Tuesday's Supreme Court oral argument in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission took the case in a direction neither side may have expected. The facts are well known: Jack Phillips, the owner of Colorado's Masterpiece Cakeshop, refused to bake a wedding cake for same-sex couple Charlie Craig and David Mullins, based on his religious belief that marriage should be reserved for a man and a woman. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission ruled that Phillips's action violated a Colorado law prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Phillips was clear that his faith motivated his decision, but his lawyers framed the case around freedom of speech, not freedom of religion. The strategy behind that choice was clear. The Supreme Court long ago decided that when a law applies to everyone and was not enacted in order to suppress a particular religious belief, it does not violate religious freedom just because some people may feel compelled to violate it for religious reasons. And surely there is no better example of such a law than one banning discrimination in employment, housing, or public accommodations.

Because of this well-established precedent, Masterpiece Cakeshop's lawyers made the strategic decision to try to shoehorn their case into a line of Supreme Court decisions striking down, on free speech grounds, laws that forced individuals to communicate a government-approved message. Their briefs described Phillips as a "cake artist" and waxed poetic about the creative energy on display in his creations. They argued that making a wedding cake implicates the baker in celebrating the couple's marriage; thus, forcing Phillips to sell a wedding cake to Craig and Mullins would force him to use his artistry to send a message -- approving a same-sex marriage -- he didn't want to send.

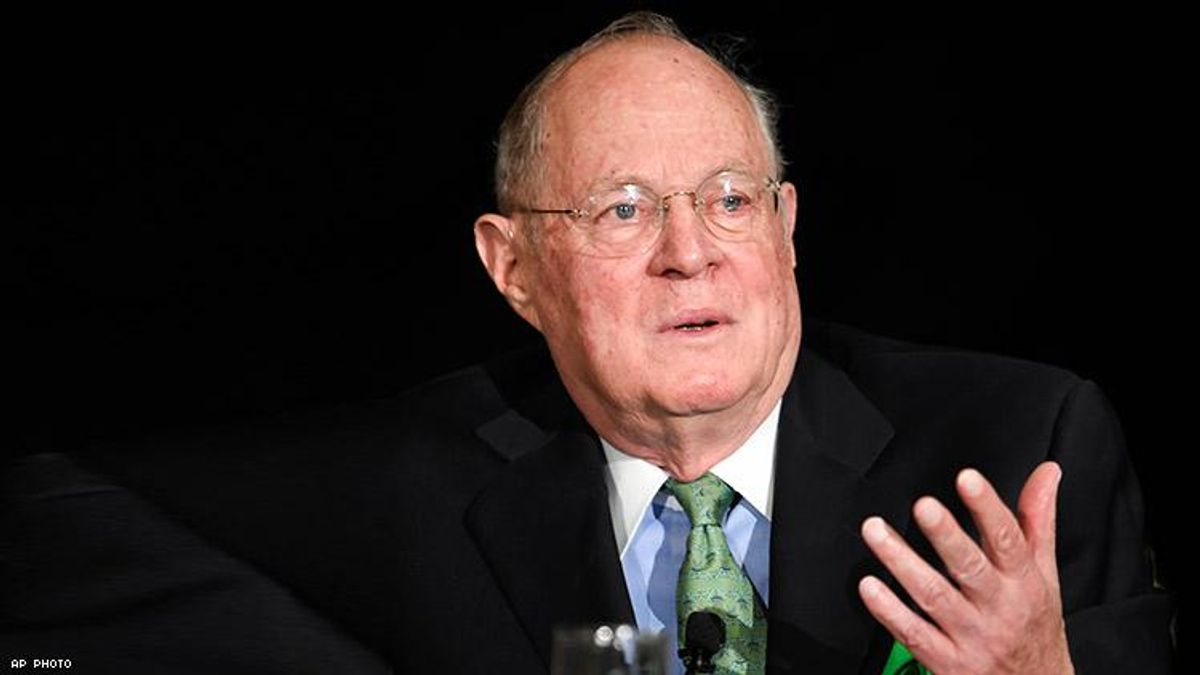

The compelled speech argument fit awkwardly with Phillips's own faith-centered account of why he turned Craig and Mullins away, and Tuesday's argument revealed that at least five justices appear skeptical of the speech argument. Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan peppered the lawyer for Masterpiece Cakeshop with questions that highlighted the difficulty -- if not impossibility -- of determining when a business is being compelled to speak when its goods or services are used at a wedding. If the baker is "speaking" at the wedding, why isn't the florist, hair stylist, or makeup artist? If a wedding cake is protected speech, why should it matter whether the business is creating a custom-made product or selling a previously made product off the shelf? Justice Anthony Kennedy also seemed uncertain about how the court could draw such lines.

The same justices expressed concern about Masterpiece Cakeshop's compelled speech theory for an additional reason. The rule sought by Masterpiece would open the door to an almost limitless variety of claims for exemptions from antidiscrimination laws of all kinds. Nothing about the compelled-speech argument is limited to antigay discrimination or to weddings, and almost any business could argue that its products and services are artistic or creative. As Justice Breyer observed, the compelled speech argument would "undermine every civil rights law," including those prohibiting discrimination based on race, sex, national origin, and religion.

Justice Kennedy also worried that a ruling for Masterpiece Cakeshop on the free speech claim would promote widespread discrimination against gay people. Because there are "so many examples" of businesses that could claim their goods and services involve speech, he noted, such a ruling would mean "that there's basically an ability to boycott gay marriages." What if Masterpiece Cakeshop won, and then "bakers all over the country received urgent requests: Please do not bake cakes for gay weddings. And more and more bakers began to comply"? Under Justice Kennedy's questioning, United States Solicitor General Noel Francisco made a stark and startling admission: A victory for Masterpiece on the free speech claim would mean that a baker could hang up a sign saying that "he does not make custom-made wedding cakes for gay weddings." Justice Kennedy described that prospect as "an affront to the gay community."

Based on these exchanges, it appears that a majority of the court is unlikely to endorse a new constitutional exception to antidiscrimination laws based on the notion that bakers are "cake artists" or are being compelled to send messages with which they disagree. But at the same time he expressed doubts about the speech argument, Justice Kennedy had harsh words about the Colorado Civil Rights Commission's treatment of Phillips's religious beliefs.

Questioning the attorney for the state of Colorado, Justice Kennedy pointed to a statement by a member of the commission who referred to the Phillips's use of religion to justify discrimination as a "despicable piece of rhetoric," similar to that used in the past to defend slavery and the Holocaust. Clearly troubled by the commissioner's harsh language, Justice Kennedy asked whether the Supreme Court could uphold the lower courts' decision in favor of Craig and Mullins if the court was persuaded that "at least one member of the commission based the commissioner's decision on ... hostility to religion."

Justice Kennedy's discussion of anti-religious bias points the way to possible resolutions of the case that were not anticipated by either side. In particular, Justice Kennedy might join with Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan in rejecting the compelled speech claim, but write a separate opinion voicing his concerns about possible anti-religious bias in Colorado's treatment of Masterpiece Cakeshop. Such an opinion would express concern about the commissioner's statements but stop short of concluding that the Commission's decision infringed Phillips's religious freedom. Or, if a majority of the justices believe that the commission's decision may have been tainted by anti-religious bias, the Court could send the case back to the Colorado courts for reconsideration.

Either way, Justice Kennedy's desire for a resolution that both protects gay people from discrimination and respects sincere religious beliefs offers important lessons that transcend the immediate legal issues in this case. If there is a big-picture takeaway from Justice Kennedy's remarks, it is the importance of reaching across cultural divides to build more mutual understanding and support. This case gives those on both sides of these issues opportunities for dialogues that we might not otherwise have. We should approach those opportunities with a keen sense of our mutual interdependence and the need for mutual respect.

SHANNON MINTER is the legal director for the National Center for Lesbian Rights. CHRISTOPHER F. STOLL is a senior staff attorney at NCLR.

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella