In February, we first heard of the illegal detentions and torture of over 100 Chechen gay men, including three murders -- the launch of a gay pogrom. The global outcry that's followed -- marked by #FreetheChechen100 -- often carries the rejoinder "Never again!" But is that reality, or rhetoric? After all the genocidal lessons of the past, the Holocaust, Armenia, Cambodia, Rwanda, and now the Congo, will we really be able to stop the killers?

Too often, we -- the global citizenry -- have failed to halt genocide, despite our best intentions. The live burning of Yazidi women in iron cages by ISIS last June for refusing sex (read rape) tops my list of global moral failings; I wanted to vomit. Where were we -- all of us? Too quiet, too uncaring, too slow to respond. Ultimately, perhaps horrified into silence and numbed into inaction.

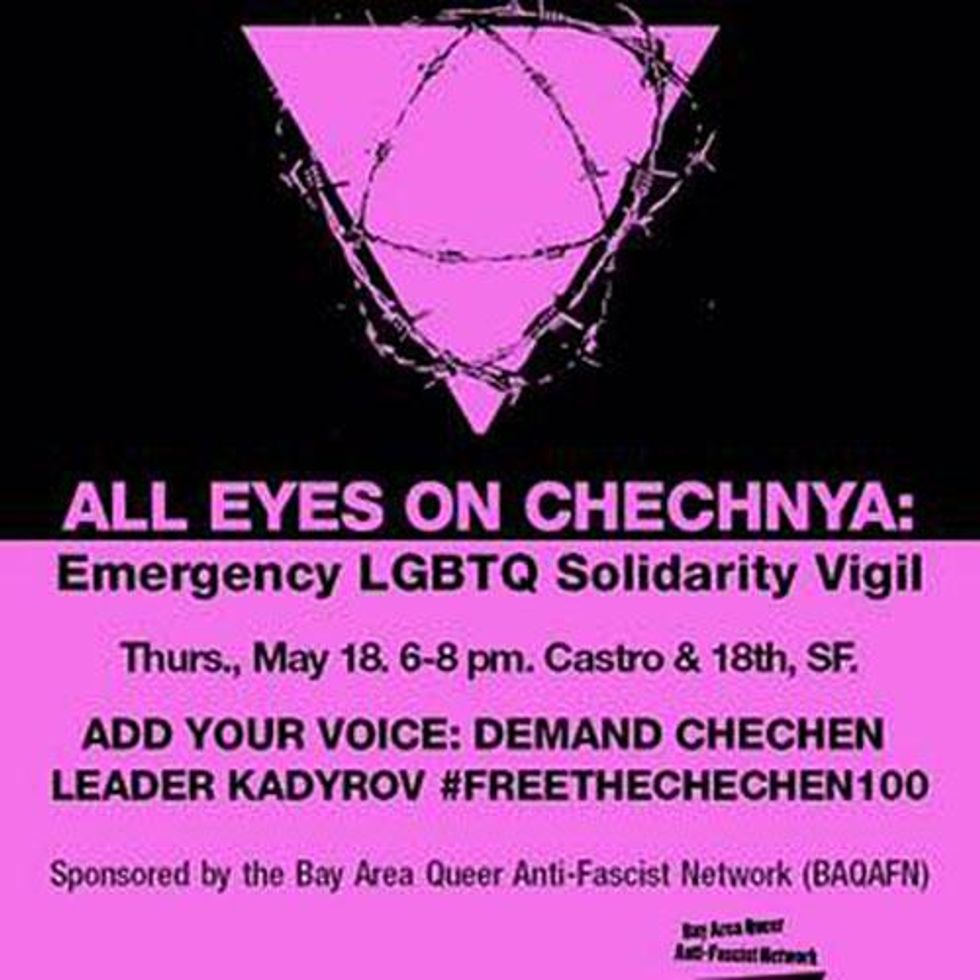

And now? What's our strategy for stopping the new brutal campaign by Chechen tyrant Ramzan Kadyrov to wipe out homosexuality? The numbers are comparatively small: 100-plus gay or bisexual men, many younger. An estimated half of them married with big families, some in arranged marriages. What's new is the unprecedented escalation of entrenched state-sanctioned homophobia, and the genocidal intent of this campaign: to eradicate gays as a group, a class of citizens.

