My great-great-great-great grandfather John Sutton owned my great-great-great-great grandmother.

According to the will that John made as he was dying in January of 1846, she was a "mulatto slave" named Lucie, about 45 years old, with eight children and six grandchildren. John Sutton's will left instructions for his 400 cows, four horses, 80 pigs, farm implements and other property to be sold to pay his debts so Lucie and her family could move from Duval County, Fla., to a free state. By December of that same year, John was dead and Lucie's family -- John's family -- had made it up the Mississippi, and settled in Illinois, forever to be free.

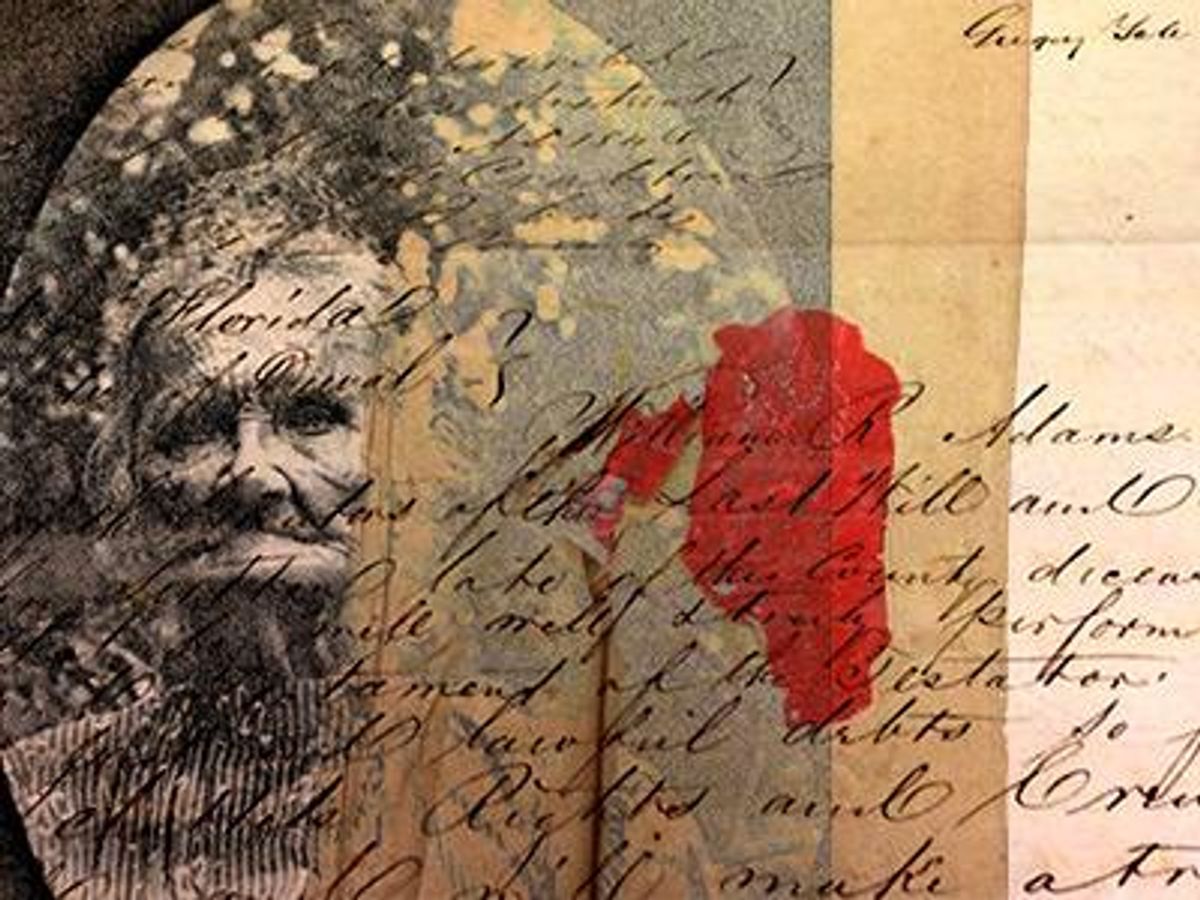

I spent a chunk of time in the last year searching for a copy of the will, which had long been the subject of family lore. I found it. And when I did, I think I also found the answer to a gnawing question: Was it a slave master's rape or something else, like love, perhaps, that created my family? And how does love thrive when society says it's not even supposed to exist?

My lifelong study and knowledge of the brutal history of American slavery, reinforced by recently seeing the horrors depicted in the fil, 12 Years a Slave, heightened my need to know how much rape played a part in John Sutton's legacy. I needed to see the will to know whether John Sutton had a white wife and children in addition to my ancestor Lucie and their children together.

Poring over the sepia handwriting on tea-colored parchment and searching behind the wax seal, still a vibrant scarlet nearly 170 years on, I learned that John had no white wife or other children. And being of sound mind and memory, but "infirm in body," John had taken all the right steps to protect the woman I believe he loved, and their children and grandchildren, from being exposed to the worst dangers that faced blacks in the antebellum South. In response to an article I wrote about my search for the will, I heard from a legal studies professor, Bernie Jones, who told me about a book she'd written called Fathers of Conscience: Mixed Race Inheritance in the Antebellum South. Her book tracked numerous legal cases in which white men, typically widowed or single, left wills giving property or freedom to women of color and their mixed-race children. The wills were often contested by white relatives claiming that the men were mentally incompetent or were unduly influenced by these "jezebels" who used their feminine wiles to take advantage. It was up to the judges' ruling on those contests to decide whether it was more important to follow the terms of the wills or to throw them out since they undermined a society built on the premise that formalized economic and familial relationships between the masters and their slaves were not only distasteful but illegal.

As a gay African-American man, I found the parallels to the modern struggle for marriage equality were inescapable. What happens, I wondered, to love that has no valid, legal way of expressing itself? Without being enshrined in a legally sanctioned relationship, how does love find its way?

I imagined Lucie and her brood, first mourning John, and then packing up all the earthly goods that hadn't been sold to finance the emigration -- caravanning their way from the East Coast across Florida through Alabama and Mississippi and then up the Mississippi River to settle in southern Illinois. Then I thought of committed same-sex couples, before the Supreme Court decisions on Proposition 8 and the Defense of Marriage Act, and in those states where marriage equality is still nonexistent or in doubt, who in similar fashion, but with less risk to life and limb, suffer the psychological and emotional harm of being denied rights because their unions have no legal protection, at least until there is a comprehensive Supreme Court decision or congressional action.

I may be accused of being a traitor to my race, an apologist for slavery, or someone who doesn't appreciate the very real differences between the struggles for racial equality and for gay rights. I certainly don't deny the extreme pernicious evils and abuses of slavery -- or the perversity it imposed on our country's history and its people, the effects of which linger today. Maybe I am romanticizing, or just a romantic. But my Pollyannaish optimism tells me that John and Lucie's tale is a real love story. A story about how love, like water, finds its own path despite obstacles in its way to overcome even the peculiar institution of American slavery. And my heart tells me the same power of love, like a weed pushing up through the sidewalk's cracks, can ultimately overcome the legal barriers and cultural bans on same-sex unions.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella