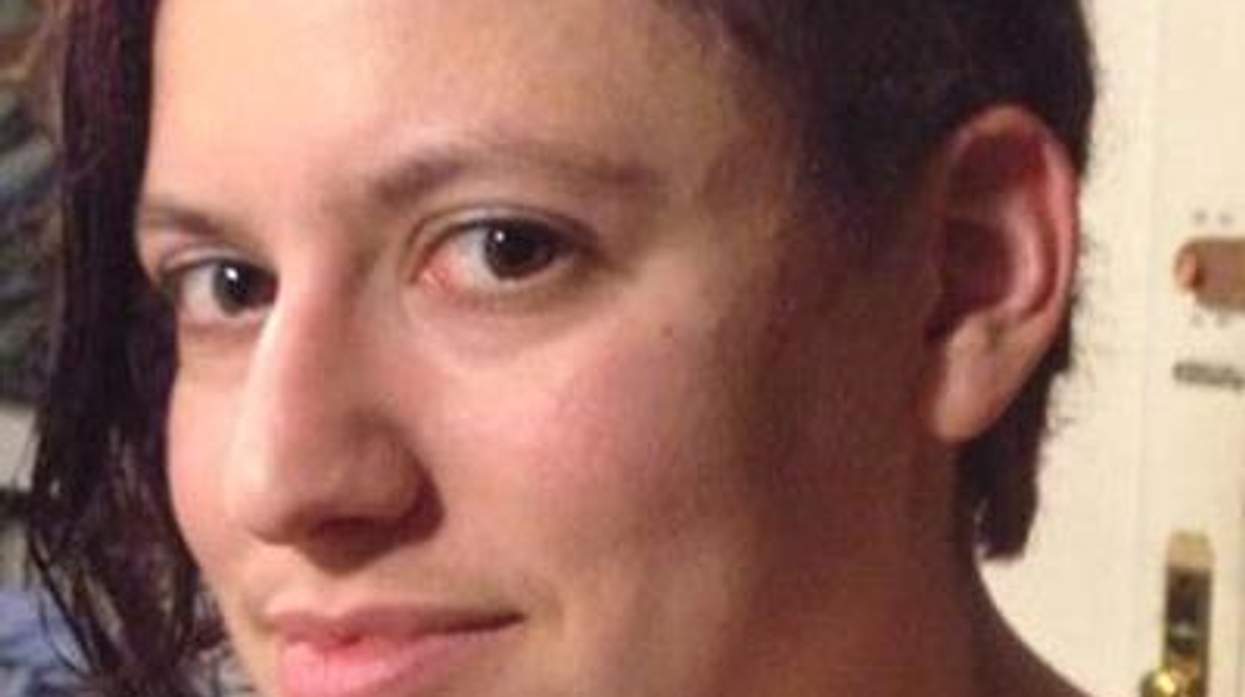

Put simply, I aim to paint trans women as they want to be seen, while exploring the complexity of gender presentation. I hope to challenge viewers' ideas of what women look like, or what they want to look like. Thus far, I've been able to complete one full-scale portrait of Alice (shown above) and have started two others of models Maddie and Red Durkin. I hope to ultimately complete twelve or more, as dozens have offered to sit for the project.

As Daughters moves forward, I dream of painting trans women who are able to commission their own portraits. As women still remain most often underpaid, and trans women especially must often cover the costs of health care surrounding their own transition, most have very little money to spare for art. Thus, I am also fundraising to compensate for materials, travel, and the time of my models and myself. The only way art like this can thrive is if it earns support not just from LGBT people, but from privileged, cisgender straight people like myself, who do have resources to spare.

Creating access and opportunity for marginalized folks to see themselves depicted in art may not be the first action one thinks to take when addressing their privileges -- but I'd argue that it's a more vital one than we often assume. Trans women belong in art and should be able to see themselves in as many artistic mediums as possible, with as much control over how they are being represented as possible.

Then, one day, art students coming up behind me -- an untold number of whom are probably coming to terms with their own gender identitiess -- won't have to scratch their heads and wonder where the portraits of trans women are.

JANET BRUESSELBACH is a New York City-based painter and curator whose color exhibitions have included "I Hate Art" (2011) and "Teleportraiture" (2012). She has painted portraits since puberty and trained further at the Rhode Island School of Design (BFA, Illustration, 2006) and the New York Academy of Art (MFA, Painting, 2009). She likes reading about, playing with, and existing in a futuristic dystopia.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes