On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. stepped to a podium in front of the Lincoln Memorial and delivered his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech to 250,000 people. The March on Washington was the largest demonstration ever held in the U.S. up to that time. It marked a watershed in awakening the nation to the social inequities afflicting African-Americans. Coming on the heels of TV coverage of the savage police brutality against civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Ala., and just a few months before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the nonviolent assembly was also remarkable for its contrast to increasingly urgent calls to armed violence by some groups fighting for equality.

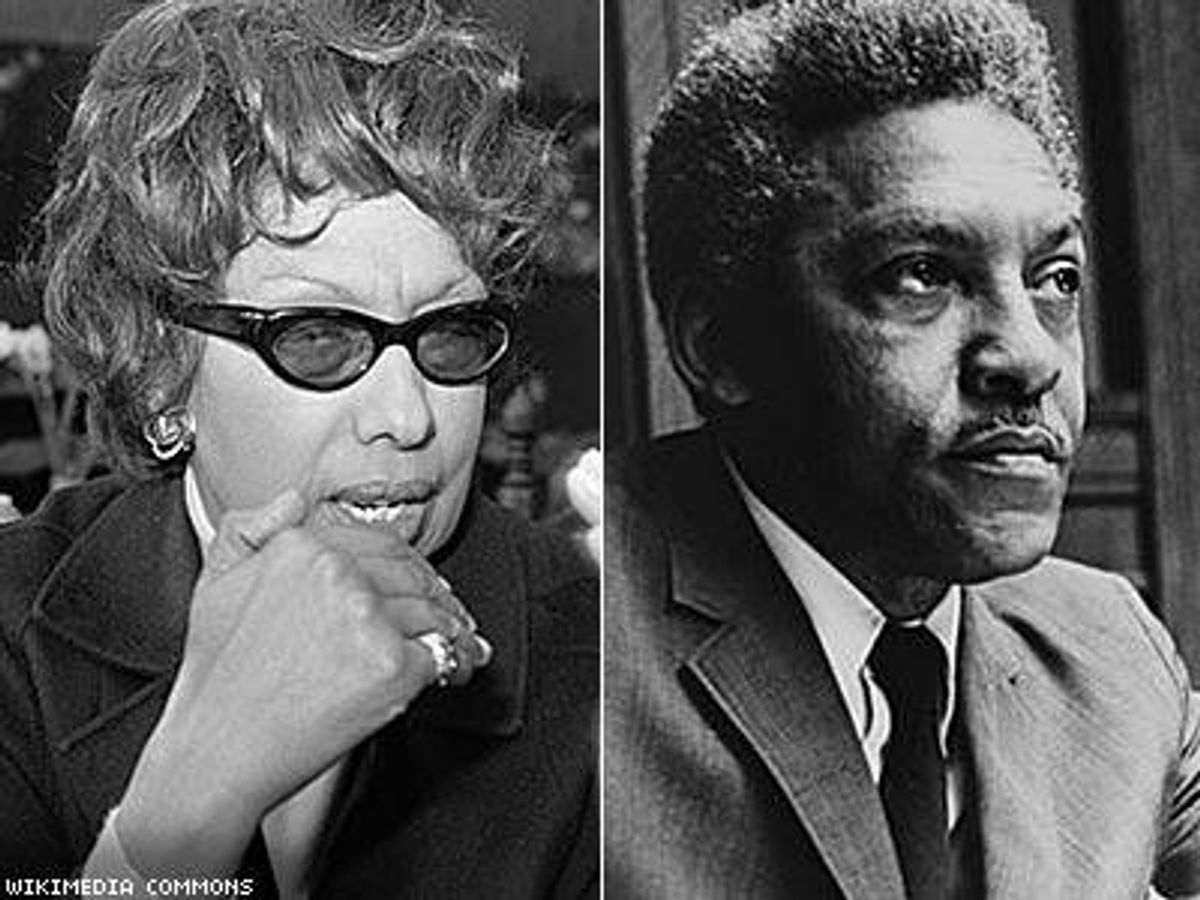

What often goes neglected is the critical part played by a gay man in organizing the rally. Bayard Rustin was the architect of that event but he was also much more. As a Quaker high school student in the 1930s, he protested racial segregation. In 1942, he cofounded the Congress of Racial Equality, an organization based on Gandhi's pacifist principles. During World War II, he was a conscious objector, jailed for refusing to bear arms. After 1955, he served as MLK's adviser on Gandhi's principles of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. Thanks to Rustin's guiding influence and the evolving spirit of the times, King proved successful in organizing the Montgomery bus boycott and the Birmingham march, among other things. As a consequence, by August 1963, the civil rights crusade was in the national spotlight.

Another extraordinary participant in the March on Washington was Josephine Baker, the legendary entertainer and bisexual queen of the Jazz Age. Born in poverty in St. Louis, she went to Paris and became an international sensation, dancing nude or in a belt of bananas, and becoming on of the first black superstars in world history.

During WWII, Baker was a spy for the French. Following the war, she refused to perform for segregated audiences and was responsible for integrating whites-only clubs. By 1963, she'd adopted 12 children of different ethnicities -- raising each according to his/her heritage. Her rainbow family was her way of proving that people could live in harmony, free from the scourge of bigotry. But by 1963, Baker's sequined glamour was out of vogue. Still, she was such a heroine to African-Americans that a group of gay people in Harlem took up a collection to bring "their Josephine" to the U.S., house her at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, as befitted a queen, and see that she attended the rally in D.C. When the great day came, Baker was there -- wearing her army uniform and the medals bestowed on her by France, their highest civilian honors. Still, she had no idea that she'd be invited to address the crowd, one of only two women to do so. But she rallied with customary grace, saying, "You cannot go wrong. The whole world is behind you."

