Early on Thanksgiving morning, Abuela told me to put the turkey outside. "That's the best way to defreeze it," she said with authority. I put the turkey in a baking pan and placed it in the middle of the backyard terrace where the sun could shine on it all day. And Abuela faithfully followed all my instructions as I translated them to her, without adding any additional ingredients of her own: no Bijol, no garlic, no cumin. By two o'clock the yams were ready for the marshmallow topping and we had finished a pot of Stove Top Stuffing. "?Como? Why? Where?" Abuela asked, as bewildered by the concept of stuffing as I was, despite Jimmy Dawson's explanation, which I parroted to her: "Yes, Abuela, inside. That's why they call it stuffing." We stuffed the bird and put it in the oven alongside Abuela's just-in-case pork shoulder, which she had marinated overnight with bitter orange and garlic mojito.

Wafts of roasting turkey. Wafts of roasting pork. The competing scents battled through the house while I helped Papa and Abuelo set up folding domino tables on both ends of our dining table. We assembled a mishmash of desk chairs, beach chairs, and stools stretching from the kitchen into the living room to seat all twenty-two relatives. I spent the rest of the afternoon making construction paper turkeys like Mrs. Echevarria had taught us in class. I placed one at each setting, then drew pumpkins all over the paper tablecloth and cut into its edges to make a frilly trim. Abuela added a bouquet of gladiolus, which didn't fit the theme but made the table look better, despite the plastic plates and utensils.

"!Ay, Dios mio! Come over here!" Abuela yelled for me. "What is that blue thing?" she asked, alarmed by the pop-up timer in the turkey, which she hadn't noticed before and I had forgotten to point out. "Relax, Abuela. It's nothing. It's supposed to pop when the turkey is cooked," I explained. "Really? Como inventan los americanos. They make everything so easy," she said, relieved, then slid the turkey back into the oven, only to call me over again twenty minutes later. "Bueno, the puerco is done. The turkey must be done too--look at it," she said. "Pero, Abuela, the blue thing hasn't popped up. We can't take it out!" I demanded. "Ay, mi' jo, look at the skin, toasty like the puerco," she insisted, knocking on it with the back of a spoon.

"It's done I tell you. Ademas, it's already seven o'clock. We have to put the other things in the oven before everyone gets here." "Pero, Abuela, we can't," I repeated. She ignored my protest. "What do you know about cooking? Give me los yames and el pie." I knew it was useless to argue any further and hoped for the best as I topped the yams with marshmallows and cinnamon and took the pumpkin pie out of the freezer.

The doorbell rang. "I told you," she said smugly. "Andale--get the door." It was the Espinoza clan who arrived first--all three generations: tia Mirta with her showgirl hips; tio Mauricio wearing a tie and jacket, unwilling to accept that his days as a Cuban tycoon were over; their two children--my cousins--with fancy names: Margot and Adolfo; and their grandmother Esmeralda, who was constantly picking food out of her ill-fitting dentures. They burst through the door with kisses, hellos, and Happy San Givings. Tia Mirta handed Mama a giant pot she brought with her. "Mira, here are the frijoles. I think they are little salty, pero Mauricio was rushing me," she said. Minutes later cousin Maria Elena arrived with her hair in curlers and a Saran-wrapped glass pan full of yuca con mojito. Happy San Giving. Then tio Berto with an open beer in one hand and four loaves of Cuban bread under his armpits. Happy San Giving.

At first I thought it was Abuela who didn't trust that a purely American meal would satisfy. But when she was totally surprised by tia Ofelia's golden caramel flan, I knew it wasn't her; it was Mama who must've asked everyone to bring a dish to sabotage Abuela's first attempt at a real San Giving. My suspicion was confirmed when tia Susana arrived with a platter of fried plantains in a bed of grease-soaked paper towels. "Mira," she said to Mama, handing her the platter, "los platanos that you asked me to bring--I hope they are sweet. Happy San Giving." "Oh, you didn't have to bring nothing, pero gracias anyway," Mama said, casually placing her palm against her cheek, a gesture that always gave her away when she was lying.

