Voices

We’re Here. We’re Queer. We’re Invisible

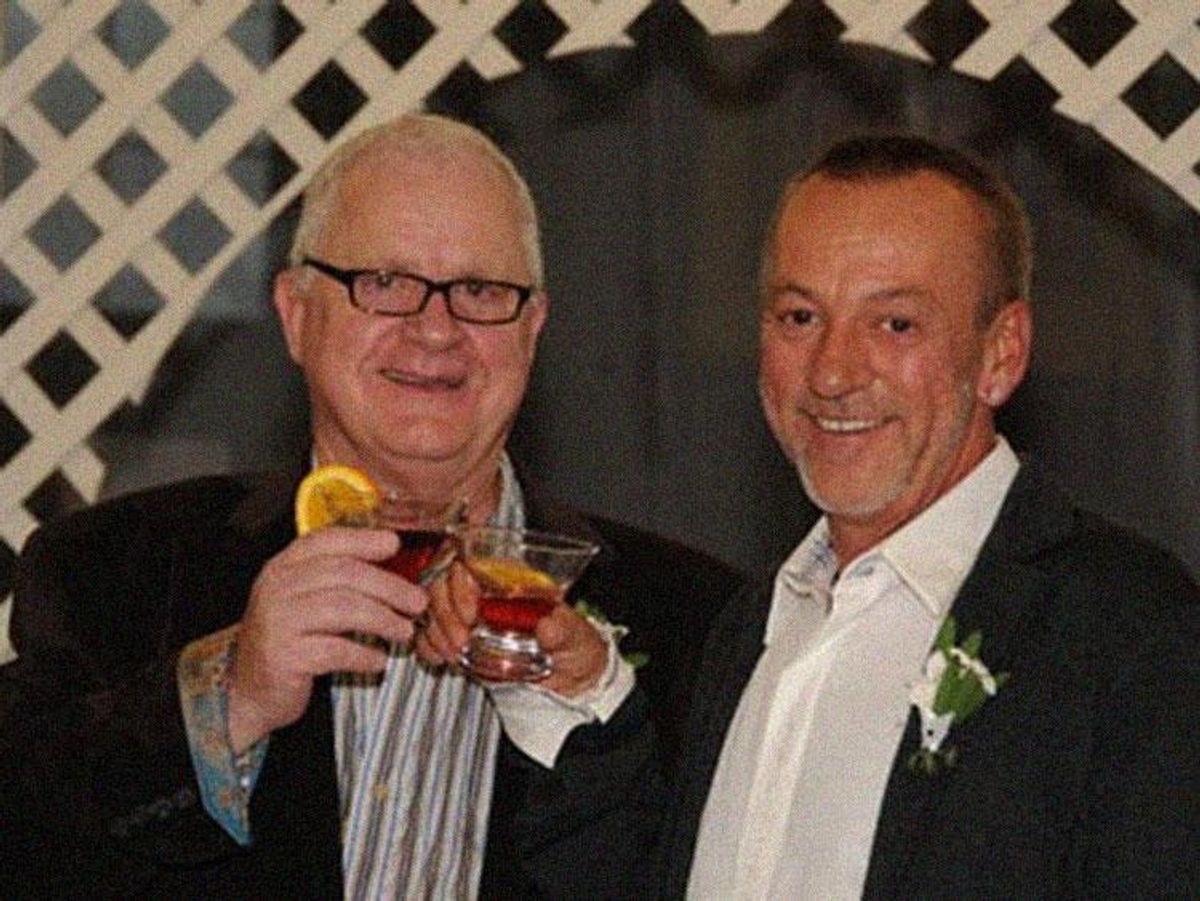

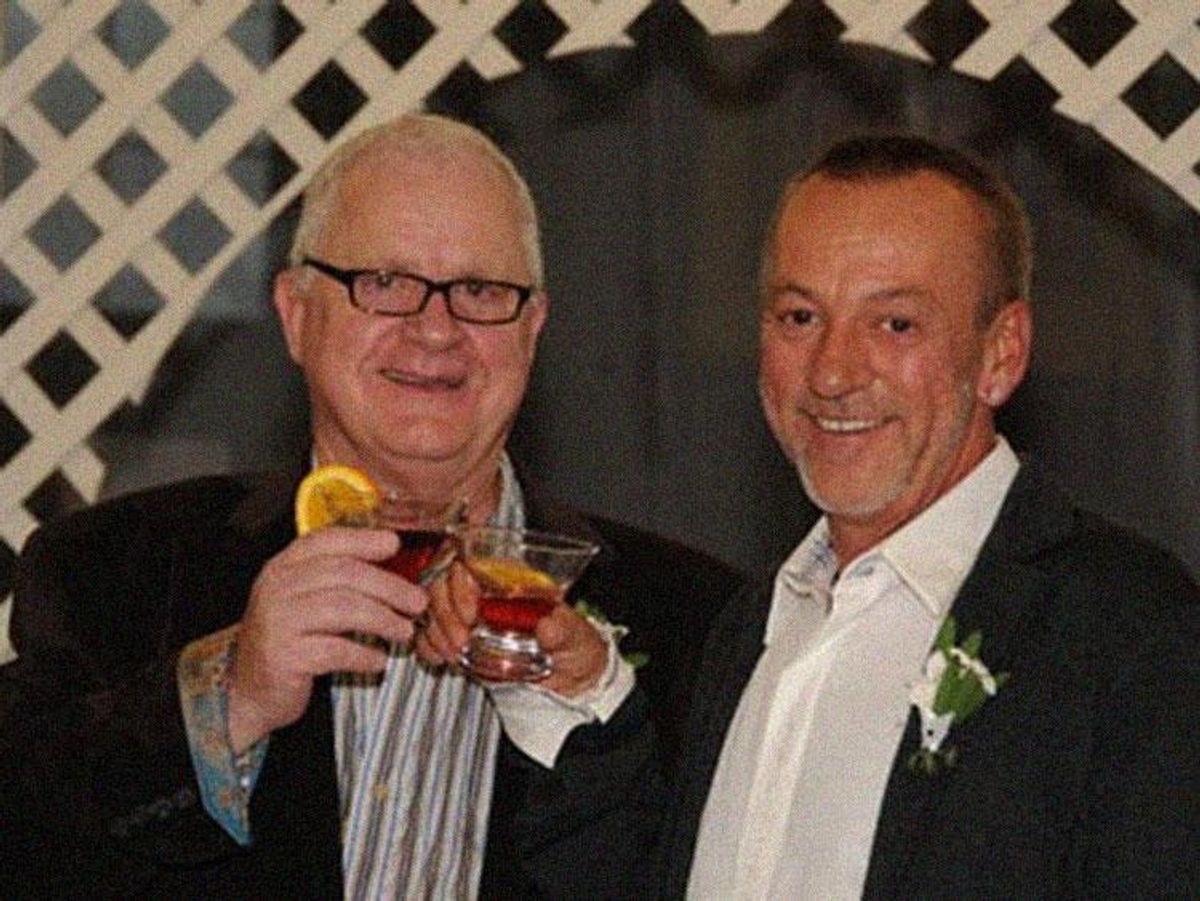

Loren Olson (left) moved from the big city to start a farm in Iowa with his husband. Gay life is where you find it, he writes.

April 20 2017 1:47 AM EST

April 20 2017 3:46 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Loren Olson (left) moved from the big city to start a farm in Iowa with his husband. Gay life is where you find it, he writes.

When Iowa enacted marriage equality, the fourth state to do so, I heard from a lot of friends, "Iowa? Of all places!" It seemed like being queer and living in a rural state like Iowa was incompatible, as if those of us who live in rural areas are considered by the LGBTQ community as not authentically gay.

And yet according to the 2010 U.S. Census, over 900,000 same-sex couples live outside of urban areas, a number that has increased by half since the 2000 census. Of those couples, 12 percent live in rural areas and 7 percent live just outside of suburban areas.

When Doug and I bought our farm in 1995 and moved just outside of a town of 450 people, a lot of our neighbors quietly shook their heads with a bit of a smile on their faces. You could almost hear them thinking, These two sissy boys from the city think they can become farmers. No one ever said anything about our being gay other than "Oh, you must know Tom and Dan," another gay couple in the area that after 20 years we still haven't met. Although I had secretly expected to see "f****t" painted in big white letters across our red barn, nothing like that ever happened.