In 1960, Rustin had been hounded out of a visible leadership position because he was gay. King was killed in 1968. The pansexual Baker lived to triumph in spectacular comeback appearances before her death in 1975. But by then, the movement Baker, Rustin, and King had done so much to foster was firmly rooted in the national consciousness, even as Stonewall marked the symbolic start of the modern LGBT revolution -- an outgrowth and continuation, in many ways, of the sheer guts and glory of the civil rights crusade.

In editing The Right Side of History: 100 Years of Radical LGBT Activism, an anthology dedicated with pride to Josephine Baker and Bayard Rustin, I'm honored to place them in the context of other LGBT heroes and heroines, the celebrated and the obscure, who have consistently demonstrated the finest, truest ideals of what it is to be an American.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the telling of the Stonewall riots by Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, the transgender woman of color and national spokesperson for her people, just honored by President Obama with a Lifetime Achievement Award, who was knocked out and jailed after spitting in the face of a policeman. As founder and executive director of the Transgender GenderVariant Intersex Justice Program in Oakland, Calif., and as an activist for transgender people in prison and those stricken by AIDS, Miss Major turned her life into a living embodiment of consciousness, exactly as King counseled. In so doing, by her example, she continues his legacy and serves as an inspiration for many, and not simply those in the transgender community.

But other luminaries chimed in to declare common cause.

As Jonathan Katz, former head of Gay Studies at Yale, states in his foreword in The Right Side of History, the commitment to our founding (revolutionary) principles must be renewed by every generation. As a child of the '60s, a volunteer for King, an antiwar and lifelong gay activist and artist, I'm honored that Evan Wolfson -- "the godfather of marriage equality" -- contributed an essay on that topic. But as he declares, the great task before us remains unfinished; it will continue to unfold until equal legal rights are available to everyone.

As Jonathan Katz, former head of Gay Studies at Yale, states in his foreword in The Right Side of History, the commitment to our founding (revolutionary) principles must be renewed by every generation. As a child of the '60s, a volunteer for King, an antiwar and lifelong gay activist and artist, I'm honored that Evan Wolfson -- "the godfather of marriage equality" -- contributed an essay on that topic. But as he declares, the great task before us remains unfinished; it will continue to unfold until equal legal rights are available to everyone.

What seems self-evident to me is that the great, successive steps in American social progress are not simply distinct; they cross-pollinate. Each affects and helps shape the next phase of our continuing development to "the more perfect union" and greater felicity staked out by our Declaration of Independence and Constitution. For me, personally, that means two things: first, that we stand on the shoulders of gallant forebears -- especially people who put their lives or security at risk when it was dangerous to be "out" or to identify with despised minorities. And second, that we all have a lot more to do as long as bullied LGBT teens are committing suicide in record numbers, and our still-marginalized transgender brothers and sisters face appalling levels of violence and prejudice. Moreover, other tasks remain.

As Tiger Devore, perhaps the most visible spokesperson for intersex folk in the country, declares, we must prevent the genital mutilation of infants or small children to conform to gender norms imposed on them by anyone else and allow them the time to grow and the right to make choices for themselves. But despite our errors and setbacks, the galling disappointments and hard compromise that must be struck in a democracy, the recent Supreme Court decision on marriage equality confirms that we are indeed,on the right side of history. And so, working together and pulling together as Josephine Baker declared on August 28, 1963, we cannot fail.

ADRIAN BROOKS has been engaged in progressive movements for 50 years. In the '60s, he was an anti-ar demonstrator and a volunteer for Martin Luther King Jr. In the '70s, he was one of the first gay liberation poets, and was both scriptwriter and star for the San Francisco Angels of Light theater. His works include the novels The Glass Arcade: Roulette and Black and White and Red All Over; a theater memoir, Flight of Angels; and an anthology on LGBTQI activism, The Right Side of History. He lives in San Francisco.

ADRIAN BROOKS has been engaged in progressive movements for 50 years. In the '60s, he was an anti-ar demonstrator and a volunteer for Martin Luther King Jr. In the '70s, he was one of the first gay liberation poets, and was both scriptwriter and star for the San Francisco Angels of Light theater. His works include the novels The Glass Arcade: Roulette and Black and White and Red All Over; a theater memoir, Flight of Angels; and an anthology on LGBTQI activism, The Right Side of History. He lives in San Francisco.

As Jonathan Katz, former head of Gay Studies at Yale, states in his foreword in The Right Side of History, the commitment to our founding (revolutionary) principles must be renewed by every generation. As a child of the '60s, a volunteer for King, an antiwar and lifelong gay activist and artist, I'm honored that Evan Wolfson -- "the godfather of marriage equality" -- contributed an essay on that topic. But as he declares, the great task before us remains unfinished; it will continue to unfold until equal legal rights are available to everyone.

As Jonathan Katz, former head of Gay Studies at Yale, states in his foreword in The Right Side of History, the commitment to our founding (revolutionary) principles must be renewed by every generation. As a child of the '60s, a volunteer for King, an antiwar and lifelong gay activist and artist, I'm honored that Evan Wolfson -- "the godfather of marriage equality" -- contributed an essay on that topic. But as he declares, the great task before us remains unfinished; it will continue to unfold until equal legal rights are available to everyone. ADRIAN BROOKS has been engaged in progressive movements for 50 years. In the '60s, he was an anti-ar demonstrator and a volunteer for Martin Luther King Jr. In the '70s, he was one of the first gay liberation poets, and was both scriptwriter and star for the San Francisco Angels of Light theater. His works include the novels The Glass Arcade: Roulette and Black and White and Red All Over; a theater memoir, Flight of Angels; and an anthology on LGBTQI activism, The Right Side of History. He lives in San Francisco.

ADRIAN BROOKS has been engaged in progressive movements for 50 years. In the '60s, he was an anti-ar demonstrator and a volunteer for Martin Luther King Jr. In the '70s, he was one of the first gay liberation poets, and was both scriptwriter and star for the San Francisco Angels of Light theater. His works include the novels The Glass Arcade: Roulette and Black and White and Red All Over; a theater memoir, Flight of Angels; and an anthology on LGBTQI activism, The Right Side of History. He lives in San Francisco.