Abuela served the pork roast next to the turkey, pop-up timer still buried in the bird. A Cuban side followed every American side being passed from hand to hand. "That sure's a big chicken," tio Pepe chuckled as he carved into the bird and then the pork. "What's this, the innards?" he asked when he reached the stuffing. I had to explain the stuffing concept again to all the relatives as he piled generous portions of turkey and pork on everyone's plates. Papa was about to dig in when I insisted we say grace, proudly announcing I would read a special poem I had written as a prayer in Mrs. Echevarria's class.

Dear God:

Like the Pilgrims and Indians did long ago

we bow our heads and pray so you' ll know

how thankful we are for this feast today,

and for all the blessings you send our way

in this home of the brave and land of the free

where happy we shall forever and ever be.

Amen.

As soon as I finished, tia Susana asked tio Berto, who then asked Minervino, who then asked Maria Elena, who then asked me what the hell I had just said. None of them understood a single word of my prayer in English. "Bueno, ahora en espanol por favor," tio Mauricio requested, and I had to do an impromptu translation of my prayer in Spanish that ended with a resounding Amen and a roar of "!Feliz San Giving! !Que viva Cuba!" from the family. Nothing like the dittos.

And so the moment of truth was at hand, or rather, at mouth, as everyone began eating. Not even a minute later Mama asked, "What's this with canela y merengue on top? So sweet. Are you sure this isn't dessert?" Abuela instantly responded to her spurn: "They are yames, just like yuca but orange and sweet--that's all. Just eat." "Ay, Dios mio--orange yuca! What about blue beans?" Mama laughed, and the rest of the family joined in. "They are not like yuca. They are like boniato. It's what they ate on the first Thanksgiving," I explained. "Really . . . they had march-mellows that long ago?" Mama quipped. She saw my face crumple. "What else do you know about San Giving, mi' jo?" she asked me, changing her tone and taking an interest. I went on for a few minutes, telling the tale of the Pilgrims and Indians in Spanish so that everyone could understand. But soon the conversation changed to tia Mirta's black beans. "You make the best frijoles in all Miami," Papa complimented her, and everyone agreed as they poured ladlefuls of black beans over their mashed potatoes like it was gravy. Nothing like the dittos.

"What's this mierda roja for?" Abuelo asked me, holding a dish with a log of cranberry jelly. I was embarrassed to admit that I hadn't figured out what it was for. "Well, it must be for el pan," Abuelo assumed, and he began spreading cranberry jelly on his slice of Cuban bread, already buttered. "Oh . . . si . . . si." Everyone responded to the solved mystery and followed suit. It was the thing they all seemed to enjoy the most, besides the roasted pork, of course, which tio Berto couldn't stop praising as perfectly seasoned and perfectly tender. He spooned the bottom of the roasting pan and poured pork fat drippings over the lean slices of turkey on his plate. "Ahora si. Much better. Not so dry," he proclaimed after a taste, and then proceeded to drench the platter of carved turkey with ladles of pork fat swimming with sauteed onions and bits of garlic. Nothing like the dittos, but at least after that everyone had seconds of the turkey.

"What's that?" Papa asked when Abuela set the pumpkin pie on the table. "I don't know..." Abuela shrugged and looked to me for an answer. "Pumpkin pie," I said proudly to blank faces at the table. "Calabaza," I translated after realizing I might as well have said supercalifragilisticexpialidocious. "?Calabaza?" tia Mirta shouted incredulously. "Pero that's for eating when you have ulcers and diarrhea, not a dessert. Como inventan los americanos," she chuckled sarcastically. I wanted to smash the pie in her face, but instead I brought the box from the kitchen to show her it was a legitimate dessert. "Poom-quin pee-eh?" tio Regino read out loud, and the entire table burst out laughing. I hadn't realized that pie is exactly how foot is spelled in Spanish. A calabaza foot--that's what was for dessert. Not what I had in mind. "Que va, there must be something else, no?" tio Regino petitioned, and tia Ofelia pranced in showing off her flan and set it on the table. Everyone began oohing and aahing. A creamy custard floating in a pool of caramelized sugar or an ulcer-curing pie? It was no competition.

