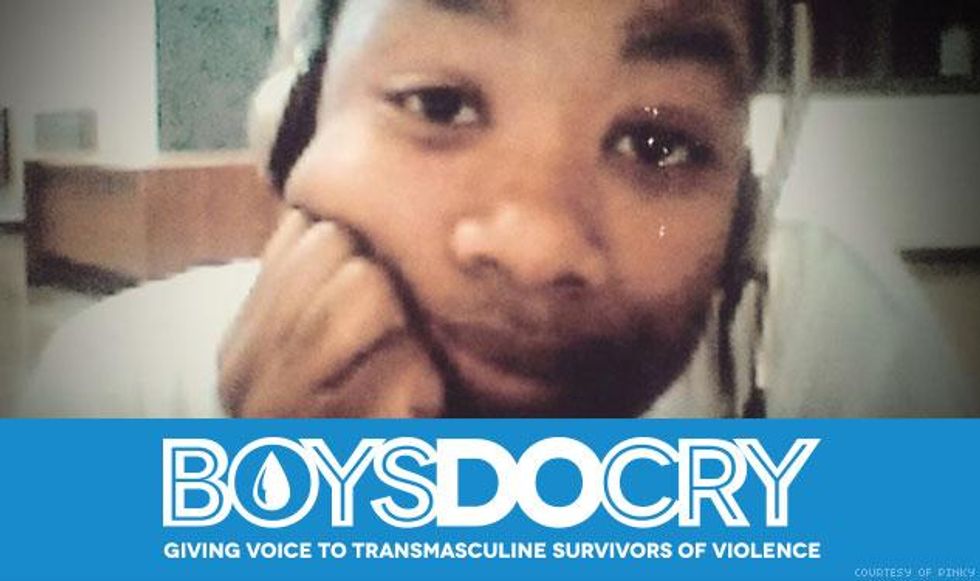

Sexual violence survivor Ky Peterson talks over video chat from Pulaski State Prison in Hawkinsville, Ga.

Sexual violence survivor Ky Peterson talks over video chat from Pulaski State Prison in Hawkinsville, Ga.

There was a time in my life when I considered violence against trans men trivial: too rare, a negligible statistic of little matter to the trans rights movement. And then I became a news reporter.

I'll never forget when I heard about Ky Peterson. When I first got the email about Ky -- a black trans man who's currently serving 20 years in a Georgia prison for killing his rapist in self-defense -- I felt like lightning struck me. I sat up straighter in my chair. The feeling was, in one sense, a reporter's tic: This is a good lead. But for me, it was also something more: This is a story about a trans man I've never heard before.

It's not surprising that I hadn't, it turns out. Now, looking up "violence against trans men" online in preparation for The Advocate's weeklong Boys Do Cry series on the topic, I find that the dearth of such stories is even graver than I imagined.

Consider the phrase's entry on Wikipedia, a common go-to knowledge aggregator: Only one name on the list. Did you guess it? Brandon Teena.

Consider the phrase's entry on Wikipedia, a common go-to knowledge aggregator: Only one name on the list. Did you guess it? Brandon Teena.

So how did I find Ky? Well, I'd first learned about him through a trans man grapevine. I've learned this is the way much of this kind of information gets passed around.

A message from a trans male friend was prefaced by a simple question: "Can you do anything about this?" Yes, yes, I could. I wrote back immediately. "I'll see what I can do." After allowing four months to complete a thorough investigative report on his case, The Advocate published "This Black Trans Man Is In Prison for Killing His Rapist," written by myself and my editor Sunnivie Brydum.

Certainly, I felt proud that I had helped produce the first in-depth story of a transgender man's imprisonment for self-defense anywhere within the U.S. media. But reporting on Ky's case also did something else: It brought me face-to-face with my own blindness to the experiences of trans men that were far different from my own.

Which is, to say, I came face-to-face with my own privileges.

