All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

As soon as movies started being produced at the end of the 19th century, the other two arms of what would become the film industry -- distribution and exhibition -- were created in order to make the new medium commercially viable. Studios sent the growing network of theaters not only canisters containing reels of film but also campaign books instructing exhibitors how to attract customers with eye-catching posters of all sizes, from 22-by-28-inch half sheets to billboard-size 24 sheets as well as sets of 11-by-14-inch lobby cards and 8-by-10-inch stills, not to mention window cards, programs, heralds, standees, and other lobby displays.

All this movie paper was technically on loan from the studios and like the films themselves was to be returned immediately after the film's run so it could be sent out again to other theaters. This cycle would continue until the film went out of circulation and until the movie paper fell apart from use and reuse. Add to this the World War II paper drives and that theaters often didn't bother returning the posters but just threw them out afterward, and we have a partial explanation for the rarity and high prices paid by today's collectors for original movie paper from the Golden Age of Hollywood. But think of it: It's possible to own a piece of movie history, a poster or lobby card that once hung in a theater display case. The thumbtack and staple holes, tears and crude repairs are a record of its travels, a badge of authenticity. Unlike a DVD, a studio movie poster is a first-generation souvenir of the film.

Trending stories

I've been accumulating movie paper from gay-themed films since I first ran across The Queer Movie Poster Book by Jenni Olson (2004), which compiled a history of gays in films through the posters used to promote them, much as Vito Russo's book The Celluloid Closet (1981) chronicled the portrayal of LGBT characters in the movies themselves. That pictorial history became the subject of an exhibition I recently curated called "LGBT Movie Poster History & Iconography" at the Seton Gallery on the campus of the University of New Haven, where I teach English and film. The exhibit consisted of 115 pieces culled from my collection -- everything from the original German program from Madchen in Uniform (1931) and a still of Buddy Rogers and Richard Arlen looking lovingly into each other's eyes from Wings (1927) to 27-by-4-inch one-sheets from Blue Is the Warmest Color (2014) and Der Kreis (2014) signed by the director and both stars.

LGBT films have a long, rich, and troubled history. For over a century that portrayal went from flamboyant sissies and mannish women to no representation at all, save in subtle portrayals and allusions that astute moviegoers were able to decode. Later, LGBT characters were depicted as a social problem, lonely and isolated, often dying at the end, frequently by their own hand, or else as unstable psychopaths and predators -- and of course as the butt of jokes. Some well-meaning Hollywood films sought to portray gay characters in a sympathetic light, but it wasn't really until queer filmmakers began telling their own stories in films mostly below the "gaydar" of the general public that we could hope to see movies with characters recognizable to ourselves.

A parallel history exists on paper in the photographs, artwork, and taglines of LGBT movie posters. Comparatively few gay-themed films get a theatrical release, so one must seek out those films on DVD, via internet sources, and at the plethora of LGBT film festivals held all over the world. Similarly, collecting LGBT movie art involves scouring online auctions and ads and attending the occasional movie collectors' show. Besides U.S. paper, there are foreign posters for American films, quite often with better images and artwork, or showing a key scene from a film. And of course other countries produce gay-themed films, amd in the case of these a "country of origin" poster is more desirable. Collecting this movie paper is like reconstructing and preserving the fossil record of gay lives on film.

My show was organized into categories gradually leading to the present. Walking into the gallery one was greeted by a standing closet, the door half open or closed as befits one's point of view, inside of which was displayed the one-sheet for the film documentary version of The Celluloid Closet (1995), my tribute to the late Vito Russo, to whom the show was dedicated. I also displayed a letter Vito wrote me in 1986 after he attended a talk I gave in New York City, offering to share his research with me -- that was the kind of generous person he was. "In the Closet" continued with a wall of lobby cards from movies featuring gays and lesbians from the famous to the obscure. My printed gallery guide identified each actor, including a Cary Grant lobby card from Bringing Up Baby (1938), the very scene where Grant explains why he's dressed in Katharine Hepburn's nightgown by jumping up and yelling, "I just went gay all of a sudden!" -- the first time that word was spoken on-screen in its contemporary usage.

