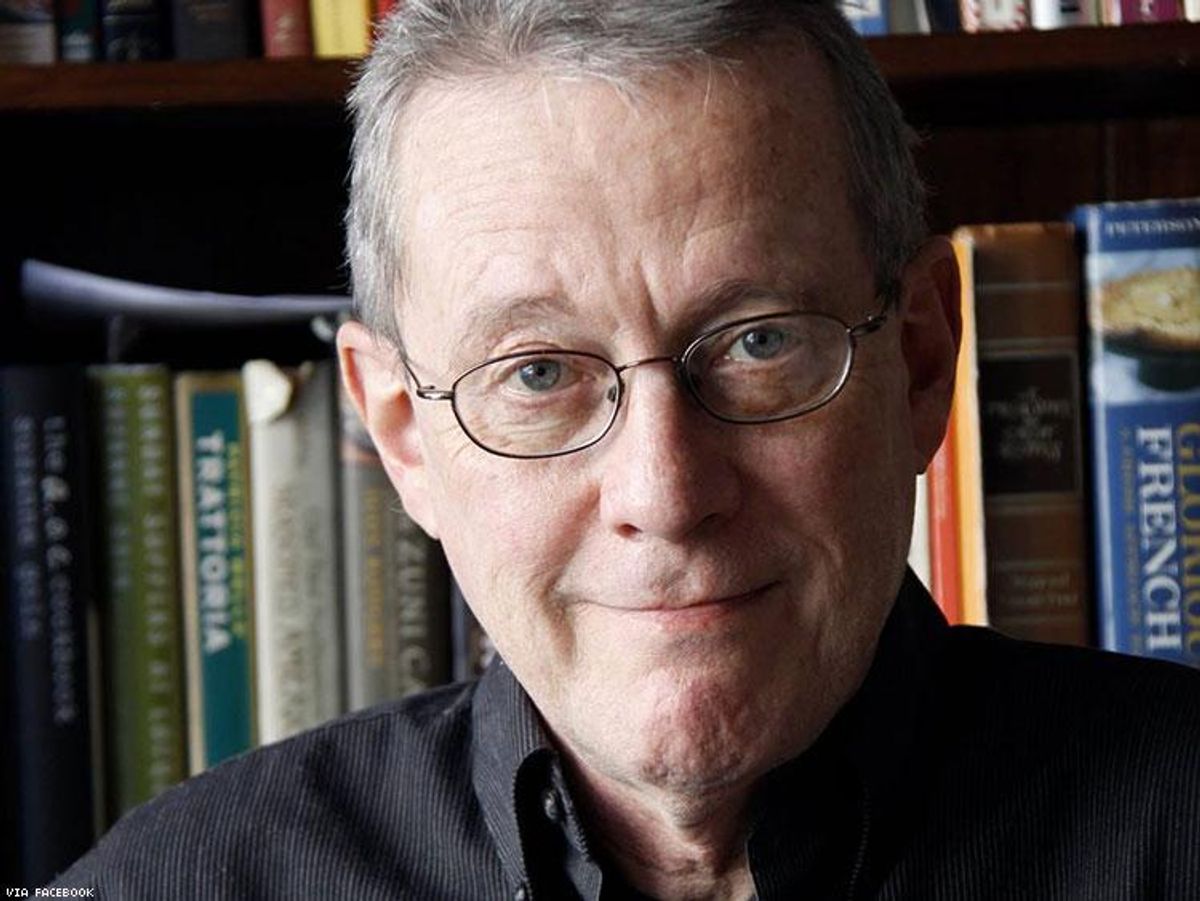

Mark Merlis was one of our finest writers -- and by "our" I mean not just gay, but American. He wrote four magnificent novels that explore American life with the insight and power of the best work of James Baldwin and Philip Roth. I was his friend, but I met Mark through his books and know him best through his books. He was a true artist.

He died August 15 at Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. A year ago he was diagnosed with ALS, the degenerative nerve disease also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. He went into the hospital August 10 with pneumonia. As his husband, Bob Ashe, said in his public announcement, "He wanted his intubation tubes removed for a peaceful journey." Bob added, "He died as he lived ... on his terms." He was 67.

Mark was only two years older than me, but seemed to belong to an older, more sophisticated generation. He drank scotch at a time when it had not yet returned to fashion. His literary heroes were all from the 1940s and 1950s -- this made him an excellent interpreter of pre-Stonewall lives for post-Stonewall readers. He was a man in love with the past.

His first novel, American Studies, is narrated by an older gay man laid up in a hospital bed after being gay-bashed. He remembers his strange, sad, confusing affair with a famous literary professor who died mysteriously during the postwar Red Scare. Mark's fourth and last novel, JD, is narrated by the wife of a long-dead New York polemicist from the Vietnam era. Her account is twined around the journals her gay husband left behind, an ingenious double helix of storytelling that twists deep into sexual and political history.

His books share a family resemblance: fine literary texture, a keen sense of gay history, a moral complexity worthy of Henry James, and strong sexuality. But he never repeated himself. His second novel, An Arrow's Flight, my personal favorite, begins as a stunt, an elaborate joke: a gay retelling of the Philoctetes story set in the age of AIDS. Go-go boys mingle with Greek soldiers in ancient armor; soothsayers advise hustlers. It's wonderfully inventive and wildly funny. Yet the novel ends on a tender note that's not just moving but wise.

Mark grew up in Baltimore, the son of a Jewish doctor and a Catholic mother. He earned a bachelor's degree from Wesleyan and a master's in American civilization at Brown. He met Bob in a bar in Baltimore in 1982. Bob is African-American and worked for Johnson & Johnson, eventually becoming an executive there. Mark once joked that Bob's family liked Mark better than they liked Bob, and that he liked Bob's family better than he liked his own. But Mark was actually close to his two brothers.

He was a writer with a second full-time career, health care analysis, first with the Library of Congress and later as an independent consultant. I remember looking him up on a university catalog system back in 1999 and being startled to see so many titles under his name. At this point he'd published only two novels. But the other titles were all papers and pamphlets about federal health care policy. He gave this professional experience to the protagonist of Man About Town, his third book, the closest he ever came to an autobiographical novel, the comic, wistful story of a middle-aged gay man hunting down a male bathing suit model from the magazine ad that obsessed him as a boy.

Mark was able to sustain his two careers simultaneously thanks to his ability to wake up early and write for one or two hours every morning before he went to work. This meant that progress on each book was slow but steady. His books are beautifully planned and solidly structured. He was able to keep this up for years.

An inveterate grumbler, often a witty one, he did not suffer fools gladly. Since he was very smart, he could not help seeing the rest of us as fools at one time or another. This often rebounded and he saw himself as a fool too. He could be intensely self-critical. I remember a conversation with him and fellow writer William Walker when Mark dismissed Man About Town as a bad book. William and I stared in disbelief. William spoke first. "I love that book." I added, "I do too." Mark grumbled, "Well, you must be the only people who think that way."

He never found the audience he deserved -- few novelists do -- but he was deeply admired by his peers and by serious readers. He was praised in print by Richard Howard, Paul Russell, Richard Wilbur, Scott Heim, and Michael Bronski. When he died, Facebook was full of readers telling each other how much they loved his work.

Mark and I were friends, but I often felt I knew his books better than I knew him. We didn't live in the same city. He lived first in Washington, D.C., then in New Hope, Pa., and finally in Philadelphia. He came to New York now and then and we often got together. He never lost the ability to surprise me. After an early visit, he bid me good night to go to a piano bar, Marie's Crisis, to listen to show tunes. Earlier this year, he told friends he was selling his piano. He couldn't play it anymore because of his ALS. This was the first time I ever heard that Mark played the piano.

He might be called the American Alan Hollinghurst -- both novelists are highly literary and fearlessly sexual. But I think there is more emotional drama and meaning in Mark's fiction, more weight and depth. He was an extraordinary, gifted writer. He will be greatly missed.

CHRISTOPHER BRAM is the author of Gods and Monsters and Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America.