I'm a biracial, white-passing, male-perceived, able-bodied, highly educated trans man who lives in a large, liberal city. I can make ends meet on my income and, though I'm bisexual, I pass as "straight" because I'm married to a woman. I've never been attacked for being transgender. And my violence-free existence has lulled me into unquestioningly perpetuating the simplistic idea that because trans men are men and we live in a patriarchal society that values the male gender above all others, all trans men are always inherently and equally shielded from transphobic violence.

But I can't help but think now that a trans man like Ky would have a very different reaction to that line of thinking (which remains alive and well in parts of LGBT and trans-exclusive communities). Every time we talk, I learn more about how the multiple layers of oppression he faces -- including daily transphobia -- culminate in an existence in which he can rarely feel safe.

As a trans man, his experience is not like mine: Being validated in many queer and trans spaces because my masculinity lends me a certain unspoken authority. In prison, instead, he's hounded by correctional officers who see denial of his masculinity as another way to grind him down.

My experiences and Ky's experiences both represent what it means to be a "trans man" in our 21st-century American patriarchy. So why is the very real violence against trans men like him usually mentioned in trans spaces as an offhand caveat? "Trans men face violence, but trans women face more." Well, mostly (and rightly) because that statement is true.

Of all the reported murders of trans people in the world within recent memory, I can only recall two trans men. There are hundreds upon hundreds of trans women dead because of transphobic violence. Most of them are women of color. Those facts alone have led me to conclude that many conversations about anti-trans violence should center on the oppression faced by trans women and trans feminine people, and especially trans women of color.

But what of the first half of that sentence? I've wondered about this more and more over the past three months since releasing Ky's story. "Trans men face violence." Was that just lip service, knee-jerk and hollow inclusiveness? Was it just an assumption not backed up by empirical reality? Were there trans men speaking out about their experiences of violence, indicating that Ky wasn't just an isolated case?

It turns out there are, here and there. Scrolling through trans-related news stories each day, I encounter one every couple of weeks, largely acts of verbal and emotional violence from families, intimate partners, schools, doctors, police, employers, coworkers, or business establishments refusing to serve trans men. But it wasn't until I met Ky -- albeit virtually, face-to-face in a video call from his prison -- that I started truly labelling this as "violence" in my mind. No caveats, no statements of "yes, but." Just violence, acknowledgeable and valid in its own right.

And then I started hearing from other trans men abused in women's prisons. I started opening my ears and eyes, and spotting little, sometimes coded mentions of violence from trans men who I would then ask privately to share further with me if they were comfortable.

I've now heard from men abused by their parents or by their romantic partners; men being "correctively" raped; men being denied lifesaving health care; men being bullied to the brink of suicide by classmates; men being targeted by police; men being chased out of bathrooms by folks with murderous looks in their eyes; men having objects thrown at them on the street. On and on.

And I've started wondering what more has gone unsaid. For while it's still clear that these experiences are multiplied exponentially for trans women (in large part because of the deadly intersection of transphobia and misogyny), transphobia apparently sometimes also spurs violence against men who don't fit our rigid social definitions of "man." Perceived gender-nonconformity -- especially when a trans man doesn't "pass" all the time as male -- can paint a target on a trans man's back within specific contexts.

And that's the thing. It's all about context. When Ky Peterson's attacker raped him one night on his walk home, he wasn't just raping a trans man -- he was raping a black, non-"passing," rural, working-class trans man. All of these factors influenced the fact that Ky carried a gun with him that night; after all, when he'd been raped once before, he'd learned that Georgia police weren't interested in helping a person like him.

When writer Nicholas Ballou was shot at with a pellet gun from a moving vehicle, he was a teenage fat white small-town trans boy who'd already been verbally harassed for years without adults intervening. When New Yorker Jay Kallio was denied the health care that could have helped with his terminal breast cancer, he was an elder, differently abled, white urban working-class trans man.

Understanding the violence against these men -- violence that has everything to do with them being trans, and not just because they were facing society's all too prevalent trend of male-on-male violence -- cannot be understood outside of their contexts. It cannot be understood outside of the intersections of their multiple identities and marginalizations. And it is worthy of community concern, because it is a direct effect of transphobia.

I don't yet see space in our wider culture, LGBT culture, or trans-exclusive culture to talk much about this. These tales, I find, are mostly passed between trans men in private, as warnings.