But as Chechen advocates remind us, these tactics aren't new: kidnappings, extortion, torture, disappearance. All have been leveled for years against many sectors of Chechen society and stem in part from Russia's effort to suppress a pro-independence movement and now Islamist groups. Chechnya has been deemed a terrorist region, Chechens de facto criminalized. While our moral imperative now focuses on gay men, a large, unknown number of Chechen citizens languish in illegal detention, others disappeared. Call it #NoOneEvenKnows.

Chechen activists are demanding greater action and effective international solidarity. Already there are tangible results: The global LGBTQ movement quickly mobilized to denounce the arrests and petition Russian President Vladimir Putin for an investigation and the release of the detained. In my conversations with a dozen front-line actors -- Russian and Chechen LGBT advocates, U.S., Canadian, and European stakeholders -- there's clear consensus that the global solidarity effort is having an impact.

They cite a combination of interventions: a high-level meeting of German Chancellor Angela Merkel with Putin; a group protest letter by European foreign ministers and one by the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights; myriad backdoor entreaties by diplomats to the Russian and Chechen leadership; and most visibly, public protests at Russian embassies by LGBTQ and human rights groups.

These have struck a nerve with Putin. Russia doesn't welcome the negative attention, while Kadyrov appears confused over the gay furor. The arrests have been halted -- for now. Should the pressure wane, advocates warn, the gay pogrom could resume, and even encourage others to follow suit.

As of this writing, the Chechnya situation remains dire. An unknown number of gay men remain detained. Human Rights Watch and other monitors can't verify the disappearances nor rumored gay arrests last week, nor any recent releases. (HRW did verify some releases in April.) Inside Chechnya, no civil society group dares speak out. All Chechen gays can do is attempt, via family and private networks, to get out. And some have. The Russian LGBT network evacuated 42 individuals to relative safety outside Chechnya. Of 80 calls to its hotline recently, 56 involve gay men among the Chechen detainees.

If they get released, where can they go? Not back home. In tradition-bound Chechnya, anyone labeled gay is marked for murder, whether by the regime or relatives. Parents are implored to kill their gay children to save the family's so-called honor from the perceived stain of homosexuality. If not, other sons and daughters can no longer marry. Such honor killings are not new. But as in Rwanda's Shoah, they pit neighbor against neighbor, parent against child.

How many gay honor killings occur is a big question mark. Chechnya's population is around 1.25 million; some 5 percent to 10 percent might be LGBT. How many are among Europe's 150,000 Chechen refugees now is another question mark.

The mandate for activists now is to increase international pressure on Putin and Kadyrov, and to finance the LGBTQ grassroots groups to carry out further evacuations and resettlement activities. More money is needed for safe passage, requiring expedited visas. The main organizations deserving your donations are The Russian LGBT Network, RUSA LGBT in New York, and Rainbow Railroad in Canada. Activists also want Kadyrov's Instagram and Facebook accounts shut down. Their tweet? Stop normalizing Kadyrov; he's a vicious killer.

But there's still a serious gap: political will. That's where international solidarity hits a hard wall of prejudice and asylum fatigue directed at Muslim refugees.

So far, Canada offers the brightest beacon, as talks are under way about a plan to fast-track visas for the Chechen LGBTQ asylum-seekers. Still, no actual visas have been proffered. The U.S., enmeshed in Trump's build-the-wall policy, has provided just one. It's a shameful number that advocates vow to increase. The United Kingdom is no better; despite noise in Parliament, no visas followed -- yet. Across Europe, LGBTQ activists say that, pretty and stern words aside, their governments appear confused, the policy weak, lawmakers vulnerable to rightwing populist critics. It's also true that Chechen gays don't want to stay in Europe: Their relatives may hunt them down. Any of our governments could decide to provide the needed visas, make a hard deal with Putin. Unilaterally or as a bloc. That's a key message to bring to our leaders, one we can make June 2, a U.S. national day of action called by RUSA LGBT and Amnesty International. Commit yourselves. #FreeTheChechen100. Give them refuge. Never again!

ANNE-CHRISTINE d'ADESKY is an Oakland-based journalist and author of the forthcoming book The Pox Lover: An Activist's Decade in New York and Paris (University of Wisconsin Press, June).

Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' has MAGA hot and bothered