When was the last time you remember hearing about domestic violence among LGBT people? I am willing to bet you'll struggle to remember.

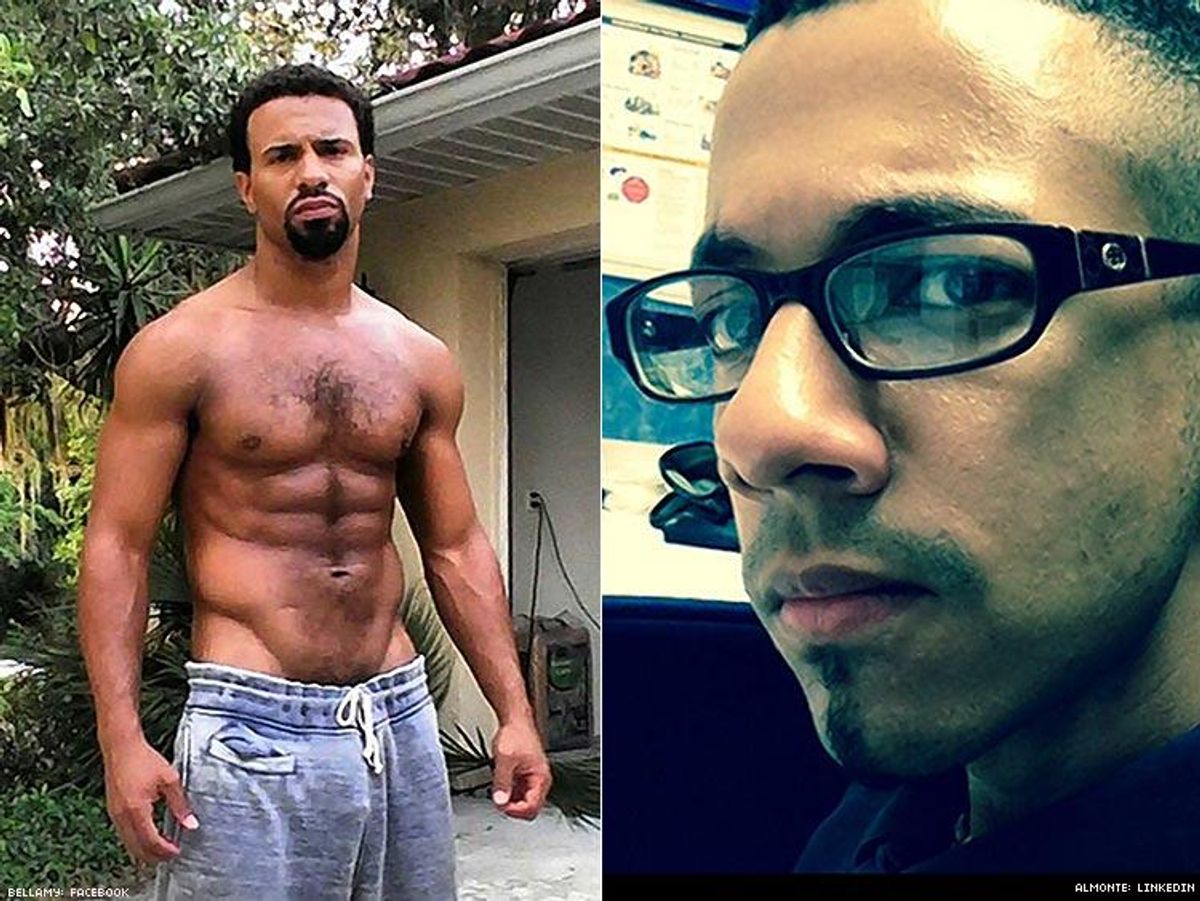

As a gay man, I often feel that the only time we ever talk about domestic violence as a community is when there is a murder in the news. Just this weekend, Broadway dancer Marcus Bellamy was arrested on charges that he strangled his boyfriend Bernardo Almonte to death.

Otherwise, we are radio silent on the issue because so many of us think it's "a straight issue." And for so many years we fought for equality and rights, and specifically for the right to marry. The perception is that if we talk about domestic violence it somehow delegitimizes that battle.