But we took our farming seriously, just not in the agribusiness way most farmers in Iowa do. We developed a business plan for raising grass-fed beef and lamb in an area where farmers overproduce corn and soybeans and plow every inch of available soil to do so. Not only were we gay, but producing grass-fed beef made us heretics as well. Neighbors thought our Belted Galloway cattle belonged in a zoo.

Our credibility with our them changed when they saw us selling small breeding herds of our cattle at premium prices from California to Washington to Texas to North Carolina. Perhaps our previous urban life gave us an awareness of the growing market for grass-fed meat, and our lack of ties to traditional farming allowed us to innovate in ways that those with deep roots in Iowa soil didn't have.

Farming is a high-risk business adventure. My stepfather, a retired cattle farmer, said, "I think you have the secret to successful farming: Have a medical practice on the side." To be sure, many farmers, especially small farmers, depend upon an off-the-farm source of income. But even with a psychiatrist's income, with 200 head of cattle and 400 acres, we couldn't have sustained a huge loss.

I wrote in Finally Out: Letting Go of Living Straight that as we become older we can deconstruct our old value system and reconstruct a new one better suited to the life we choose to live. I had to do that when I came out at 40. But reconstructing a new one doesn't mean we must throw out all of our values and replace them with new ones, and living a country life was one of those values I wanted to protect.

Of course, we wished to live in a bucolic area, but that alone doesn't sustain you when you must get up at 3 a.m. to assist a ewe that is having difficulty giving birth to her lamb. Both Doug and I enjoyed a sense of community with others who farmed, and we loved the idea we could walk away from our house without locking the door every time we left. We shared a concern about environmental devastation and planted over 7,000 trees and restored a few acres of prairie for the monarch butterflies and ring-necked pheasants.

We loved seeing earthworms return to the soil that had been depleted with chemicals. At night, we can hear the frogs calling for their future mates and the coyote pups calling out for their mothers, and sometimes it's difficult to tell the lightning bugs from the stars.

We are not alone in this. One of the most surprising things in the 2010 census was how far from the traditional gay enclaves couples have dispersed. San Francisco fell from number 3 to number 28, while gains were made in New England, east Texas, North Carolina, Alabama, and Kentucky. As we grow older, drinking and dancing the night away have lost their luster. Couples (and probably singles, although not collected in the census data) have chosen to move to areas that are gay-friendly but not gay-exclusive. Identity politics are a low priority in rural America. Saying "queer" in rural Iowa results in the same reaction one might get when using the n word.

Those of us who are queer here in rural America are largely invisible, as if we live in a brown paper bag. Small towns have always had a couple of men or women who were roommates and lived quietly among the community. Those men were often referred to as "confirmed bachelors" and the women as "old maids," but they were largely accepted without questioning the nature of their relationships.

Early research on the LGBTQ community was primarily done on young, self-identified gay men. Urban queerness cast a large shadow over rural queerness. So, what happens to advocacy for men and women who don't fit the urban mold? Are we less worthy members of the gay community? As I was planning my book tour for Finally Out, scheduling a signing in a large city, the community resource person suggested that they get a local LGBTQ leader involved, as if to say, "What could someone from Iowa know about gay life?"

For us, eating out might be picking up a pizza at the local convenience store. Cultural events are attending the county and state fairs. Sometimes we long for closer associations with a community of gay friends. But we do understand gay life, albeit from a different perspective.

Chances are good that the number of LGBTQ people in rural America will increase, but we won't know that. There will not be a question about LGBTQ identity in the 2020 Census, as some of us had hoped.

In the past, gay people escaped the countryside to find a new life in the city. Now it appears that many are escaping the city to return to the countryside.

We are here. We will remain invisible unless we raise our voices. We are an important part of our economy. We can help repopulate rural communities and bring innovation and new products. That creativity has always been a dimension that gay people have brought to our lives.

LOREN A. OLSON, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist who has been in practice for more than 40 years. A nationally recognized expert on mature gay men, he has spoken to groups across the country and appeared on Good Morning America in addition to giving numerous national, local, and regional television, radio, and print interviews. He is a regular blogger for The Huffington Post and Psychology Today. Olson lives in Iowa with his partner of 30 years, Doug, who became his husband in 2009 after the Iowa Supreme Court sanctioned same-sex marriage. He was previously married to his wife, Lynn, and is the proud father of two daughters and a grandfather of six.