CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Is porn responsible for gay men's Adonis-like body standards? A log cabin, in the mountains of Aspen. Two men walk in. One has strikingly blond locks -- a touch away from sheer white. The other also has blond hair, but a little darker and more common. After making what amount to furtive excuses -- porn scripts in the '80s being what they are -- the two men start to kiss, etc, etc.

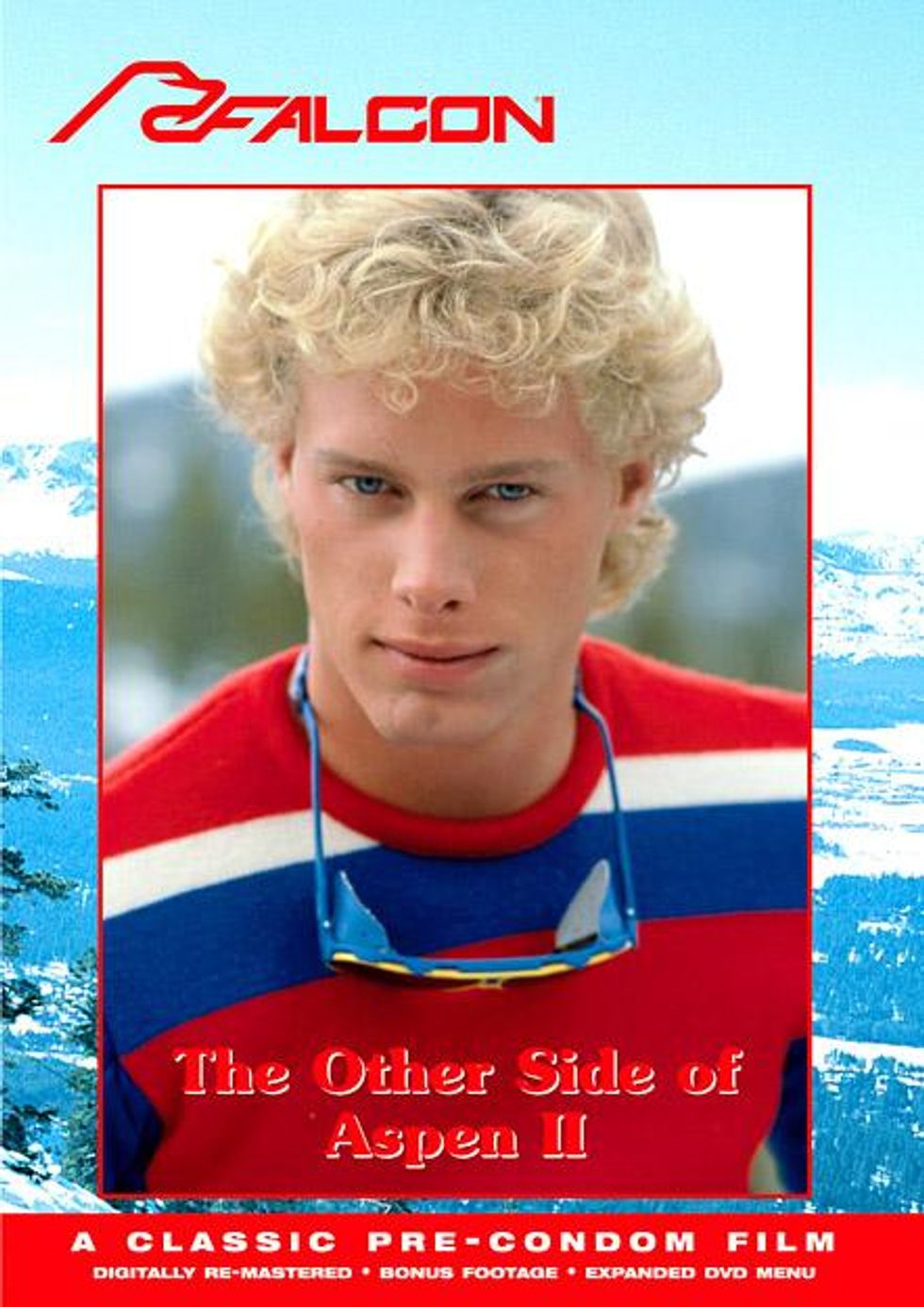

It's a scene from Falcon Studios' classic porn film The Other Side of Aspen II. The idea of a feature-length film was a revelation in the porn industry. It made Falcon Studios a fortune and created a number of imitator studios. The VHS tape helped it to become popular because it could store that much film, but the success of The Other Side of Aspen II wasn't really in VHS or Falcon Studios being an already reputable brand. It was in the men.

Besides the porn film, "the boy" was also an innovation of Falcon Studios -- specifically, of its earnest Midwestern founder, Chuck Holmes. He happened upon the formula for the perfect man, at least in porn, according to interviews in last year's documentary, Seed Money: The Chuck Holmes Story. As soon as he found it, he stuck to the formula: blond feathery hair frozen with hair spray, hairless body, rock-hard abs. This was was Holmes's Adonis. We still live with it today.

The credit doesn't all go to Holmes. Just before the Adonis started appearing in his films, another gay entrepreneur, Calvin Klein, had launched an iconic advertising campaign that sexualized the nubile man, though obviously not as explicitly as Holmes later did. According to a testimony from Holmes's business partner and lover, Steven Scarborough, the porn king was so inspired by the Calvin Klein models' beauty he created a mold out of it, into which he poured all his future talent.

Perhaps predictably, Holmes's story is a tragic one. The AIDS crisis devastated his studio as well as his cast. Kurt Marshall, the silver-haired youth from the video, died at age 22. Holmes didn't win allies because he insisted for a long time on not using condoms in his films. After the crisis grew a touch less dire, Holmes attempted to invest in political causes but found his money wasn't welcome; he died of AIDS-related causes in September 2000. A debate raged posthumously over whether to name a building at the San Francisco LGBT Community Center after him, which advocates eventually won. Outside of San Francisco, however, he is almost forgotten. The new film is the first attempt to revive his memory.

While his memory is not secure, his legacy is. Outside of the bear subculture, the hairless Adonis is the highest possible ambition of a boy who wants to be beautiful. Porn today is still ruled by it -- though there is a move away from shaving pubic hair -- and Pride, a celebration of, among other things, sexual liberation, manifests as a parade of the very same Adonis that Holmes and Klein helped create.

The same type of beauty is accepted by straight people, as well. The "metrosexual" look of the 1990s and 2000s included heterosexual men reaching for the same groomed, slightly androgynous look that Holmes glamorized. I can remember being affected by the nubile form. I came out in the northeast of Scotland, where my exposure to gay culture was very limited: I had no gay friends, and therefore to fit in as a "gay" -- which is all I wanted -- I took my cues from TV, like Queer as Folk. I camped it up and made up stories about salacious flings. I also, inadvisedly, obsessively shaved my body -- including my forearms. My sisters, who are not strangers to the pressures of looking fashionably shorn, were merciless to me.

The Adonis, apart from being the cause of no doubt countless poor grooming decisions, is also a very classical beauty form. Marshall, the boy from The Other Side II, is a dead ringer for Michelangelo's David. His hair is curled like his, the body is the same -- though rather shorter -- and is smooth like his, and white like marble. While this may not be surprising at first, it is when you consider the gay culture out of which the Adonis came. At the time, gay men were rebelling against the challenge from outside we were all a bunch of "fairies." The "masc," with his boots, beard, and plaid, gained enormous currency, which both parodied and fetishised the so-called real men of America. Klein and Holmes made themselves voluntary exiles from this, crafting a classical Grecian beauty for gay men to aspire to and hone themselves toward.

Today, constrictive ideas about female beauty are fiercely challenged. The same should go for male beauty. There have already been plenty of challenges to the Adonis's appeal, whether or not we call it that. Much of this comes from men, including myself, who prefer natural-looking men, who might say the Adonis should be cast in marble only and not the de facto bodily aspiration for gay men. Even with my preference, however, I can't say that the steel-like perfection of Holmes's boys doesn't hold an irresistible appeal; I can challenge it, but I won't deny it. As with Michelangelo's David, it's satisfying and enraging to admire it, want it, and never have it.

I'm unsure about the good or evil of Holmes's legacy. The striking beauty of other men is something I draw a lot of the previously mentioned rage and satisfaction from. Yet I have suffered terrible angst in abortive attempts to achieve it, and others still do. Worse, perhaps, some accept a sort-of half-life as the kind of men who won't ever achieve anything as sexual beings. Holmes's contribution has not made me happier, but it has made me hornier -- and, perhaps perversely, there are plenty of times I'd rather be the latter than the former.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

Is Texas using driver's license data to track transgender residents?

December 15 2025 6:46 PM

Rachel Maddow on standing up to government lies and her Walter Cronkite Award

December 15 2025 3:53 PM

Beloved gay 'General Hospital' star Anthony Geary dies at age 78

December 15 2025 2:07 PM

Rob Reiner deserves a place in queer TV history for Mike 'Meathead' Stivic in 'All in the Family'

December 15 2025 1:30 PM

Culver City elects first out gay mayor — and Elphaba helped celebrate

December 15 2025 1:08 PM

Texas city cancels 2026 Pride after local council rescinds LGBTQ+ protections

December 15 2025 12:55 PM

North Carolina county dissolves library board for refusing to toss book about a trans kid

December 15 2025 11:45 AM

Florida and Texas launch 'legal attack' in push to restrict abortion medication nationally

December 15 2025 11:18 AM

No, Crumbl is not Crumbl-ing, gay CEO Sawyer Hemsley says

December 15 2025 10:12 AM

11 times Donald Trump has randomly brought up his ‘transgender for everybody’ obsession

December 15 2025 9:22 AM

The story queer survivors aren't allowed to tell

December 15 2025 6:00 AM

Rob Reiner, filmmaker and marriage equality advocate, and wife Michele dead in apparent homicide

December 15 2025 1:08 AM

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes