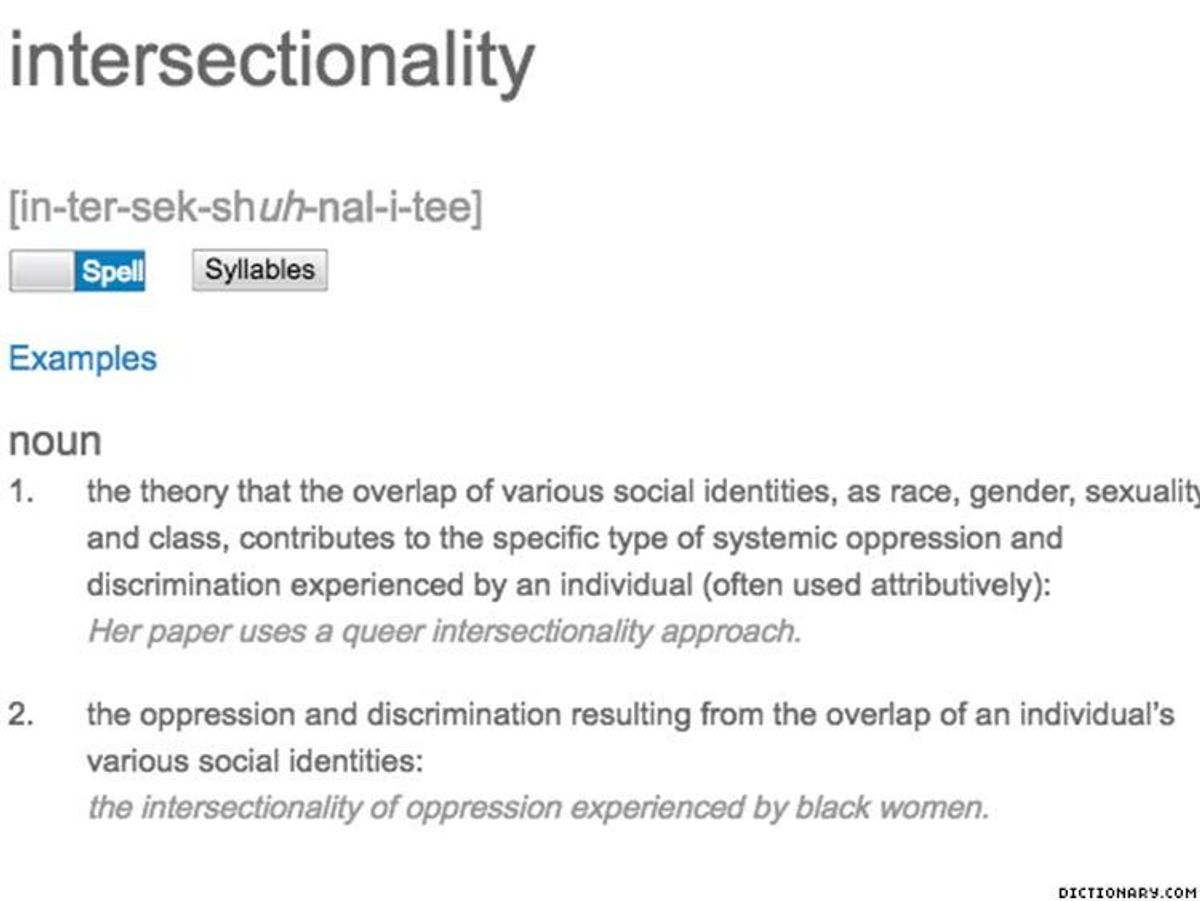

Some terms added to Dictionary.com this month relate to LGBT people. One word points to a concept many are still trying to understand: intersectionality. It's worth looking up. In fact, it is one reason this reporter has a job covering how race and ethnicity intersect with the LGBT experience, and how the systemic oppression faced by people of color is linked to that of LGBT people. Neither of these experiences or communities are mutually exclusive.

The term isn't new, nor is it the first time it has been included in a dictionary. But the word, first created by legal scholar and professor Kimberle Crenshaw to explain the layers of oppression faced by black women in a legal context, has gained momentum in popular culture. Why? Because so much of what LGBT people experience is intersectional. Just take a look at recent events to see how intersectionality plays a role.

In other words, because of identities tied to race, ethnicity, class, religion, gender identity, disability status, sexual orientation, and other markers, people experience prejudice and oppression differently and to varying degrees. And women, especially black queer/trans women, endure the harshest of both violence and invisibility.

Regular readers of The Advocate may have noticed an increase of coverage of stories centering perspectives of nonwhite LGBT people. Stories like the lynching conviction of Jasmine Richards, a leader of the Black Lives Matter movement who is also a lesbian, caused controversy in the comments sections. Some LGBT readers saw the news as a distraction from coverage of the LGBT community.

But to think covering members of Black Lives Matter is a distraction or to negate its value as LGBT news erases the fact that for many, like this reporter, the black and LGBT experiences intersect. This view also negates the queer feminist origins of the Black Lives Matter movement simply because "black" is in the name.

It's newsworthy that Richards, a black lesbian, was convicted of a charge that was formerly referred to as lynching, especially given her visibility as an activist. And considering the history of lynching -- counts by the Equal Justice Initiative document nearly 4,000 black people killed by white mobs across the country after slavery ended -- race in this case represents a key piece of information with which to understand the controversy.

As fellow Black Lives Matter leader and professor Melina Abdullah explained last month to The Advocate, it was the intersection of her identities that led to her act being charged as "felony lynching" instead of a lesser charge.

"There are vastly different experiences based on race and based on class ...for most poor black people we know there is no such thing as 'Officer Friendly,'" Abdullah said after Richards was convicted.

The Pulse shooting also gave insight into intersectionality, as it demonstrated how different groups of people were treated in its aftermath. LGBT people faced a direct attack on their identity, feeling that they could have been one of those 49 people who lost their lives. Since many of the victims were also Latino, these feelings were even more complicated for LGBT people of color.

Jose Roldan Jr., a New York-based playwright and actor, said that when he heard the news, he "froze" in fear, and then that fear turned to anger.

"A number of communities that I belong to were affected," Roldan told The Advocate. "The Latinx community as a whole, more specifically the Afro-Latinx community, the Puerto Rican community, the LGBT community, and the Latinx LGBT community. I belong to every single one of those communities."

Roldan felt the tragedy was being generalized to the LGBT community, and that "for this to happen on a Latinx night in a predominantly Latinx community is upsetting."

For Elizabeth Rivera, an activist and member of New York's famed ballroom family House of Ninja, it hit close to home too.

"I just broke down, I broke down crying," Rivera said. Until recently, she lived in Tampa, an hour away from Orlando, but she had never visited Pulse. "I thought about all the different venues I've accessed as a transgender woman. It made me start reflecting on how vulnerable I felt in that moment."

Vigils around the world expressed the resilience and strength of LGBT people. But some felt that the experience at the vigils painted a picture that erased their identity or made them feel like outsiders.

For example, Mirna Haidar, a queer Muslim New York-based activist was heckled by LGBT people while speaking at Stonewall about the Islamophobia members of her faith faced since Pulse.

And Tiffany Melecio, a University of Missouri journalism student, was shouted at by a gay male couple who felt her question about why the mourners at the university's vigil didn't show up to other demonstrations about race and social justice was inappropriate.

New Yorker Gia Love was so frustrated at the Stonewall vigil that she left and recorded a Facebook live video about her experience.

"They were telling us to leave when we were speaking the truth," Love told The Advocate. "That's very common, and it has historical implications around white men telling black people or people of color we don't belong when we should have been at the forefront of that vigil, and our voices should be heard."

People fighting the oppression exacerbated by intersectional identities may experience oppression differently than those with fewer intersections, but their experience also catalyzes change in rapid and creative ways.

"Our perspective is a genius perspective and we can take it to the next plane," hip-hop artist Mister Wallace told The Advocate. Wallace's latest EP release, f****t, by FutureHood -- a label focused on queer and trans people of color that he created with his music partner Anthony Pabey (AceboombaP) -- challenges the status quo with in-your-face reality. "Right now everything kind of exists in that plane of normativity, heteronormativity, mediocrity," Wallace said.

Wallace, who said he lost his job in corporate America because his blackness and queerness became a liability, used the opportunity to start production of his label to help others find themselves in a supportive space in the music industry.

"These queer people and these trans people of color are so visionary because they have so much perspective because their intersection allows them to see much deeper," said Wallace.

The key theme from all of these people is that listening will help LGBT people and people of color understand the complexities of their experience. Jennicet Gutierrez, for instance, said she grew in her activism because of exploring the different experiences she encountered. For her and others, it especially meant listening to those who are most vulnerable and advocating in spaces where others cannot.

"I tell a lot of my white friends all the time, it's fine we're hanging out now, you're feeling this way now," Pabey, who is Puerto Rican, told The Advocate. "But when you're sitting at Thanksgiving table and [a family member makes] that comment ... that's the moment, that's the fight, that's the revolution right there. Are you going to hold your tongue, or are you going to speak?"

Solidarity with all LGBT people is how we can work to break down the systems of oppression that affects every vulnerable group. Racism, Islamophobia, ableism, misogyny, and transphobia shouldn't exist within LGBT communities, but they do, just as they do everywhere. LGBT people should know better, and they can do better. The first step is easy -- just look up a word in the dictionary.