Houston voters recently overturned HERO, the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance, which sought to create protections against discrimination based on 15 characteristics, including sexual orientation and gender identity. In the weeks leading up the election, the campaign to overturn the proposition focused on a deep fear in American culture: a sexual menace in the form of transgender people, who might use the private space of a bathroom to assault women and children.

It was a masterful manipulation of rhetoric. The opposition to HERO, led by the Campaign for Houston, turned the language of civil rights on its head, transforming HERO into a free pass for sexual predators.

The metaphor of sexual predation and contamination has long been a mainstay in American political speech. Earlier in our history, similar resistance to equal rights protection was directed at African-Americans, playing on the same fears. The opposition to civil rights in 2015 effectively employed the language of 19th-century racism to advocate for homophobia and transphobia in the 21st century.

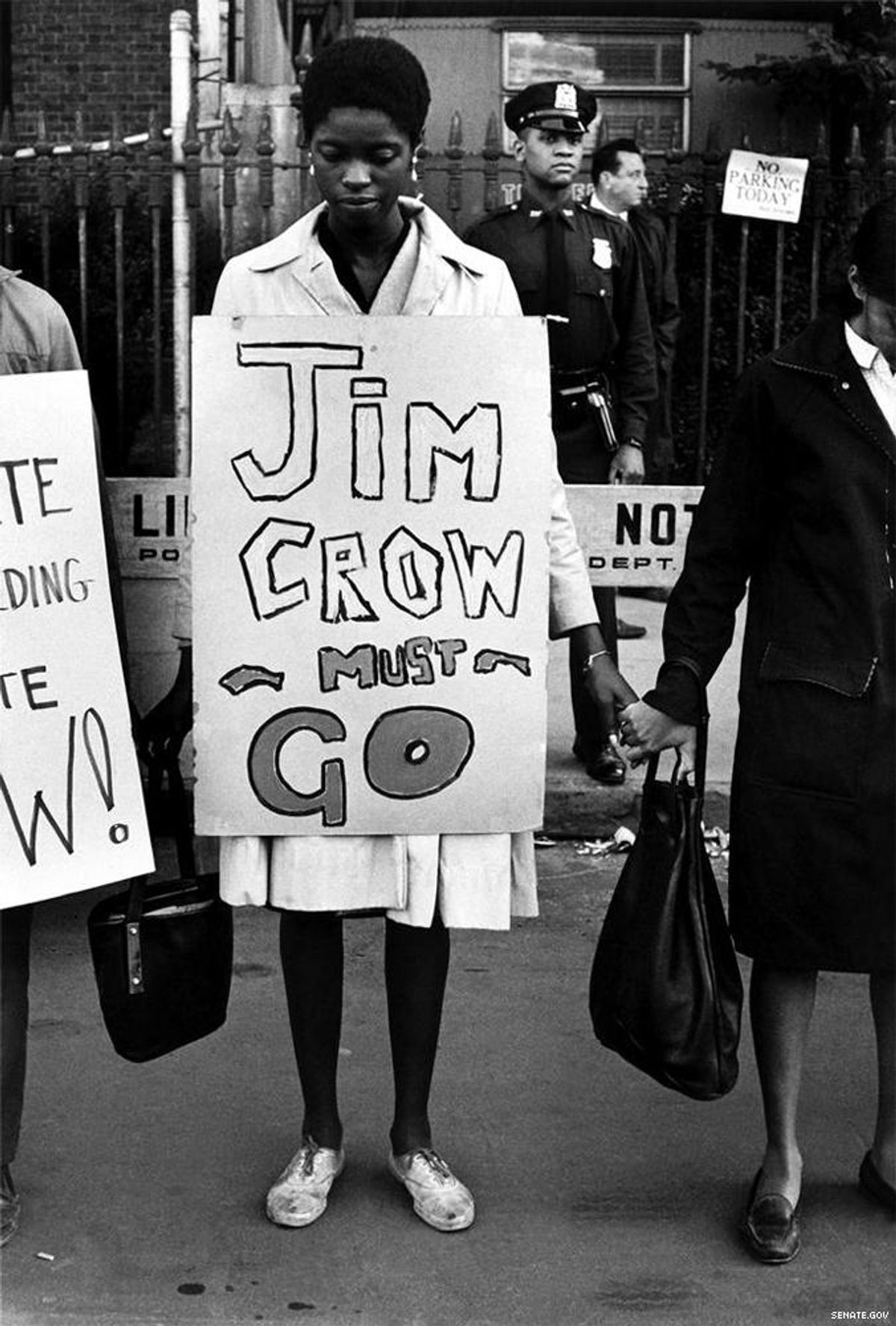

The fear of a sexual menace is deeply rooted in American history and culture. Jim Crow rhetoric held that African-Americans were sexual predators and that unfettered African-American liberty would put white women and children at risk. George T. Winston, president of North Carolina A&M (now North Carolina State University), wrote in 1901 that the Confederacy's defeat in the Civil War inevitably led to the unprotected "Southern woman with her helpless children [who] shudders with nameless horror. The Black brute is lurking in the dark, a monstrous beast, crazed with lust." In Thomas Dixon's The Clansman, the 1905 novel on which the movie The Birth of A Nation is based, Gus, the black villain, crept outside his former master's window waiting for his prey, his former mistress Marion, to appear. When he cornered her alone in the bedroom, he raped her -- "the black claws of the beast sank into the soft white throat and she was still."