No one touched the pumpkin foot, except me. I cut a huge slice and dug in. To my surprise, it tasted musty and earthy, just how I imagined the flavor of the color brown would be, though I couldn't admit it. Instead I went on faking my pleasure--"Yum! Delicious"--hoping to tempt others into giving the pie a try. But no one did, except Caco, who could never resist an opportunity to ridicule me. He reached over with his spoon and scooped a chunk off my plate and into his mouth. "Gross! Yuck!" He grimaced and began spitting out the pie. In a flash I reached over to his plate with my spoon and mushed together his chewed-up pie with his slice of flan. We were heading for an all-out food fight, but Mama put an end to it. "!Basta! Enough, it's San Giving Day, por Dios Santo."

After dessert, Abuela made three rounds of Cuban coffee. Tio Berto and Abuelo moved the domino tables into the Florida room and played with Mauricio and Regino, slamming dominos and shots of rum on the table. "What's this, a funeral? Por favor, a little musica, maestro," tio Berto requested, and Papa complied. He turned on the stereo system and put in Hoy como ayer, his favorite eight-track tape with eight billion songs from their days in Cuba. The crescendo began and Minervino took his butter knife and tapped out a matching beat on his beer bottle. Tio Berto grabbed a cheese grater from the kitchen and began scraping it with a spoon, playing it like a guiro. With that, Cousin Danita began one-two- threeing to a conga as she served Cuba libres for the men and creme de menthe for the ladies, her enormous, heart-shaped butt jiggling left and right as if it had a mind of its own. Inspired by her moves and a little too much rum, tio Mauricio took Mirta by the waist and before you could say Happy San Giving, there was a conga line twenty Cubans long circling the domino players around the Florida sunroom.

When the conga finished, the line broke up into couples dancing salsa while I sat sulking on the sofa. You can't teach old Cubans new tricks, I thought, watching the shuffle of their feet. There seemed to be no order to their steps, no discernible pattern to the chaos of their swaying hips and jutting shoulders. And yet there was something absolutely perfect and complete, even beautiful, about them, dancing as easily as they could talk, walk, breathe. "Ven, I'll show you,"

Mama insisted, pulling me by my hand, trying to get me to dance with her. "No, no, Mama, yo no se--I don't know how," I protested. "!Caramba! You're Cuban, aren't you? It's in your blood, mi' jo, you'll see. !Andale! Get up!" she demanded, yanking me off of the sofa and onto the floor. She put her arm around my waist and my hand on her shoulder, leading me through the basic one-two and back. Turn. "More hip, more shoulder," she spoke into my ear while pushing my body left and right. "Yes, like that . . . asi . . . bien . . . muy bien," she complimented me. Acuerdate, even though you were born in Espana, you were made in Cuba--your soul is Cuban," she said, reminding me--yet again--that I was conceived in Cuba seven months before she headed for Spain with me in her womb.

As I began picking up the rhythm, Abuela dashed into the room twirling a dishcloth above her heard and demanding, "!Silencio! !Silencio, por favor!" Papa turned down the music and the crowd froze waiting for her next words. "Tio Rigoberto just called--he said he heard from Ramoncito that my sister Ileana got out--with the whole familia!" she announced, her voice cracking as she wiped her eyes with the dishcloth and continued: "They're in Espana waiting to get las visas. In a month mas o menos, they will be here! !Que emocion! " She didn't need to explain much more. It was a journey they all knew--had all taken just a few years before. A journey I didn't know, having arrived in America when I was only forty-five days old. But over the years I had heard the stories they always told in low voices and with teary eyes, reliving the plane lifting above the streets, the palm trees, the rooftops of their homes and country they might never see again, flying to some part of the world they'd never seen before. One suitcase, packed mostly with photographs and keepsakes; no more than a few dollars in their pocket; and a whole lot of esperanza. That's what the Pilgrims must have felt like, more or less, I imagined. They had left England in search of a new life too, full of hope and courage, a scary journey ahead of them. Maybe my family didn't know anything about turkey or yams or pumpkin pie, but they were a lot more like the Pilgrims than I had realized.