Another category was "Exploitation & Underground." Exploitation films masqueraded as documentaries but gave their subjects tabloid treatment; these included Chained Girls, The Fourth Sex, and The Christine Jorgensen Story. So-called underground films were made on minuscule budgets with characters or actors on the fringes of society. Included were Andy Warhol's Lonesome Cowboys, Super 8 1/2 by Bruce LaBruce, and Pink Narcissus by Anonymous (actually artist James Bidgood, who constructed all the elaborately kitschy sets in his apartment), plus rare stills from Song of the Loon, based on Richard Amory's famous pulp novel in which white frontiersmen and Native Americans made love, not war.

The next film cluster, "Coded Images," refers to those subtle allusions that required reading between the lines during the era when the Production Code forbade the overt portrayal of homosexuality. Sometimes by isolating a scene from a film -- called "foregrounding" -- we finally see the significance of what was right before our eyes. I used a Spanish lobby card and an Italian "photobusta" from Lawrence of Arabia (1962) to show scenes between Peter O'Toole as Lawrence and his teenage Arab lover (Michel Ray). As far as I can tell there's no representation of their relationship in any American posters or lobby cards.

Once identifiably queer characters began to appear in movies the cumulative effect was shocking and dispiriting. "Gay Necrology" was a visual representation of the list of gay film deaths, often self-inflicted, like that compiled by Vito in the back of his book: A wall of posters and lobby cards showed the fate of gays in The Fox, The Sergeant, Ode to Billy Joe, Victim, Suddenly Last Summer, The Children's Hour, The Detective, Death in Venice, The Fan, etc. Similarly, "The Way We Weren't" was a category showing gay stereotypes at their cringiest, such as a Mexican poster with Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy (1969) beating up a pitiful, self-hating older gay man. Joe, in the course of robbing him, knocks out the man's dentures, then jams a telephone receiver into the man's mouth -- and Buck's the film's hero! Another example of foregrounding, and the film was directed by John Schlesinger, an out gay man. But he atoned with 1971's Sunday Bloody Sunday, with its well-adjusted gay and bisexual protagonists and a male-male kiss -- that poster and image also on display.

From the mid '80s onward new, queer voices were joining the chorus. The poster for the documentary Word Is Out (1977) with its tagline, "Stories of Some of Our Lives," heralded the next category, "The Way We Are." Posters and stills from the so-called New Queer Cinema included Bill Sherwood's Parting Glances; Jim Fall's Trick. showing Miss Coco Peru and her tagline, "It's Big, It's Beautiful and You're Gonna Love It"; a Polish poster for Gus van Sant's My Own Private Idaho and Maria Maggenti's hilarious The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love; plus U.K. posters for Maurice, The Crying Game, and My Beautiful Laundrette, to cite just a few. Another category, "AIDS Cinema," has in recent years been revisited by contemporary filmmakers. Included here were lobby cards from Hollywood fare such as Philadelphia but also Spanish lobby cards with key scenes from Longtime Companion, risque theater posters from Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, and the one- sheet for Gregg Araki's The Living End.

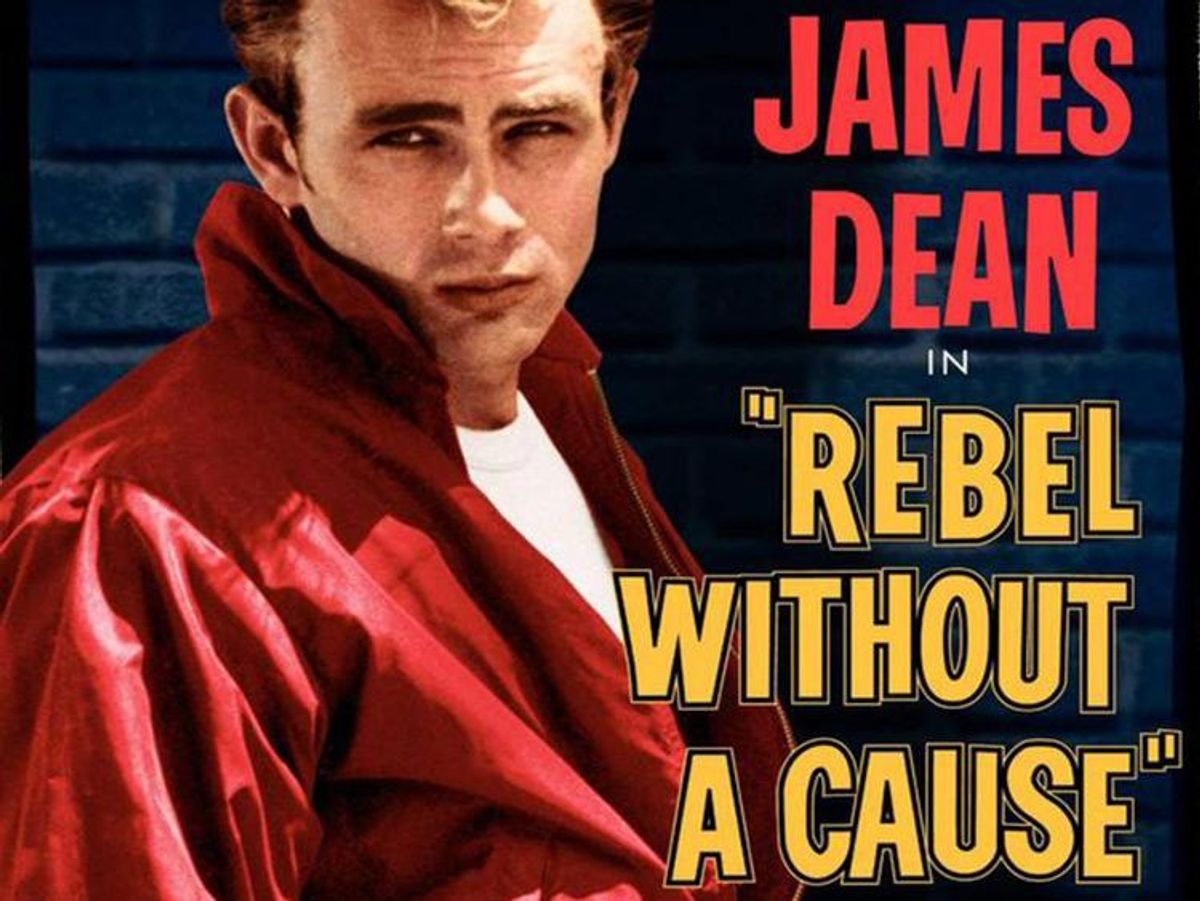

The final categories, "Coming of Age" and "New Queer Cinema," highlight the contemporary era. Stories of young gay people coming out to parents, friends, and themselves remain a staple of LGBT cinema. From Rebel Without a Cause (1955), an early example, came a British "Front of House" color still of James Dean embracing Natalie Wood while flirting with the young Sal Mineo. American posters and lobby cards omit Mineo's image, apparently because he didn't sign an exclusive studio contract. Also displayed were country of origin posters from This Special Friendship (France, 1964) and Lasse Nielsen's Danish classic You Are Not Alone (1978) as well as the lesbian romance Summertime (2015) and the erotic thriller Stranger by the Lake (2014), both from France. Included too were recent film festival posters for Kill Your Darlings and for Brazil's The Way He Looks, signed by costar Fabio Audi.

I like to quote Armistead Maupin's opening lines, spoken by Lily Tomlin, of the film version of The Celluloid Closet: "In a hundred years of movies homosexuality has only rarely been depicted on the screen, and when it did appear, it was there as something to laugh at or something to pity or even something to fear. Hollywood, that great maker of myths, taught straight people what to think of gays and gay people what to think of themselves." Homosexuality is no longer "rarely" portrayed on screen, but older gay films and the posters used to promote them provide a perspective and context for measuring progress in the present. LGBT movie paper is far less accessible than the films themselves yet arguably just as important. Each poster or lobby card is a distilled statement of that film's theme, and like a book's cover, it can be judged against the film itself.

Film is a medium that exists in time; movie posters exist in space -- as memory triggers and artifacts of our film experience. After first seeing Brokeback Mountain I felt stunned and awed by its harsh beauty and Greek-like fatalism. Of course I bought the DVD, but among my souvenirs now are the one-sheet poster, French and German lobby cards (no U.S. cards were issued), and my rarest prize --the official studio campaign book. It's almost lobby card-size, with 80 glossy color pages of photos, frame blowups, and scores of rave reviews from all regions of the country. And yes, that too made it into the show!

Fans thirsting over Chris Colfer's sexy new muscles for Coachella