Upon closer inspection, however, the urgency to rein in the black sexual menace was, at its core, centered on overturning civil rights measures that upheld equal protections to African-Americans. In the disastrous Plessy decision of 1896, the Supreme Court ruled the Fourteenth Amendment did not guarantee African-Americans social equality with whites, and therefore, states could prohibit African-Americans from entering the protected white space of a first class railroad car. Yet again, a massive, disingenuous resistance to civil rights, based on the premise that women and children needed protection against black sexual harassment, facilitated the segregation of African-Americans.

Throughout the 20th century, racist language in state and local laws warned of a creeping sexual threat by way of integrated bathrooms and of imminent sexual assault of whites by predatory African-Americans hiding in private spaces. Consider an Alabama law prohibiting the entrance of African-Americans into hospital rooms where a white woman is already present: "No person or corporation shall require any white female nurse to nurse in wards or rooms in hospitals, either public or private, in which negro men are placed." And a Georgia law prohibiting interracial barbering: "No colored barber shall serve as a barber [to] white women or girls." And an Oklahoma law banning racially integrated bathroom in mining: "The baths and lockers for the negroes shall be separate from the white race, but may be in the same building." During World War II, Theodore Bilbo, two-time governor of Mississippi and member of the Ku Klux Klan, blamed President Franklin Roosevelt for introducing racial contamination at the federal level. Roosevelt convened the Fair Employment Practices Committee, which compelled the equal protection of whites and African-Americans in defense contracts. Bilbo claimed his office received "hundreds of complaints from white girls who are now forced to stand and wait patiently until the odiferous females of the Negro race have finished their toilets in closets formerly used and occupied by whites girls only."

The Campaign for Houston echoed this bilious language, particularly when it came to transgender sexual predation. The resistance spoke of "men in dresses" lying in wait, poised to prey on unsuspecting women and children. Lt. Governor Dan Patrick said that HERO was "about allowing men to enter women's restrooms and locker rooms - defying common sense and common decency." In an anti-HERO radio ad, "Rashinque,"a resident of Houston was concerned that "a man can be there, right next to me while I'm getting undressed in the locker room at the gym. That is dangerous. That is filthy. Guess what? This woman and the majority of women around Houston view this as an invasion of privacy, a threat to our safety." Yet another racial dog-whistle.

The TV ads produced by the Campaign for Houston were even more graphic. One TV spot warned that any man "claiming to be a woman that day" could enter a public bathroom unrestricted and no one would be able to stop them. Behind the bold text, a faceless man first hovers outside a bathroom, then follows a frightened young white girl into a stall. A second ad, which drew directly on the infamous 1988 Willie Horton Bush presidential ad, first showed the mayor of Houston, Annise Parker, declaring sexual assault in bathrooms "just doesn't happen!" and replayed it three times. Then, it turned to Paula Witherspoon, a transgender woman and a convicted sex offender (25 years ago), who was ticketed for disorderly conduct at a Dallas hospital after she "told police that he should be allowed into women's and girls' facilities because he now felt that he was a woman." Another member of the HERO opposition produced a video that featured a communication from a supposed supporter of HERO, who could not wait "for HERO to pass so he can dress up like a woman and follow you around and rape you in bathrooms."

This imaginary threat by transgender menace has produced real and troubling violence. This is why the linguistic parallels are so important. In 2015, almost 25 transgender Americans, nearly all of them black and brown, have been murdered, and in most of the crimes, the perpetrator has not been found. One hundred years ago, African-American organizations would have called these lynchings. By linking the black menace to a transgender menace, and a black contamination to a transgender contamination, the people most vulnerable to sexual assault and murder were the ones most often accused of potential future violence.

The statistics show that transgender Americans are victimized by hate crimes at a greater rate than nearly every other population in the United States. Unfortunately, statistics alone cannot undo the visceral fear of sexual predation. Instead, changing minds involves showing the humanity of transgender Americans. They are our brothers and sisters, and their rights as Americans must be protected. The Campaign for Houston spent nearly $2 million convincing Houston voters that transgender Americans are immoral, uncivilized, unsafe, and unclean. The Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia asks us to consider the warning of Thomas Nelson Page, who wrote in 1901 that African-Americans were "lazy, thriftless, intemperate, insolent, dishonest, and without the most rudimentary elements of morality." While guaranteeing civil rights is still a work in progress, the first order of business, in Houston and elsewhere, is reaffirming the humanity of transgender Americans, gay and lesbian Americans, and the 13 other categories of people protected by HERO.

NIKKI BROWN is associate professor of history at the University of New Orleans and a fellow and visiting professor at the James Weldon Johnson Insitute for the Study of Race and Difference at Atlanta's Emory University.