Abuela disappeared and returned with a handful of black-and- white photos of her sister Ileana with the family back in Cuba. "Mira." She explained in detail as she passed each one around, "Here she is on tio Ernesto's old horse at his farm. Here she is in her wedding dress. Here we are by the old sugar mill . . . look, there is the old schoolhouse . . . look, there's the old clock in the park . . . Look how young we all were, remember?" Suddenly, no one, including me, was in Guecheste anymore; they weren't in Miami or Cuba; they weren't in the present, or the future, but floating somewhere in the formless, timeless space of memory. Though I had never met my tia Ileana, it felt as if I too remembered her and the farm, the schoolhouse, the sugar mill. There was more to my past than I had ever realized, a whole other history no book or Mrs. Echevarria ever taught me about: palm trees and mountains; men in straw hats and oxcarts loaded with sugarcane; thatch-roofed homes and red-earth roads in ditto sheets I had never colored.

"Gracias to your San Lazaro!" Mama cried out and rushed to hug Abuela. "I know how much you miss her. Que alegria for you. If only I could get my mother out--soon, soon," Mama insisted. "Happy San Giving a todos!" she cheered. "One day we will all be together." "Happy San Giving!" everyone roared, holding their glasses of sparkling cidra and rum high up in the air. My frustration and disappointment faded. No matter that they called it San Giving, this was my first real Thanksgiving Day. Papa turned the music back on and the celebration continued louder and more exuberant than before. Sprawled on the couch, I fell asleep to the sounds of bongos and tia Susana's cackle; to tio Berto playing the cheese grater and the voice of my tio Minervino, who believed he could sing as well as (if not better than) Julio Iglesias; to the clang of cowbells and beer bottle taps and the soft scuffle of my mother and father dancing a slow danzon.

The next morning Abuela made Pop-Tarts but didn't eat, complaining she had had stomach cramps all night long. She said Abuelo was still in bed, nauseated. Mama admitted she threw up before going to sleep, but thought it was too much creme de menthe. I had diarrhea, I confessed, as did Papa. Caco claimed he was fine. None of us knew what to make of our upset stomachs until tia Esmeralda called. She told Abuela she had been throwing up all night and was only then beginning to feel like herself again. She blamed it on those strange yames.  Then tio Regino called and said he'd had to take a dose of his mother's elixir paregorico, which cured anything and everything; he blamed it on the flan, thinking he remembered it tasting a little sour. The phone rang all day long with relatives complaining about their ailments and offering explanations. Some, like tia Mirta, blamed the cranberry jelly; others blamed the black beans or the yuca that was too garlicky. And some, like me, dared to blame it on the pork. But surprisingly, no one--not even Abuela--blamed the turkey.

Then tio Regino called and said he'd had to take a dose of his mother's elixir paregorico, which cured anything and everything; he blamed it on the flan, thinking he remembered it tasting a little sour. The phone rang all day long with relatives complaining about their ailments and offering explanations. Some, like tia Mirta, blamed the cranberry jelly; others blamed the black beans or the yuca that was too garlicky. And some, like me, dared to blame it on the pork. But surprisingly, no one--not even Abuela--blamed the turkey.