Furthermore, as a society there is this misconception that abuse in a same-sex relationship is just a fight. How many times have you heard, "Yeah, they are dating, but they're gay. It's just two guys fighting. Let them fight it out." But abuse is different than a fight. Domestic violence is one person trying to exert power and control over another. It's dangerous, and it often escalates over time.

Domestic violence in the LGBT community exists at high rates and deserves our attention.

So often, loved ones of a domestic violence victim say things like "I had no clue this was happening. I wish I had known so I could have helped. I wish I had paid closer attention." I imagine this may have been true for the friends and family of Marcus Bellamy and Bernardo Almonte. The truth is that domestic violence thrives in silence. While 60 percent of Americans say they know a victim of domestic violence, two out of three Americans have never talked about the issue with their friends. But the statistics are loud and clear: One in four women and one in seven men will experience domestic violence during their lifetime. And two in five lesbians and one in four gay men will be a victim in their lifetime.

What perhaps is even more tragic than the silence and stigma that surrounds domestic violence in the LGBT community is the severe lack of supports for those courageous enough to seek help. The current service models simply do not address the unique needs of LGBT people adequately. Although federal law now requires shelter providers to accommodate LGBT survivors, access remains limited for many reasons.

One of those reasons, as Liz Roberts, deputy CEO of Safe Horizon, writes, is that "much of the government funding to address domestic violence is geared toward families. That means we have fewer resources for childless survivors. About 40 percent of victims who call New York City's 24-hour domestic violence hotline seeking shelter are singles -- but they're the most difficult to place, because most of the beds go to survivors with children." But many LGBT folks don't have children.

So what happens?

LGBT folks who need immediate shelter may first try and stay with friends. The issue here is that the LGBT population is small and our circles tend to be interconnected. And in abusive relationships, abusers will often isolate victims from friends and family. This was true for Terrance* (name changed for anonymity), a gay Safe Horizon client, who sought refuge with mutual friends. Although they wanted to help, eventually they asked Terrance to leave because they were also friends with Terrance's ex and didn't want to pick sides.

Terrance found himself with no choice but to enter a homeless shelter where he witnessed violence and, as a result, felt unsafe and very depressed. "I was seeking out someone to talk to," he said. "I needed counseling. I was trying to inform [the shelter], 'Look, here's my order of protection. I'm a domestic violence victim. I need something a little more where I can be alone.' It's bigger than just me being homeless. I need someone to talk to. I was crying inside ... in a really rocky space financially, no money, no friends, no one to talk to, and afraid. I didn't know where this guy is going to find me. I don't wish it upon anyone."

Terrance was eventually placed in a domestic violence shelter at Safe Horizon, where, he says, he got his confidence back and was able to access the supportive services he needed. At Safe Horizon, we partner with the New York City Anti-Violence Project to make our shelters accessible to LGBT survivors.

But not everyone is able to come out of an abusive relationship as a survivor.

If there is one silver lining to the death of Bernardo Almonte, let it serve as a cautionary tale. Domestic violence is real, and it is most certainly an urgent LGBT issue.

You may be asking, What can I do if I find out a friend is an abusive relationship? First off, believe them. Don't minimize their claims. Take what they are saying seriously. Most important, understand that domestic violence is complicated. Don't force them to call the police or put pressure on them to leave the relationship. That may not be the choice they want or are ready to make. Instead, let them know they have your support and recommend they speak to an expert who can help them better understand the options available to them.

Also, donate to organizations like Safe Horizon that are on the ground supporting victims of domestic violence. One simple thing I do: I paint my left ring fingernail purple to signify my vow against domestic violence as part of Safe Horizon's #PutTheNailinIt campaign. I actually had a friend once ask me why my nail was purple, and when I told him what it meant, he told me, "I was in a relationship like that." I was the first person he ever told who believed him.

Paint your nail, donate, or be a supportive friend. No matter what you choose to do, do something. As people who identify as LGBT, we know how debilitating living in silence can be. No one should have to suffer in silence because of abuse.

Rest in power, Bernardo.

Here's our dream all-queer cast for 'The White Lotus' season 4