But I have hope that the "scarcity myth" shared among many of us trans activists -- that fear that there aren't enough resources to go around for us to focus energy on more than one or two issues at once, necessitating the focus on fatal violence -- is truly just that: a myth. I have to think that our community wants to aid all survivors of transphobic violence or at least listen to their stories without judgment, whether or not they occasionally happen to be male. I believe it's possible, because we have always been a multi-issue community; a community capable of taking on oppression's manifestations in an "and-both," not "either-or" way.

I've personally started down this path by soundly rejecting the notion that because trans men are male, every single one of us must have an abundance of validation and attention heaped on us from the rest of the world, as well as access to means of redress and protection (even though I do). I've started by acknowledging my privileges, and how they aren't experienced evenly by all who share this trans male identifier. Because I know now that this is simply, undeniably untrue.

Trans men of color, as well as working-class, queer, fat, disabled, undocumented, non-"passing," and/or feminine trans men are often not given the specific space and resources needed to heal themselves from violence -- and are, of course, more likely to face violence because of the intersections of the oppressions they face. And I've even encountered men who seemingly have it all -- white, middle-class, physically fit, documented, "passing," masculine men -- who have been targeted solely because they were trans.

So I will never again meet the idea that "trans men face violence" with a dismissive eye roll and a response that implies this must just be more entitled male whining. It would be tantamount to perpetuating an atmosphere that structurally silences survivors who are already silenced in the rest of their lives. I've seen, now, how this needlessly exacerbates hurt when the victims are already experiencing too much damage from the outside, nontrans world. I sincerely believe it's one of the risk factors for the high rate of depression and suicide attempts among trans men. And feeding the silence only restarts a cycle where the absence of stories from trans male victims can be held up as false "proof" that violence against trans men is a nonissue, which then once more leads to men silencing themselves.

Even so, I will always advocate for a focus on violence against trans women, and point out that trans women experience violence at rates that exceed trans men and transmasculine people. I will hold space to talk about violence against trans women without having to mention trans men at all. I will never frame discussions in a way that asks people to ignore violence against women (for that in itself means doing violence).

But sometimes, in just the right contexts, I will now be able to unwaveringly say, "Trans men face transphobic violence." Full stop. And it will absolutely be the right thing to do.

MITCH KELLAWAY is the trans issues correspondent for Advocate.com. His other writing has appeared in the Lambda Literary Review, Original Plumbing, Mic, Mashable, The Huffington Post, and Everyday Feminism. He is the coeditor of Manning Up: Transsexual Men on Finding Brotherhood, Family & Themselves (2014, Transgress Press), an anthology of personal narratives by trans men. Reach him at MitchKellaway.com and @MitchKellaway.

MITCH KELLAWAY is the trans issues correspondent for Advocate.com. His other writing has appeared in the Lambda Literary Review, Original Plumbing, Mic, Mashable, The Huffington Post, and Everyday Feminism. He is the coeditor of Manning Up: Transsexual Men on Finding Brotherhood, Family & Themselves (2014, Transgress Press), an anthology of personal narratives by trans men. Reach him at MitchKellaway.com and @MitchKellaway.

Check back tomorrow to hear more stories in the Boys Do Cry series that pull back the curtain on trans men's experiences with violence.

Sexual violence survivor Ky Peterson talks over video chat from Pulaski State Prison in Hawkinsville, Ga.

Sexual violence survivor Ky Peterson talks over video chat from Pulaski State Prison in Hawkinsville, Ga. Consider the phrase's

Consider the phrase's  MITCH KELLAWAY is the trans issues correspondent for Advocate.com. His other writing has appeared in the Lambda Literary Review, Original Plumbing, Mic, Mashable, The Huffington Post, and Everyday Feminism. He is the coeditor of

MITCH KELLAWAY is the trans issues correspondent for Advocate.com. His other writing has appeared in the Lambda Literary Review, Original Plumbing, Mic, Mashable, The Huffington Post, and Everyday Feminism. He is the coeditor of

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes