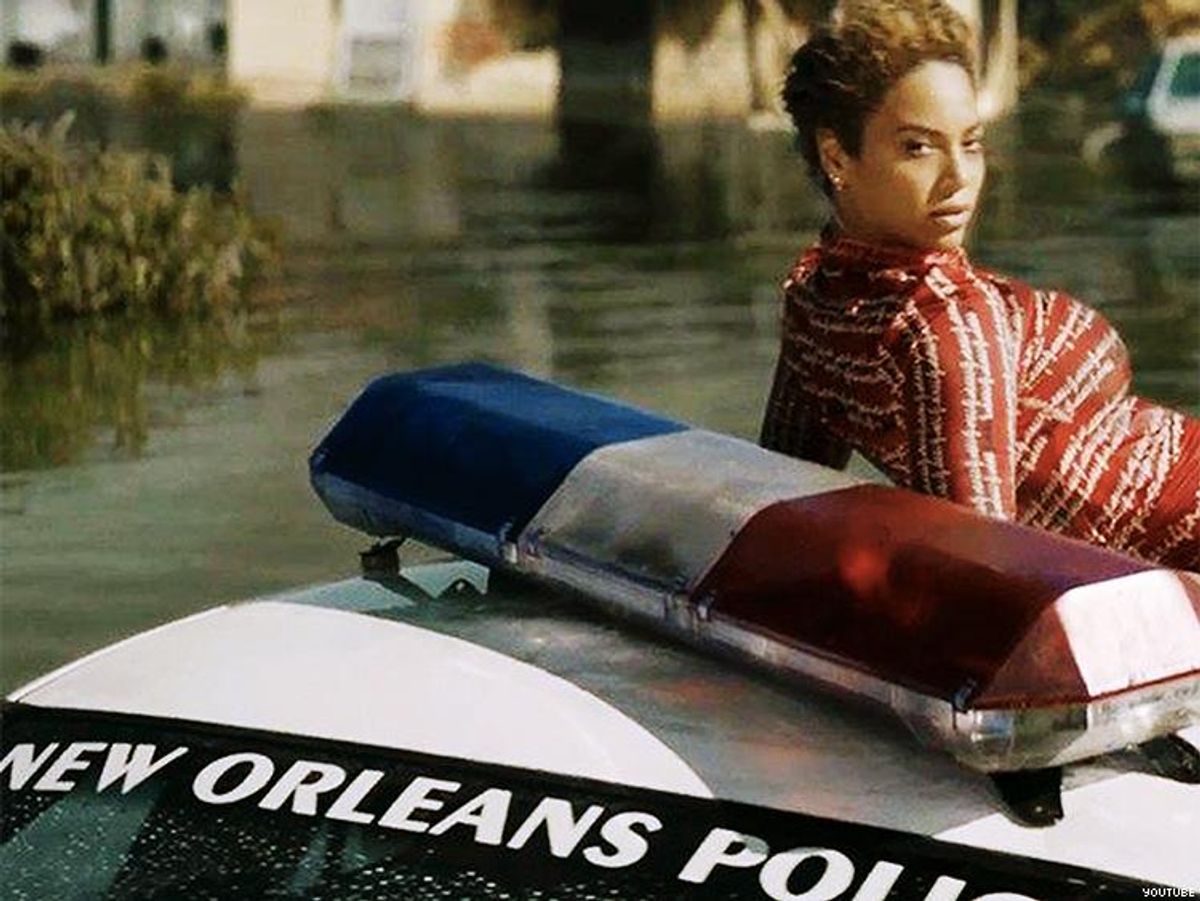

Beyonce's new song "Formation," released over the weekend and performed at Super Bowl 50, is a masterpiece of black protest art and social commentary.

Using footage from the 2013 New Orleans documentary That B.E.A.T as its backdrop, "Formation" is both a personal and political statement about repression and a celebration of black life in America.

As a splendid videographic gumbo of New Orleans's inimitable multiple identities of southern blackness told from Queen Bey's perspective, we see black women front and center -- from sisters with Afros in stylized Black Panther outfits to the several archetypical Southern black women Beyonce morphs into.

As a meditation on the intersections of place, class, and gender identity, past and present, "Formation" is also unashamedly queer. That queerness is front and center -- from its signature hypersexual "ass-shaking" gender-bending hip-hop music and dance form (reminiscent of 'Bama's Prancing Elites), appropriation of gay expressions, to the words of local hero Messy Mya and the genderqueer local voice of royal "Queen of Bounce" diva Big Freedia, who's heard speaking in the song.

"It was a total shocker when I got a call from Beyonce's publicist and she said Beyonce wanted me to get on this track," Freedia told Fuse, which airs her reality show. "When I heard the track and the concept behind it, which was Beyonce paying homage to her roots [New Iberia, La.], I was even more excited! It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life and I was beyond honored to work with the original Queen B. I think it turned out amazing too!"

According to Zandria Robinson of the New South Negress site, when "the voices and presence of genderqueer folks enter to take over [in 'Formation'] ... they, in fact, ask us the toughest questions," about racism, police brutality, and power.

At the song's 1:10-minute mark, Big Freedia, in a her thick N'awlins accent, shouts out authoritatively, "I came to slay, bitch." "Slay" is a term coined by the African-American LGBTQ community, meaning to dominate, conquer, or take care of business.

In "Formation," Beyonce unquestionably honors the inimitable black queer culture of New Orleans -- a singular look and feeling that's often either misunderstood or underrepresented in popular art. And Bounce music, in particular, has been around since the early 1990s but only recently celebrated.

While a lot of NOLA's gay bars and enclaves escaped devastation by Katrina, many of the city's African-American queers are not patrons of its white gay bars or residents in those gilded communities. But the race and class segregation between New Orleans's African-American and white LGBTQ residents cannot take away from their rich contributions and expressions.

The city has a long musical tradition of gay and cross-dressing performers that have been an integral part of the musical culture, from the inception of Mardi Gras balls and krewes to its infamous annual Southern Decadence festival.

Openly gay African American cross-dressing male rappers might sound dissonant and come across as an oxymoron, but they're merely part and parcel of a long New Orleans tradition.

"As far back as the '40s and '50s, it was a really popular thing," NOLA musician Alison Fensterstock told The New York Times.

"Gay performers have been celebrated forever in New Orleans black culture. Not to mention that in New Orleans there's the tradition of masking, mummers, carnival, all the weird identity inversion. There's just something in the culture that's a lot more lax about gender identity and fanciness. I don't want to say that the black community in New Orleans is much more accepting of the average, run-of-the-mill gay Joe. But they're definitely much more accepting of gay people who get up and perform their gayness on a stage."

That's why their inclusion in Beyonce's "Formation" was not a stretch, but a shout-out.

Rev. Irene Monroe is a writer, speaker, and theologian living in Cambridge, Mass.