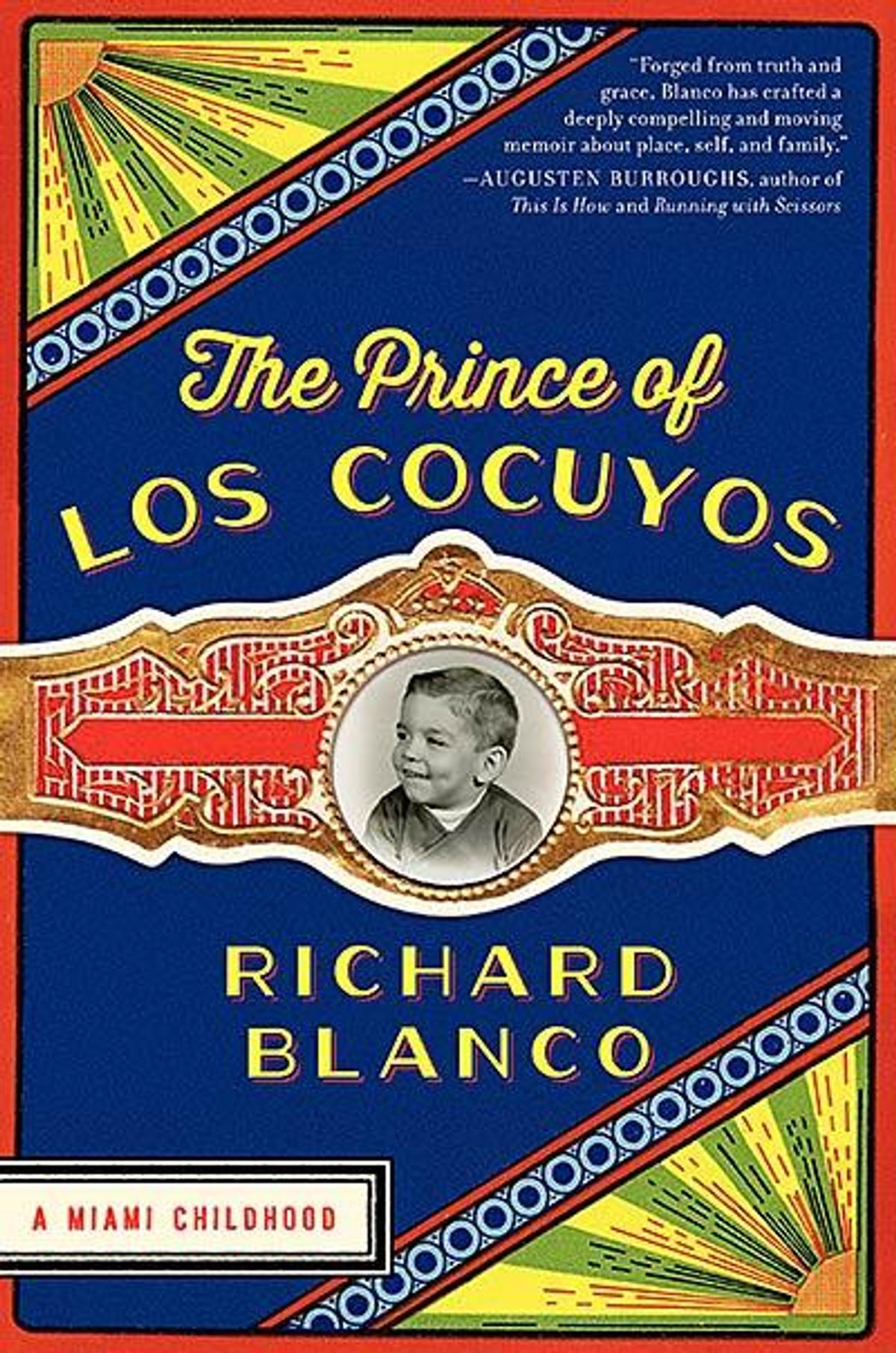

From The Prince of Los Cocuyos by Richard Blanco. Copyright 2014 Richard Blanco. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Then tio Regino called and said he'd had to take a dose of his mother's elixir paregorico, which cured anything and everything; he blamed it on the flan, thinking he remembered it tasting a little sour. The phone rang all day long with relatives complaining about their ailments and offering explanations. Some, like tia Mirta, blamed the cranberry jelly; others blamed the black beans or the yuca that was too garlicky. And some, like me, dared to blame it on the pork. But surprisingly, no one--not even Abuela--blamed the turkey.

Then tio Regino called and said he'd had to take a dose of his mother's elixir paregorico, which cured anything and everything; he blamed it on the flan, thinking he remembered it tasting a little sour. The phone rang all day long with relatives complaining about their ailments and offering explanations. Some, like tia Mirta, blamed the cranberry jelly; others blamed the black beans or the yuca that was too garlicky. And some, like me, dared to blame it on the pork. But surprisingly, no one--not even Abuela--blamed the turkey.

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered