In the cacophony of executive orders, Twitter wars, and cringe-worthy moments watching White House adviser Kellyanne Conway spin her "alternative facts," we can easily rush to hate. It's infuriating, but it all feels startlingly familiar to me. In 2007, I campaigned with a Parliament candidate in Kenya named Emmanuel Leina. Emmanuel is Maasai, but converted to Christianity. While campaigning, it didn't matter that I was gay. What mattered was that we both shared his vision of a nation founded on principles of peace and equality.

But a presidential election was also going on. The incumbent president, Mwai Kibaki, was accused of stealing the election, resulting in post-election violence that displaced 600,000 people, killing about 2,000. Both Kibaki and his rival, Raila Odinga, urged their supporters to give in to passions for discrimination to better serve their rise to power.

Thus was born my documentary film A Chance for Peace. It's been a nine-year saga that has included immersive peace research in Thailand, India, Germany, Turkey, Egypt, Mexico, and Kenya. Now, as I experience firsthand the mirroring of the corruption and divisiveness I was only a witness to in Kenya, I'm ready to share some lessons learned from almost a decade of researching the role of peace in politics.

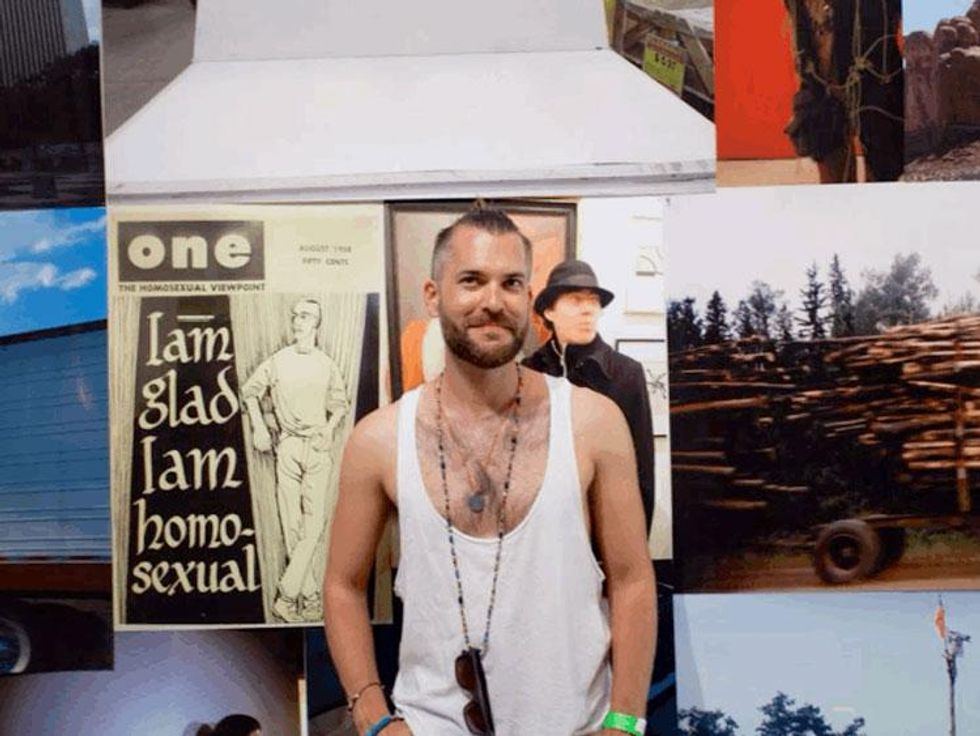

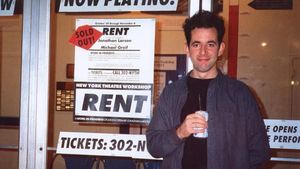

Above: Writer-director Tyler Batson at an anti-Trump rally in downtown Los Angeles.

1. We cannot know a thing without first knowing its opposite.

We cannot have a resistance without resilience -- and who knows resilience better than the LGBTQ community? At this point in our movement's history, we have fought systems of oppression and have shown that we are no longer victims, but leaders. But we mustn't forget that our true enemy is not Donald Trump, but hate itself. It is only then that we can focus on our real weapon in this war: love.

After all the strides we've made, we must maintain the steadfast conviction that love can win. The path ahead is therefore two-pronged: We must be the voice of discontent and accountability, while concurrently cultivating a more just and inclusive environment. Simply put, two opposing forces go to war; two complementary forces find peace.

2. In pain, I see a chance.

In The Book of Joy, the Dalai Lama says the antidote to bitterness is finding purpose in suffering. So in this maelstrom of political mayhem, what is our purpose? LGBTQ people have overcome the pain inflicted on us by an unwelcoming society, and from that pain we've found pride in our identities. We've faced off with ignorance and found freedom, and after nine years of researching, practicing, and bearing witness to peace all over the world, I can tell you that the LGBTQ community stands tall among the giants of peace-building. That didn't start because we were oppressed; it started because we exist. Now, once again, we get to show the world what our existence stands for. Is it the pain of the past or the peace of the future?

Above: Tyler Batson posing with the Mattachine Society's One magazine at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

3. This is all part of an evolutionary process.

In November 1950, the Mattachine Society -- American's longest-running LGBTQ organization -- was formed. One month later, Congress deemed homosexuality a "mental illness." Two years later, the American Psychiatric Association asserted that homosexuality was a "sociopathic personality disturbance."

So what did we sociopathic, mentally disturbed homos do? We organized. Today, the gay agenda stands firmly on a message of love and tolerance. As we look around at our chosen families it's time to not just demand a seat at the table, but to make room for others. We are L's and B's and T's and Q's and I's, but we are also black and Latino and immigrants and Dreamers and environmentalists and citizens of a truly global movement. We and those who came before us have set us up to lead. How society evolves depends on us.

Above: Still from A Chance for Peace: artist turned "messenger of peace" Solo 7 engaging youth in a conversation on peace.

4. Peace is not something you think or something you feel; it's something you do.

Our understanding of peace is as deep as our practice of peace. The people I met in Kenya started youth groups, raised tens of thousands of dollars, built schools, created art for peace, and even healed the seriously ill. When I asked them how they managed to do it, all of them said the same thing: "We are just doing the best we can with what we have." If we want things to change, we have to show up with the skills and resources already at our disposal and do things differently. It's only then that we'll learn just what we're capable of.

5. We are one human family.

We members of the LGBTQI community know what it's like to begin again, and we know that love wins. But make no mistake, love is work! We walk out of the house every day aware of the challenges we face. But we roll deep! We are supported by a long history of LGBTQ leaders who have done the work of peace-building. By virtue of our existence, we are party to a movement that's transformed fear and hate to acceptance and love.

Now is the time to get out there and take that narrative ol' pie-in-the-face Anita Bryant gave us of "the gay agenda" and do what we're really here to do: show people how to love more and hate less.

TYLER BATSON is the filmmaker of A Chance for Peace, a nine-year journey of exploring peace movements across the globe.