The evening of May 3, 1991, was one which the members of the Gay and Lesbian Youth Group of South Florida had spent weeks waiting for. Club 21, a gay nightclub in the town of Pembroke Park, had agreed to host an evening of dancing and celebration for the members of the youth group. As many of our members were under 21, special accommodations were made to ensure that alcohol would only be served to those of legal age, and the youth group's leaders were on hand to assure that everyone enjoyed a safe evening.

The night began well, and the event was running smoothly until shortly before midnight, when dozens of deputies from the Broward Sheriff's Office burst into the club, many wearing masks, and began yelling at the guests, grabbing them, and shoving them down onto the dance floor. Between the yelling by the police, you could hear several of the young people crying in fear, afraid of whatever the police were about to do.

As leader of the youth group, I asked to speak with whoever was responsible for the sheriff's team. I was simply told that if I said another word, I would be charged with resisting arrest. I went ahead and asked why we were being detained and if we were under arrest. While the sheriff's officers refused to answer those questions, the fact is that we were being detained on the floor and were not allowed to leave. While the sheriff later claimed that only six people were arrested, the truth is that hundreds were.

After an exhaustive search of the venue, several of the sheriff's officers set up tables to operate from. One by one, each person there was interrogated. Of the people I spoke with later, none could recall being read their rights or being offered an opportunity for counsel or to call family. As for calling family, the sheriff's officers would be making those calls themselves. Each person was ordered to provide not only their identification but the names and phone numbers of their parents, their schools, and their employers.

One of the people being interrogated was a young attorney. Once he realized the scope of what was being asked, he turned around and told the group that they only had to provide their ID and could refuse any additional questions if they wished. The sheriff's officers threatened to arrest him, but he stood his ground and they let him go. One by one, all of our members were released as the sun rose over Broward County.

In the days that followed, the problems for our members only intensified. Most of our members had their parents called, many of them outed to family members who were not ready to accept their gay children, and especially angry over the way they found out. The Broward Sheriff's Office justified its actions by claiming that there was widespread drug use occurring at the club. This stood in contradiction to the fact that out of the hundreds arrested that night, only six were charged with a crime, and none of those charges led to convictions. As for the members of the youth group, none were found drinking or with drugs. Neither I nor any of the other youth group leaders saw any such activity, and we would have intervened immediately if we had.

In the weeks that followed, we heard from many young people who were being harassed by family and school members over what happened. Several members needed more than the peer counseling we offered, and those members were referred to the network of counselors, led by Marilyn Volker, who were incredibly helpful with our members.

While it is difficult to track the full aftermath, I know firsthand of one member whose family situation became much worse, and he took his life as a result. While suicide is rarely the direct result of one event, the actions of the Broward Sheriff's Office caused suffering to hundreds, and I believe it was an important factor in this young man's death.

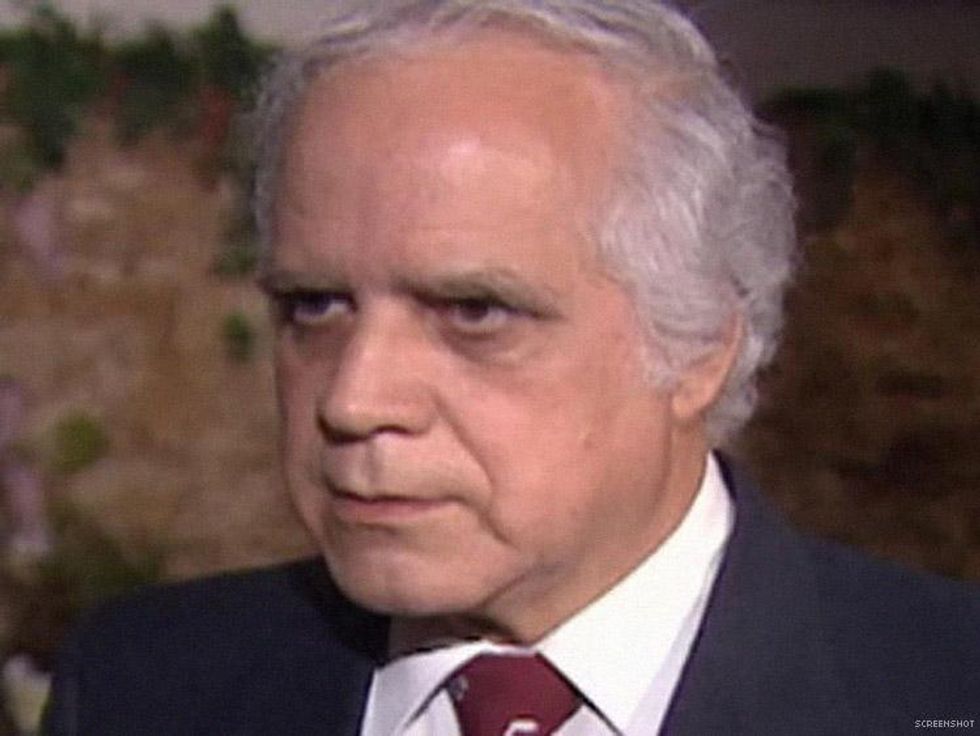

While I was not present at the Copa nightclub raid that occurred the same night, my understanding is that the same sequence of events occurred there. Importantly for the gay community and for the youth group, the owners of the Copa, located in Fort Lauderdale, decided to fight back. Their attorney, Norm Kent, began a lawsuit against the Broward Sheriff's Office, fighting against the officers' abuse. Sheriff Nick Navarro (pictured above), who had staged the entire event for the press and visiting dignitaries, found himself facing a backlash that previous raids of this nature had not experienced. In the months that followed, the various scandals of the Navarro administration finally caught up with him, and he lost his reelection bid.

The new sheriff was a much more understanding ally of the gay community and quickly settled the lawsuit and worked with gay activists to create an LGBT liaison.

While the events of that night caused harm to many, that night brought many of us to action. In the years that followed, the human rights ordinances of Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties were passed, with the hard work of many LGBT residents galvanized to bring an end to the discrimination that had plagued our community. The Broward Sheriff's Office now recruits LGBT people instead of arresting them en masse.

The LGBT community can trace many of its turning points to gay nightclubs. From the forming of the Mattachine Society to Stonewall to the massacre at New Orleans's Upstairs Lounge and to the countless other bar raids like these in Florida, much of the positive change our community has created can be traced back to these pivotal events that occurred at gay nightclubs.

While they often go underappreciated, the gay community owes a debt of gratitude to the courageous gay bar owners who stood up against societal challenges to make a place for us as well as the many attorneys working both for gay businesses and pro bono to help expand the legal foundation for gay rights.

BYRON JONES is a computer systems engineer and LGBT activist who lives in Orlando and works for a mouse. He met his husband, Brian Singleton, 26 years ago at the youth group now known as Pridelines: https://www.pridelines.org

BYRON JONES is a computer systems engineer and LGBT activist who lives in Orlando and works for a mouse. He met his husband, Brian Singleton, 26 years ago at the youth group now known as Pridelines: https://www.pridelines.org

BYRON JONES is a computer systems engineer and LGBT activist who lives in Orlando and works for a mouse. He met his husband, Brian Singleton, 26 years ago at the youth group now known as Pridelines:

BYRON JONES is a computer systems engineer and LGBT activist who lives in Orlando and works for a mouse. He met his husband, Brian Singleton, 26 years ago at the youth group now known as Pridelines:

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes